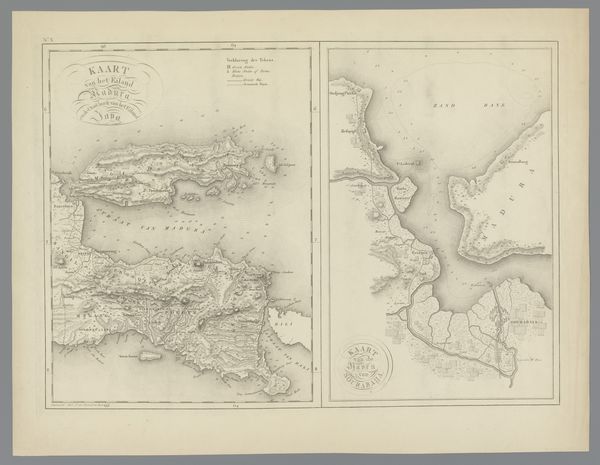

print, engraving

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

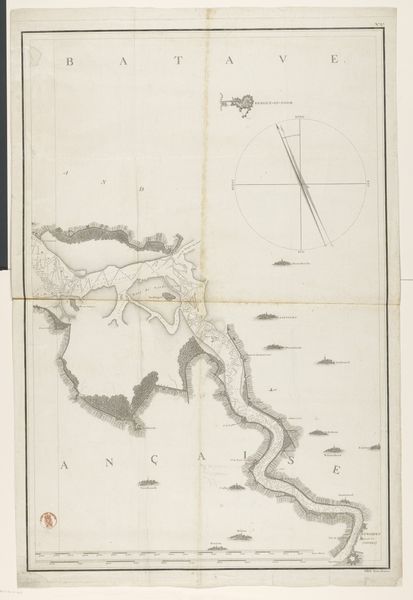

Dimensions: height 385 mm, width 476 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

