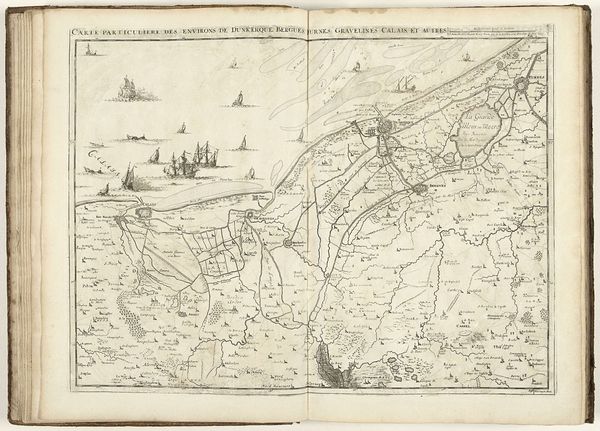

print, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 430 mm, width 570 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

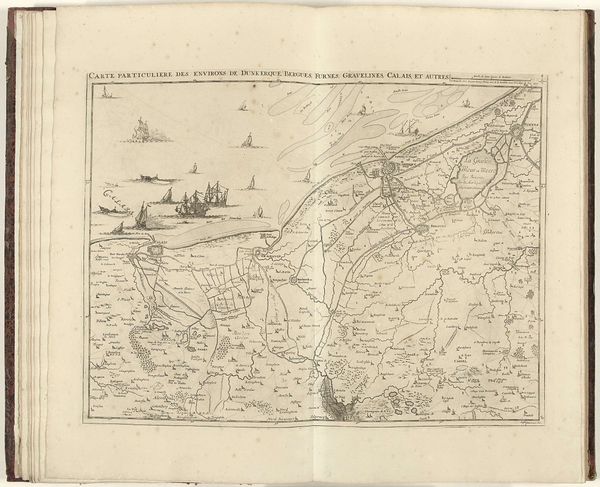

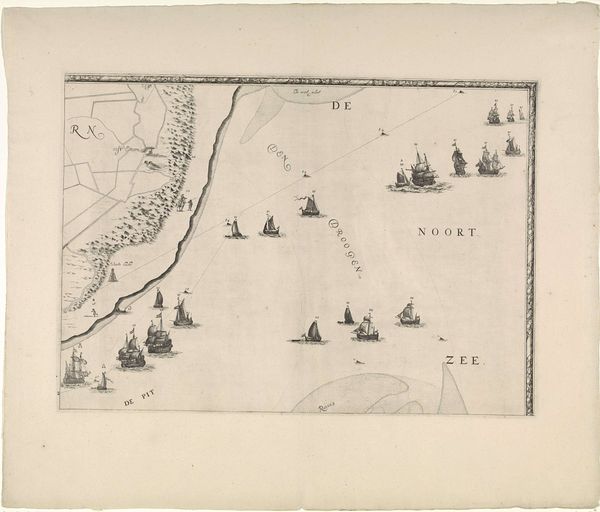

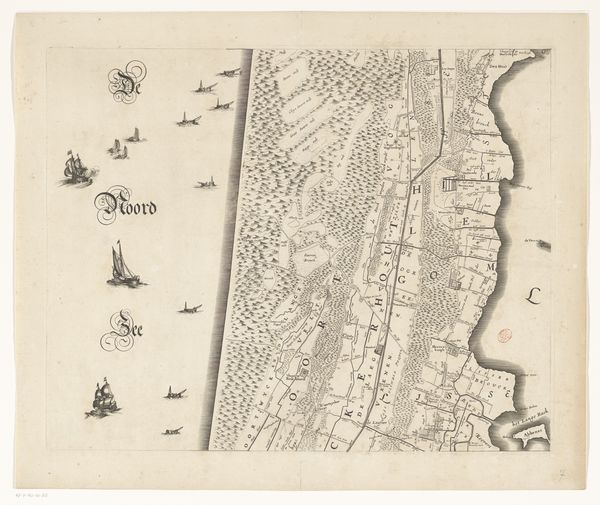

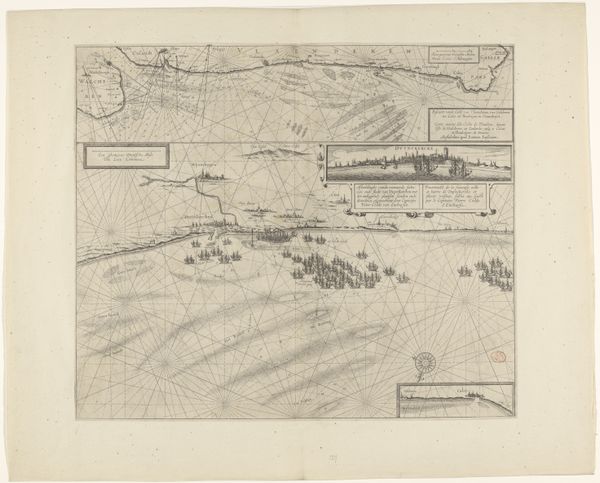

Curator: Before us, we have a map—"Kaart van West-Vlaanderen, 1707"—created in 1707 by Jacobus Harrewijn. It is currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, the precision of the lines strikes me. There's a stillness, a sort of poised expectation in this depiction of land and sea. Curator: Well, this particular map provides insight into the historical cartography of West Flanders during a significant period of political and economic change. It’s more than a simple record; it reflects power dynamics and how the landscape was understood. Editor: Exactly! Think of the labor and skill needed to produce an engraving like this. The very act of mapping—of defining territory and boundaries—it’s a forceful statement about control. And note the ship: materials transported to be consumed abroad. Curator: Absolutely. Maps aren't neutral; they're cultural documents shaped by societal agendas. We need to unpack the layers of meaning imbued in this seemingly straightforward landscape. It tells us so much about spatial awareness, economic ambition, even nascent notions of national identity. How West Flanders defined its borders during ongoing conflict. Editor: And the uniformity of the rendering. Everything feels rendered with the same importance; no visual hierarchy to focus our eye on. In the composition, the evenness, what’s elevated? Is there a focus of materiality in a region that creates and ships abroad? Curator: An astute observation. Considering the gendered lens of mapmaking as inherently masculine—plotting and controlling the ‘feminine’ land—we have to confront who gets to define and interpret this space. Editor: Fascinating, to view the means of production within such clear artistry of Dutch influence in 1707. Curator: Yes, and I think exploring the cultural context is just as critical to understanding maps like this, considering colonial expansion and other narratives during the period. The print serves as a touchstone for discussing history, identity, and how art plays an integral part. Editor: The dialogue it provokes makes the act of its making all the richer, truly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.