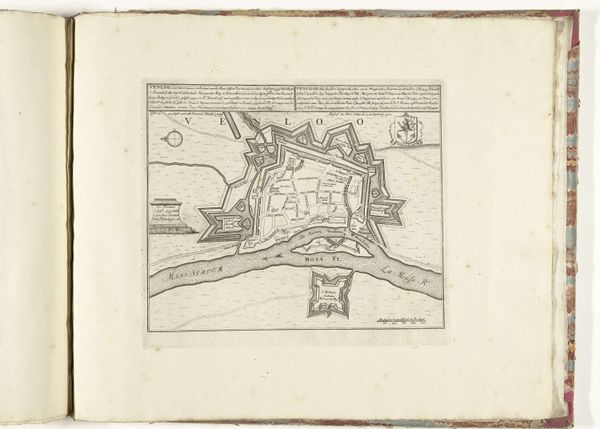

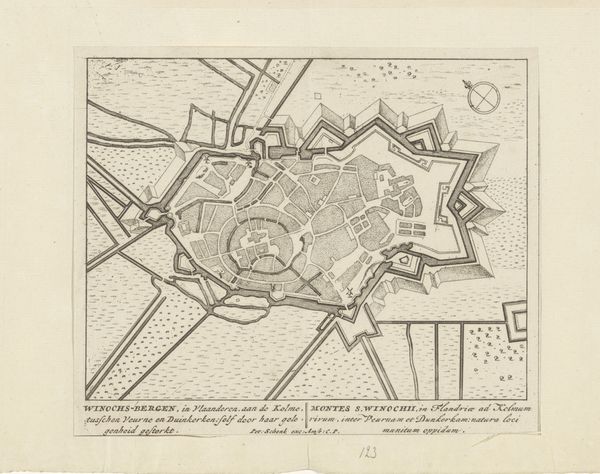

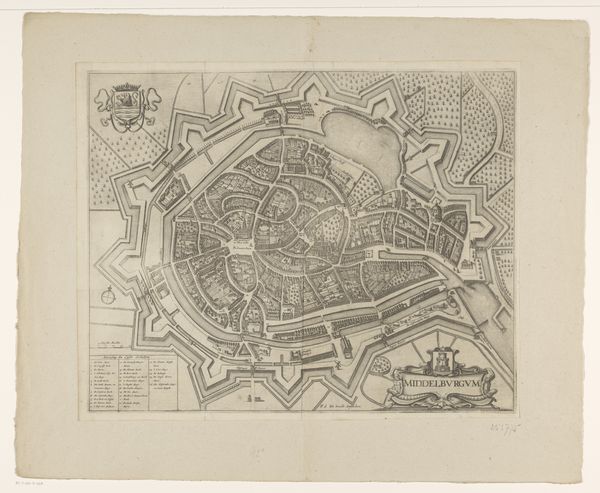

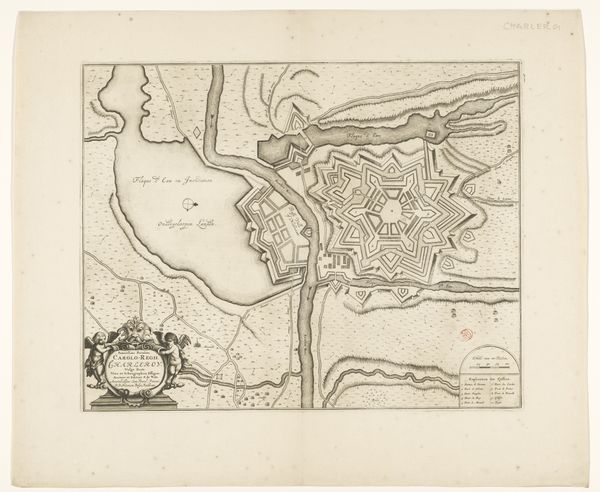

print, ink, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

ink

#

geometric

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 392 mm, width 492 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Jacobus de la Fontaine’s "Plattegrond van Sint-Winoksbergen," an engraving made with ink, dating back to 1652. What strikes you most when you first see it? Editor: It has this beautiful, almost clockwork precision about it. All the components seem painstakingly plotted, revealing the hand in production. It feels more like an instrument than an image, perhaps. Curator: Indeed, its function as a representational tool can't be ignored. But, thinking about that function, how do maps construct narratives of power and place? What's emphasized here, and what gets left out? Editor: The clear delineation of urban space highlights controlled expansion. Notice the way the outer defenses constrict movement, regulating labor and production that supports urban centers and commerce. There's very little given to the natural world, beyond functional features. Curator: Absolutely. The cityscape theme speaks volumes. We must also recognize this baroque piece as part of a specific European colonial and mercantile context. What stories are being told – or obscured - through the act of mapping a space in this way during this era? Whose perspectives are privileged in such cartography? Editor: It suggests that mapping served specific needs; to assert ownership, control movement and commodities, the military use of the engraving must also be addressed. Think about who likely accessed these images. The print process is crucial here—it allows for dissemination among the political and economic elites of the period. Curator: Precisely, print production served those interested in both commerce and exerting regional power. How does considering the role of class and power influence our interpretation of the artwork itself? Can we interpret its detailed aesthetic as a political or even a colonizing act? Editor: I hadn't considered it from that perspective. Viewing the rigid geometry not simply as a form of craftsmanship but a function of that power shifts the reading dramatically. Curator: It certainly reframes how we might think of city planning as a system for the distribution of resources as much as just aesthetic design. Editor: Yes, acknowledging how production, material and its place, even here in something as "simple" as an architectural plan—changes the way you read an image. It emphasizes human action in defining lived space.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.