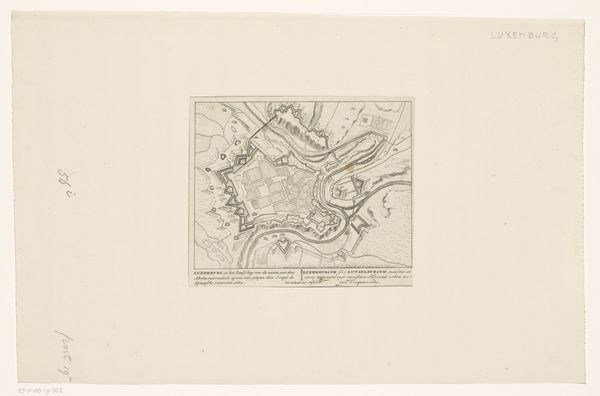

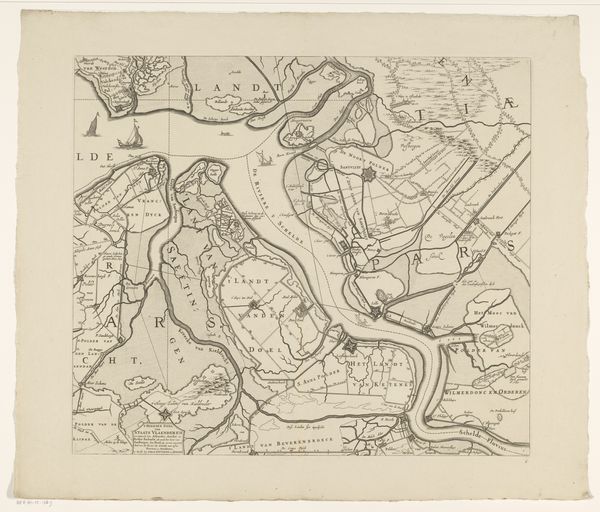

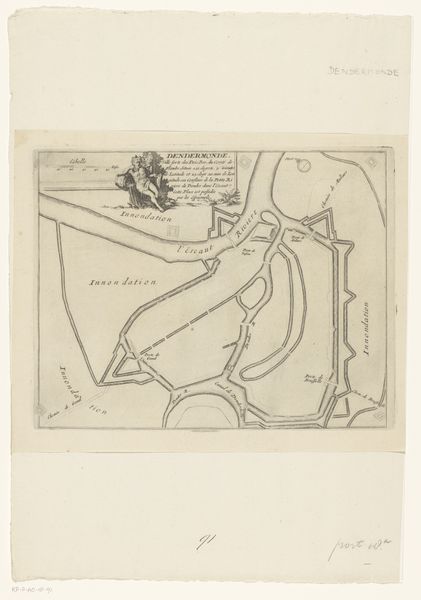

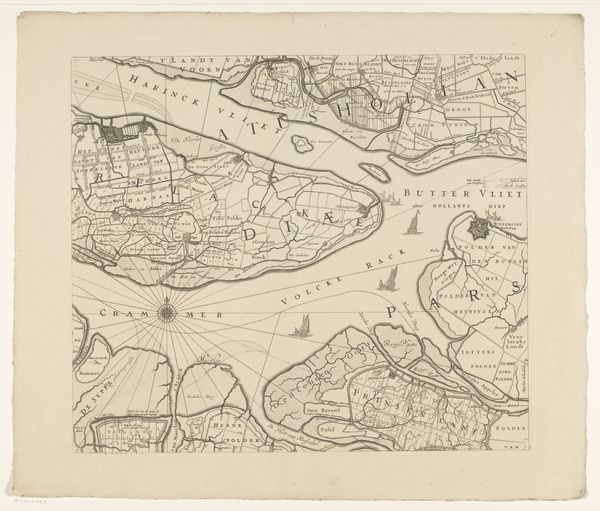

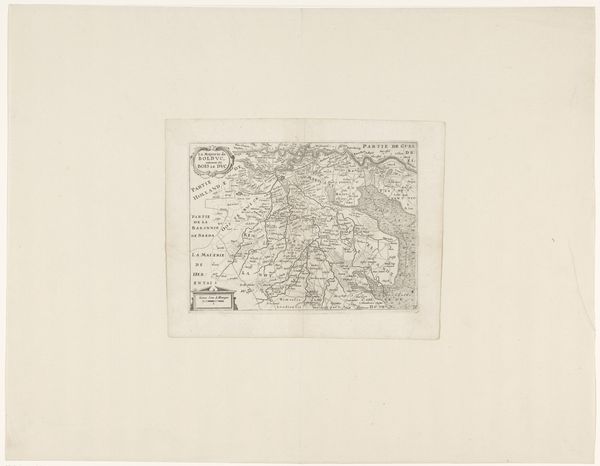

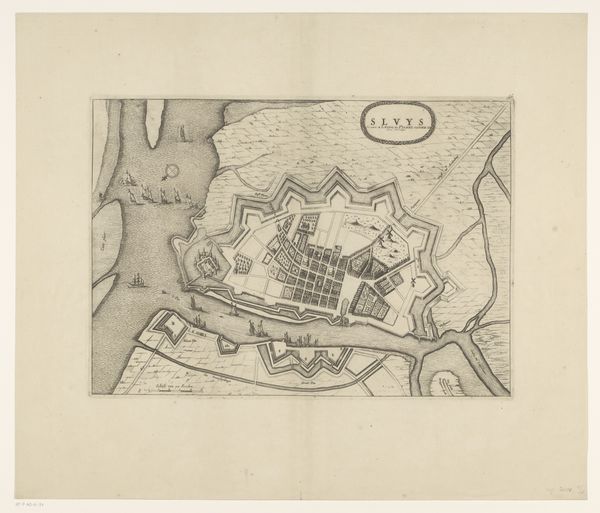

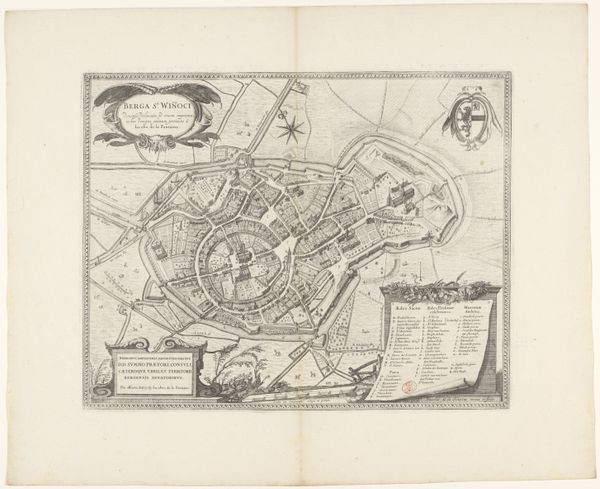

Kaart met beleg en verovering van Schenkenschans door Frederik Hendrik, 1635-1636 1651

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

print, etching

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

Dimensions: height 277 mm, width 364 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this intricate print, the "Kaart met beleg en verovering van Schenkenschans door Frederik Hendrik, 1635-1636," etched in 1651 by an anonymous artist, my first thought is how incredibly detailed and organized it appears. Editor: Yes, the precision is striking. It feels simultaneously objective and charged with political intent. All those careful lines speak volumes about power, territoriality, and military strategy during the Dutch Golden Age. Curator: Exactly. What this landscape shows us is the visual language used to define possession during the 17th century. Consider how it depicts not just geography but also the implications of war and siege. What are we seeing here? Editor: We're presented with more than just a simple landscape. The piece focuses specifically on the siege of Schenkenschans by Frederik Hendrik in the years 1635 and 1636. There's a detached quality, a sense of removed overview... which reminds me how those in power frequently depersonalize conflict through representation. Curator: Right, it almost transforms the chaos and violence into a palatable and digestible "historical event". Who wins or loses here? Does a 'neutral' landscape even exist within conflicts of war? What assumptions of power relations, of center and periphery, do such representations carry with them? Editor: Also, in studying prints like these we uncover much about the society in which it circulated. How many of these images were produced and disseminated, for instance, among the public and for what specific ends? Were they primarily tools of nationalistic propaganda? What audiences are able to actually read and consume images like this? Curator: Absolutely, these were images constructed to inform, but also, I'd wager, to impress and inspire. Understanding art from this period as a propaganda tool gives us insight into the ways conflict was 'sold' to the public, solidifying particular political narratives. Editor: Indeed. It urges us to confront the relationship between artistic creation and the political landscapes of its time. So next time you look at landscape, question whether it exists free from bias and power. Curator: It leaves me thinking about how art, even in seemingly documentary forms like map-making, actively participates in shaping the collective memory and justifying particular histories. It is imperative we adopt an intersectional narrative that questions everything at face value.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.