print, photography

#

aged paper

#

script typography

# print

#

sketch book

#

hand drawn type

#

landscape

#

hand lettering

#

river

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

orientalism

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 32 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

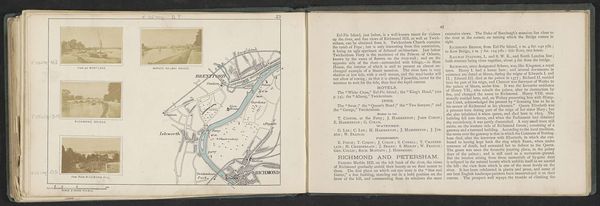

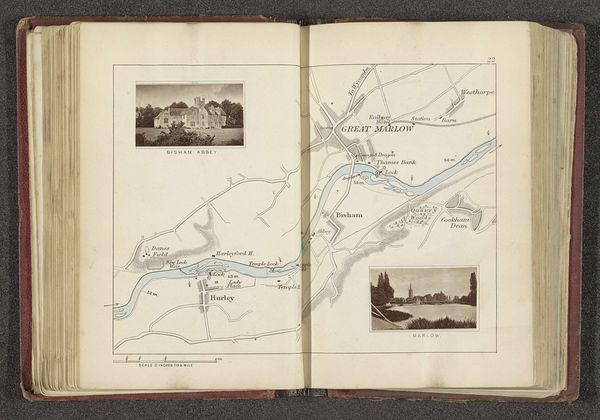

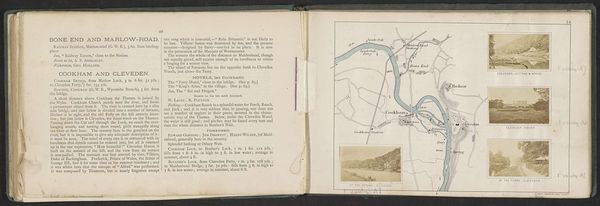

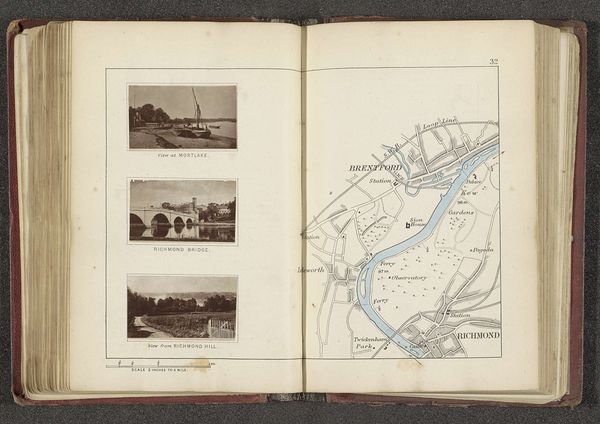

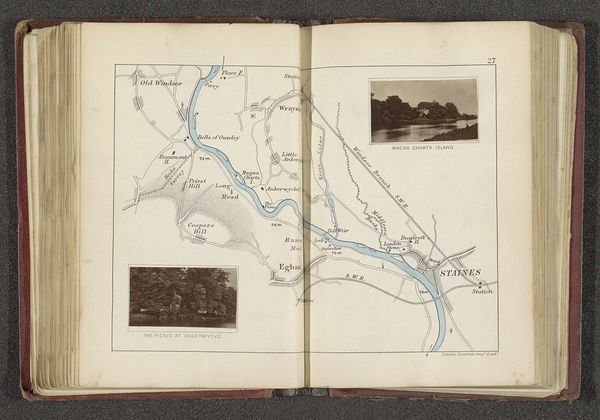

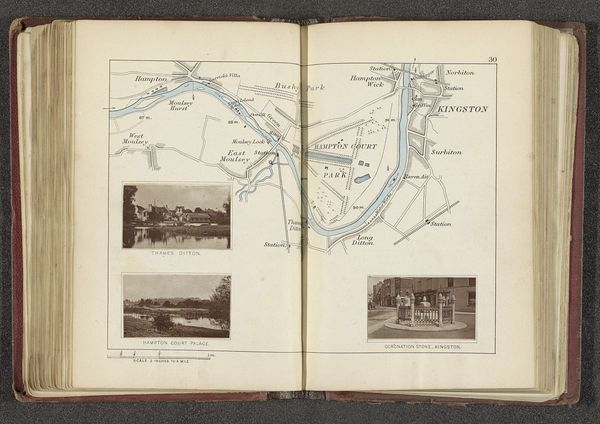

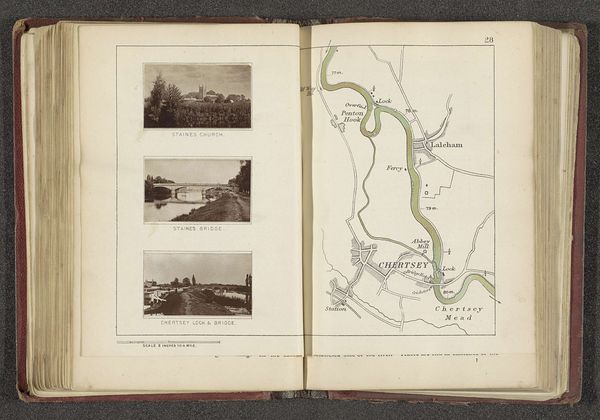

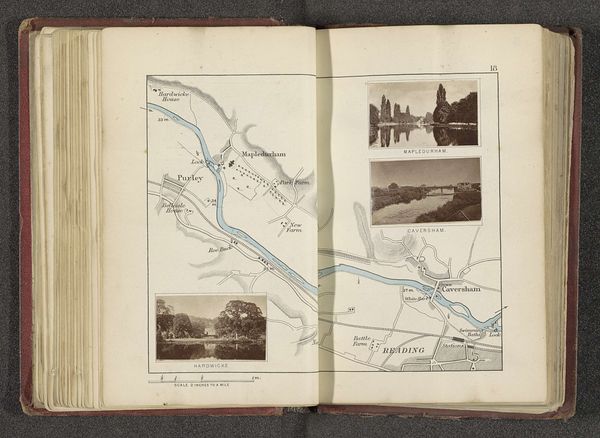

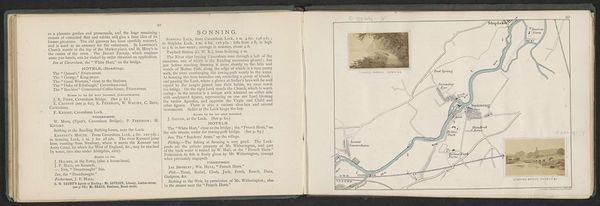

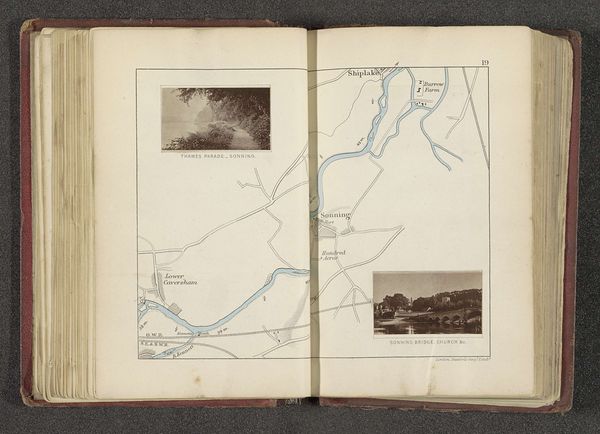

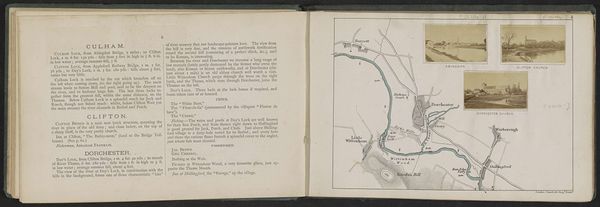

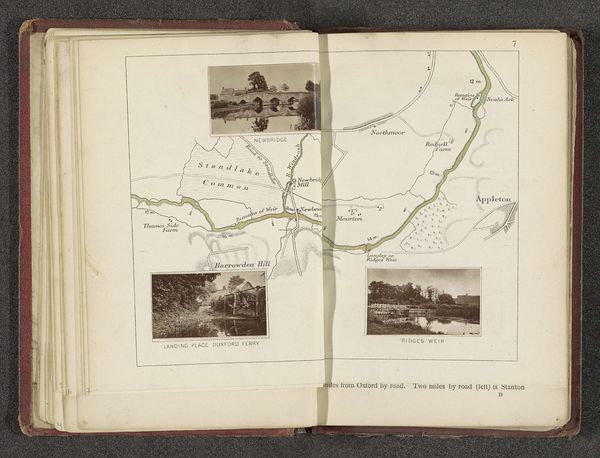

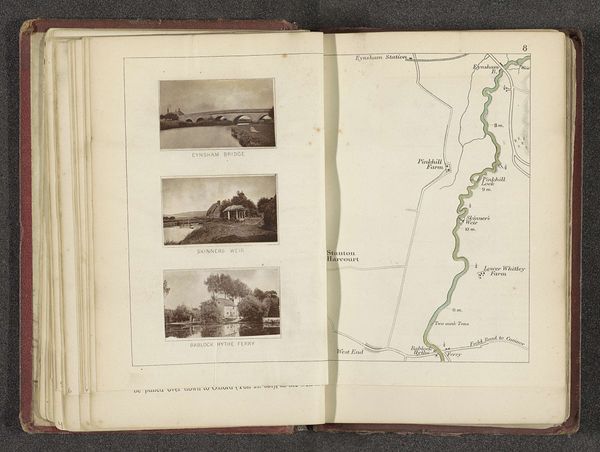

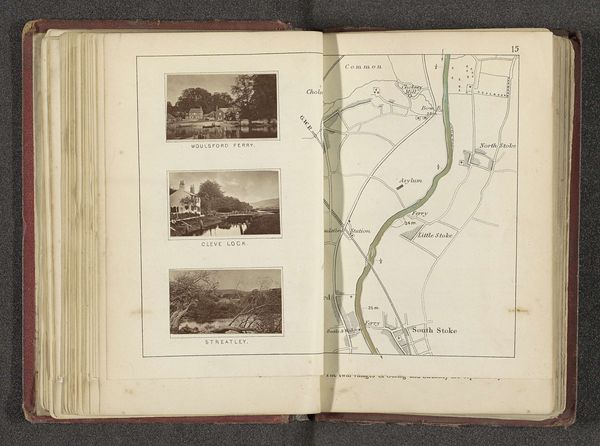

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this intriguing page from a sketchbook, entitled "Gezicht op Hardwicke," dating back to 1871, by Henry W. Taunt. It seems to be a blend of photography and cartography, reproduced as a print. