drawing, print, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

ink

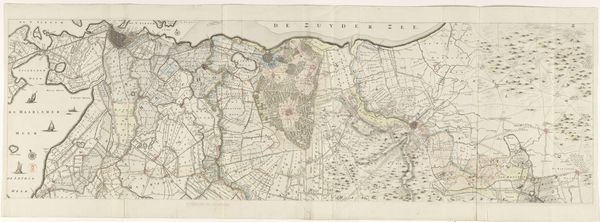

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 1856 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

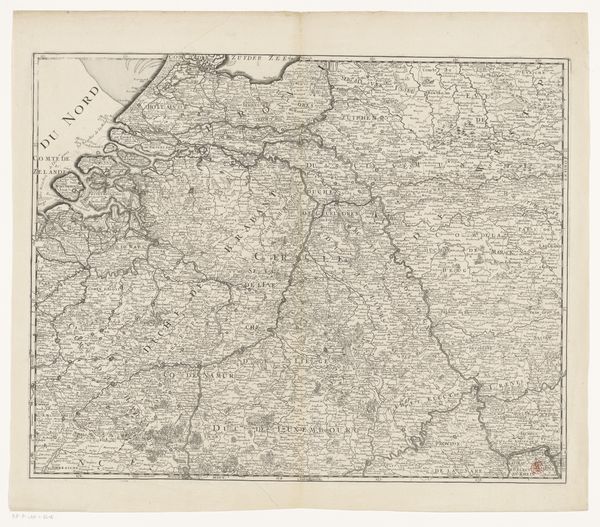

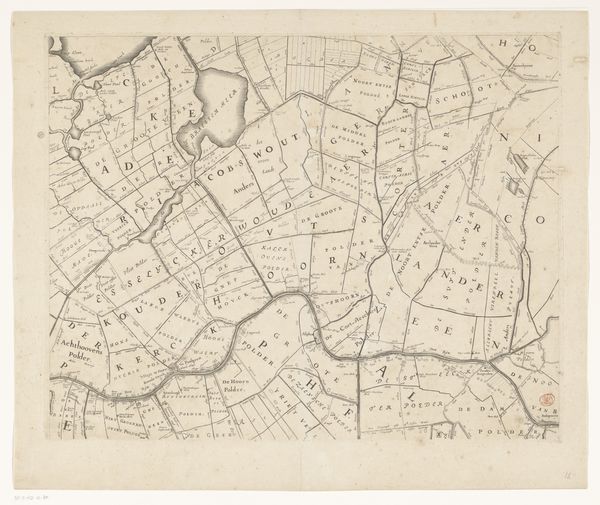

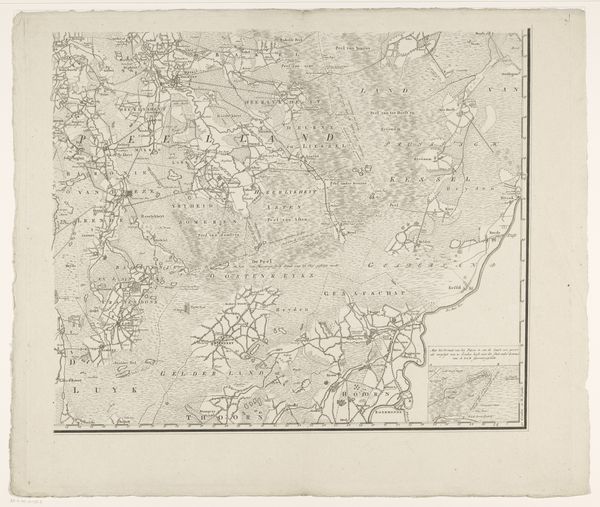

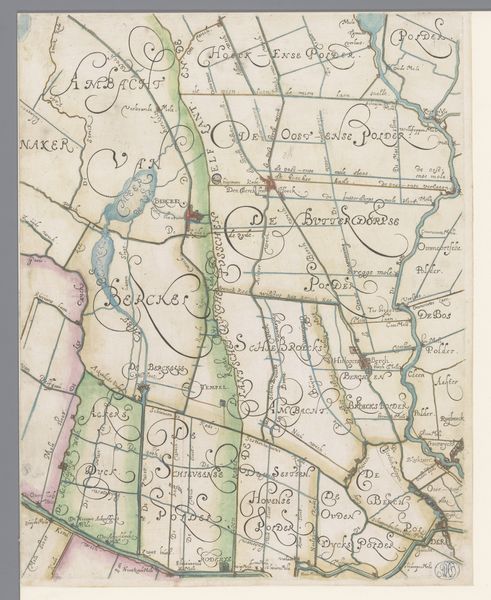

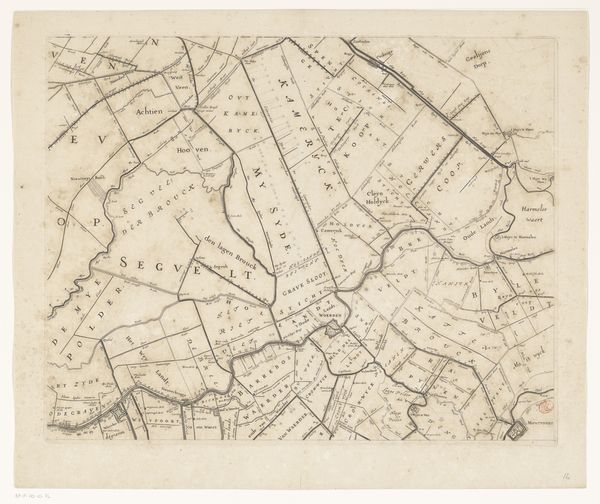

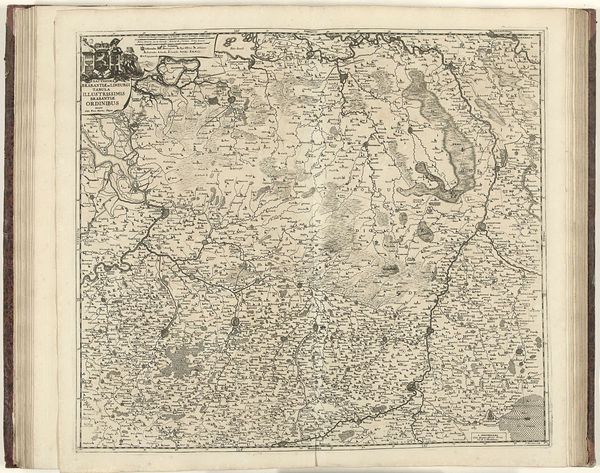

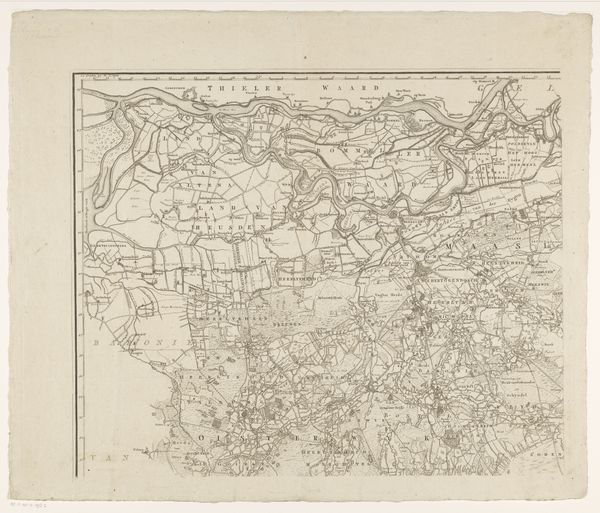

Curator: Let's delve into this "Kaart van de provincie Utrecht (onderste deel)"—a fascinating map of the province of Utrecht. Created sometime between 1696 and 1743, it offers a glimpse into the cartographic landscape of the early modern period. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the sheer precision of the lines. There's such control and order in depicting the landscape; it really conveys a sense of power and ownership over the territory. It is meticulously drawn and etched. Curator: Absolutely. Maps in this era were instruments of power. They were not merely descriptive, but also performative. The map would define territories and therefore claim control. What do you think about the relationship between space, knowledge and gender regarding this map? Editor: Maps as knowledge production centers during the Dutch Golden Age have deep, although complex, relations with coloniality. As these territories were explored, mapped, and visually cataloged, Indigenous place-making was dismissed and therefore erased from this visual and intellectual register. There's an inherently patriarchal element, isn't there, in claiming to "know" and "name" a land? In many cultures, place is inherently feminized through notions of belonging, heritage, and genealogy. These baroque cartographies were used to disrupt that symbolic sense of space. Curator: Precisely. Also the relationship with water should be regarded, given the fact that this province has gone through important hydraulic engineering. What is implied through mapping a geography whose characteristics depended on such infrastructure? Editor: That's an astute point. It highlights how Baroque landscape rendering goes beyond mere objective documentation to emphasize an active, constructed version of control over nature itself. This extends beyond simply the physical infrastructure of canals to the symbolic infrastructures of power projected onto that landscape. In a society so critically intertwined with water management, a map serves not just as spatial representation but also as an assertion of collective capabilities, technological dominance and social harmony. Curator: It makes you wonder about who was considered 'mappable' at that time, doesn’t it? How the dominant culture defined who gets a place on the map—both literally and figuratively. Editor: It’s a potent reminder of the exclusionary practices woven into the fabric of seemingly neutral or 'objective' historical documents. These prints offer complex intersectional investigations regarding geography and knowledge production during that period. They are definitely documents we must reconsider within post-colonial approaches to history and art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.