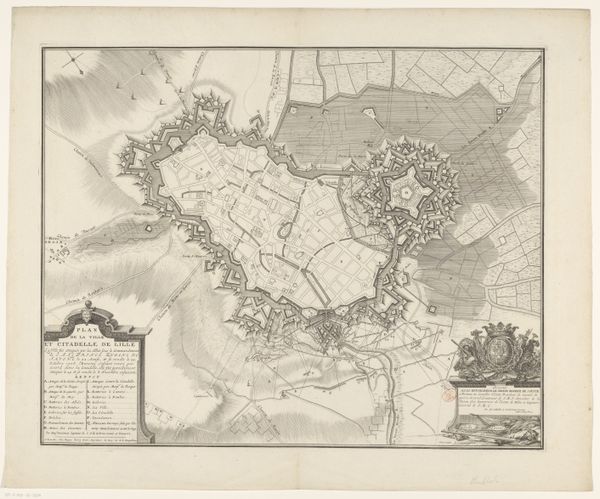

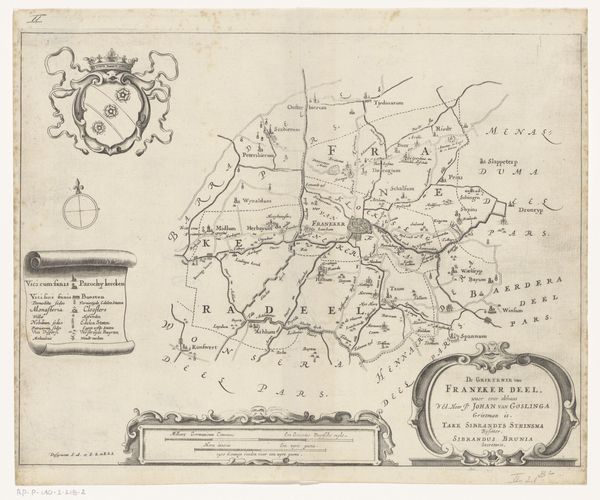

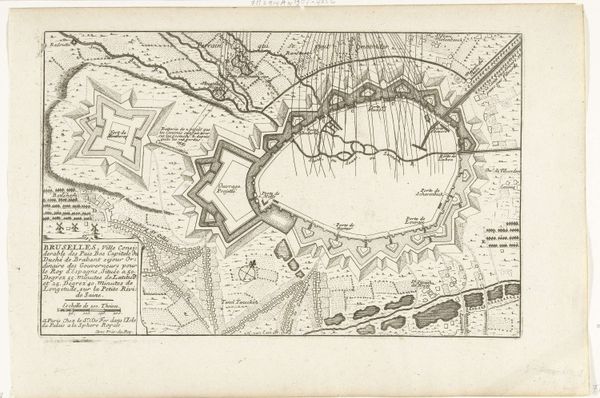

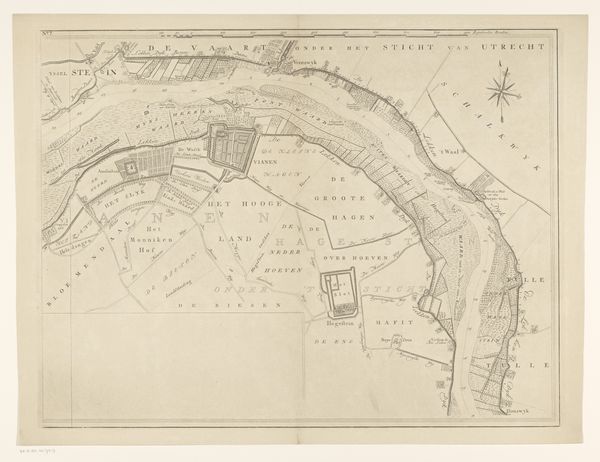

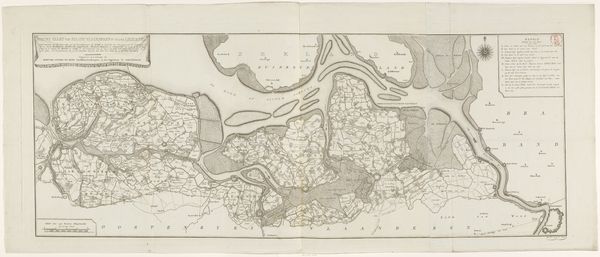

Curator: Here we have a print entitled "Kaart van Java met een plattegrond van Batavia," or "Map of Java with a Plan of Batavia," created in 1816 by C. van Baarsel en Zoon. It is an engraving on paper. Editor: The detail is incredible. It reminds me of an intricate lace doily laid out on a dusty old table. I can almost smell the parchment and ink. There's a strange sense of... dominion to it, of claiming territory. Curator: Exactly. Maps are not just about geography; they're laden with cultural and political meaning. This one presents Java, then a Dutch colony, with Batavia, now Jakarta, prominently featured. The inset, that plattegrond, underscores the significance of that particular urban space within the larger colonial project. We are invited to observe from above, claiming an illusory mastery. Editor: It's that ‘birds eye view’ feeling that triggers me. A kind of disembodied perspective where everything looks so neat and ordered from afar, devoid of the chaotic mess of real lives lived. Does that make sense? It also strikes me, how cartography and power seem intertwined, right? Curator: Absolutely. This isn’t a neutral representation of the island. It reflects European modes of seeing, organizing, and, yes, controlling the landscape. Think about how names are inscribed; decisions were made about what to highlight. These are acts of power, reinforcing colonial narratives. The orientation alone could affect cultural perception and interpretation. Editor: And the level of precision in the engraving suggests meticulous surveying, not just of the land but, indirectly, of resources and people too, I suppose? Like marking assets on a grand chessboard. I’m reminded of old trade routes crisscrossing the globe, shaping not just economies, but also cultural identities, hybrid realities. Curator: Precisely. The print provides invaluable historical data while revealing that seemingly ‘objective’ maps served clear ideological purposes. By examining how places are represented we uncover buried assumptions about space, culture, and power relations. Editor: It prompts you to consider the untold stories lurking beneath its crisp lines. Colonial ventures weren’t all top-down planning; individual experiences would have differed greatly. Still, you have to concede this is a beautiful piece, if aesthetically imposing and faintly chilling in its implications. Curator: Indeed, it presents a compelling lens through which we can consider the intricate, often unsettling, connections between spatial representation and the exercise of colonial authority. Thank you for your perspective, Editor: And thank you, I found that really insightful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.