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by its almost wistful, fragmented nature. It’s a study in contrasts – rigid lines of the map against the softer edges of the photographic insets. The whole composition has a sense of a journey, both physical and perhaps emotional, preserved within the pages of this book. Curator: That sense of a journey is quite apt. Notice the detail given to the course of the river, the deliberate charting. It reminds me how integral landscape, and its representation, was to Victorian conceptions of order and control, achieved through techniques marrying the artistic and the scientific. Editor: Absolutely. And considering the broader social landscape of 1871, with burgeoning industrialization, a piece like this becomes a poignant reflection on the changing relationship between humanity and the natural world. Were these landscapes also sites of leisure or labor? Were they contested spaces? I want to know the indigenous histories layered within and suppressed by these aesthetic frames. Curator: I think your approach is a bit misleading in this context, as it asks a drawing to do the work of an historical document. The precision of the river's rendering, the calculated placements of photographic vignettes–aren't these testaments to the artistic method of capturing essence? Consider also the handwritten typeface at the bottom. It suggests a personalized approach to preservation, a unique intersection of technical drawing and sentimental memory. Editor: Perhaps. Yet, to separate this "sentimental memory" from its socio-political context feels irresponsible. How did colonial powers and systems of oppression affect what landscapes were memorialized? Curator: But regardless, the drawing, as a visual artifact, is the place to begin a visual analysis of landscape, identity, and colonial history. Editor: An important reminder to stay grounded in visual detail, even when expanding the context. Thanks, Curator, for that focus. Curator: Likewise, Editor, your ability to bring this history back into a drawing is always revelatory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.