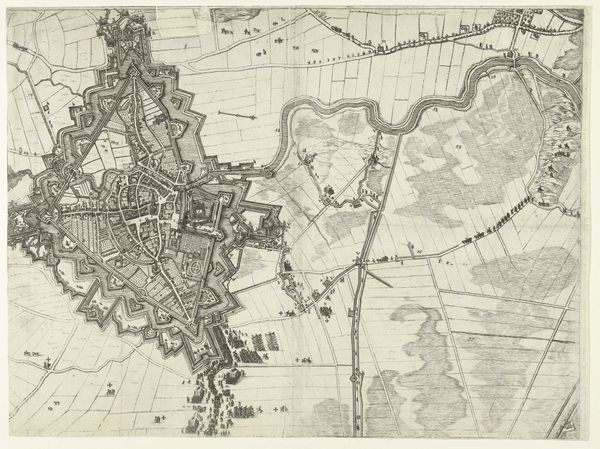

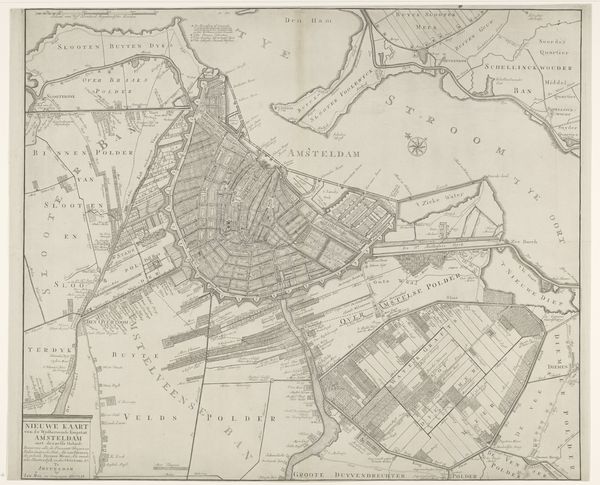

drawing, print

#

drawing

#

aged paper

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

natural palette

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 983 mm, width 382 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

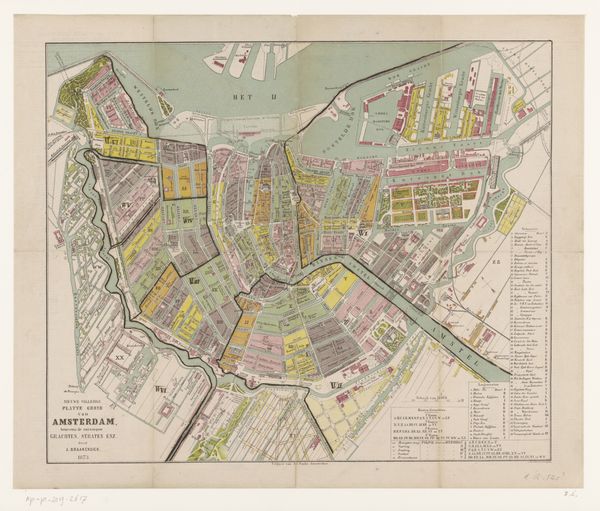

Curator: Here we have "Plattegrond van de stad Batavia," a city map created by G.P.F. Cronenberg in 1866, held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. It's rendered in what appears to be print and drawing techniques, perhaps with watercolor washes. Editor: My first impression is of an incredibly detailed and precise document, but also one that feels somewhat melancholic. The muted colors and aged paper lend a sense of distance and loss, a longing for a Batavia that perhaps no longer exists. Curator: Absolutely. Maps, of course, are never simply neutral documents. They are deeply embedded with power, in this instance reflecting Dutch colonial influence and control over what is now Jakarta. Consider the careful delineation of the city’s infrastructure: canals, fortifications, administrative boundaries… All speak to systems of governance. Editor: It's interesting how the natural landscape surrounding the city is also carefully rendered. The lush greens and blues almost romanticize the environment, while the tightly gridded urban spaces speak to imposed order and hierarchy. You feel the tension between colonizer and colonized, the human-imposed city struggling against the surrounding natural abundance. Curator: Yes, that dichotomy is essential to understanding colonial visuality. Consider the visual cues. The indigenous spaces would have possessed other signifiers – maybe symbols or forms or artistic approaches that might represent freedom from that enforced order, something lost in translation, or worse suppressed. Editor: The inclusion of legends and keys invites a reading of Batavia not merely as a geographical space, but as an organized societal structure. But how accurate is that structure? Whose perspective is reflected here? It’s the selective truth of the colonizer being visualized, of course, a tool of claiming ownership, shaping narratives, justifying dominance. Curator: It asks us to look at historical power structures with their marks on both people and place. So, it functions, after all this time, as a critical prompt, one layer visible above many others that have faded but can, potentially, still be found, in other ways. Editor: Precisely. It serves as a poignant reminder that what we see is never the full story, inviting us to consider the unspoken narratives, the perspectives often absent in these historical documents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.