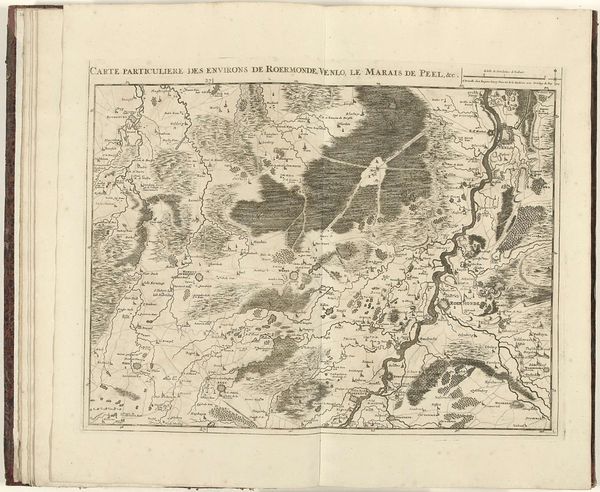

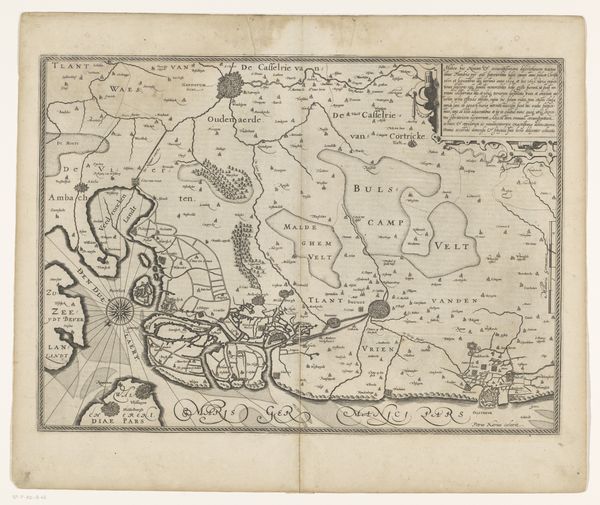

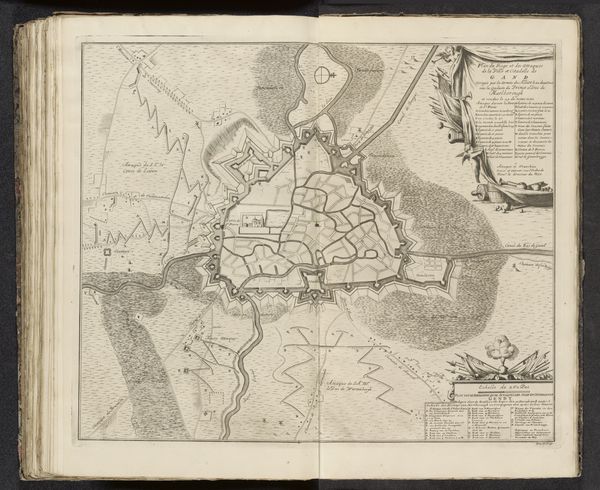

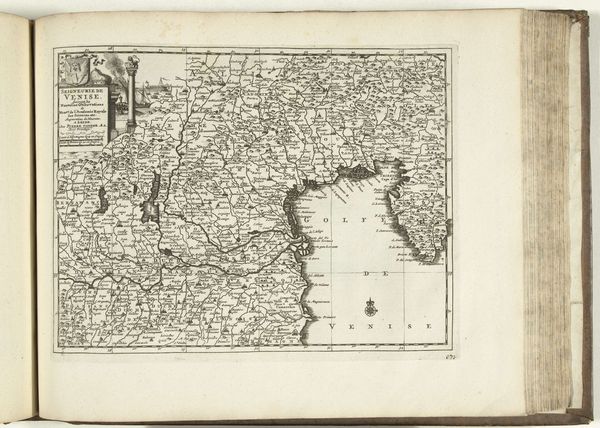

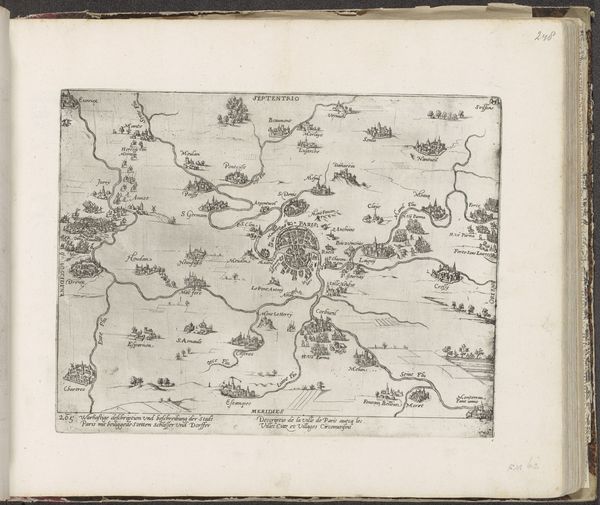

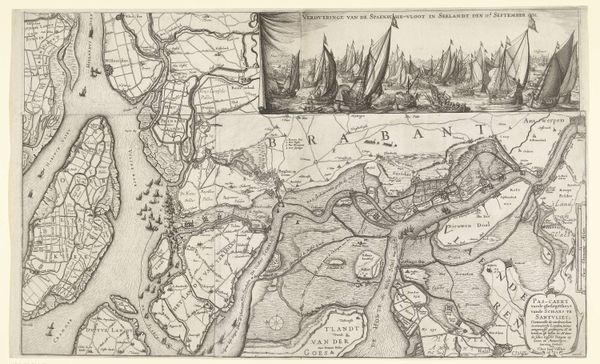

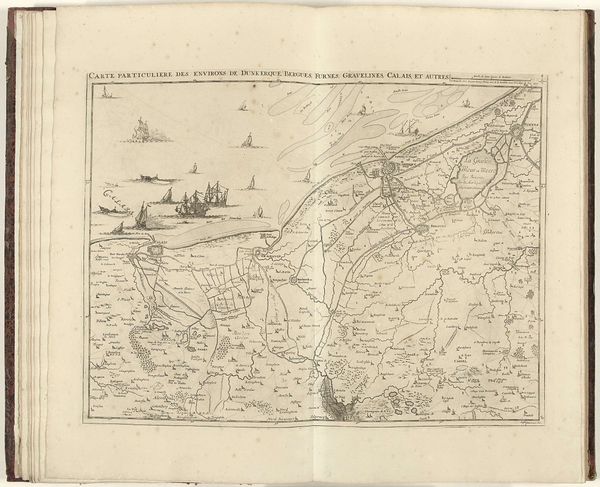

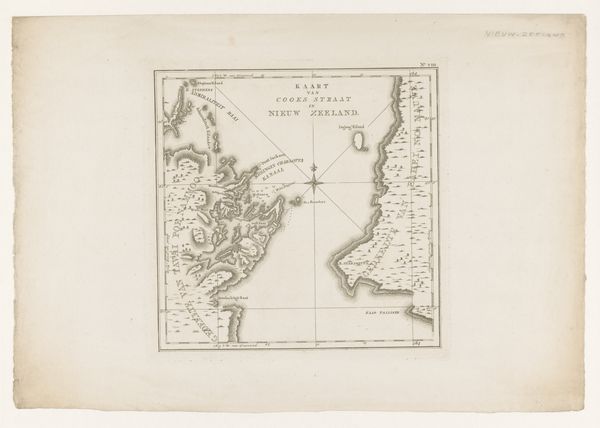

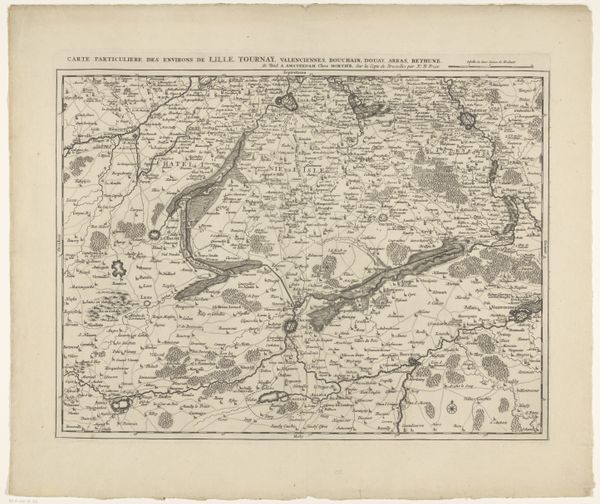

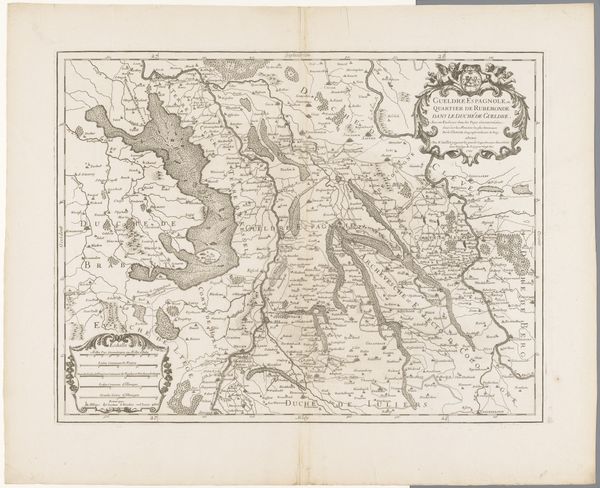

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen and pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

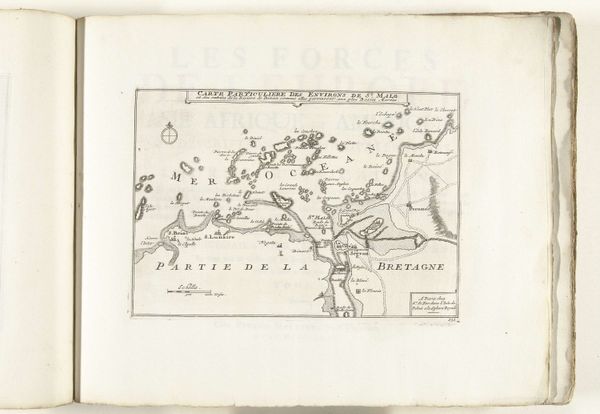

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 276 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at a map titled "Kaart van de kust bij Brest, 1726," an engraving by an anonymous artist held in the Rijksmuseum. What strikes you about it? Editor: The delicate linework! It’s surprisingly expressive given that it's a map intended for navigational utility. There's an aged quality too, the toned paper lends a melancholic air, as if whispering stories of long voyages and lost sailors. Curator: Absolutely. Consider how maps in the 18th century weren’t just about geographical accuracy, they also communicated power and knowledge. Cartography was deeply implicated in colonial projects, establishing claims over territory and resources. Brest was a strategic port. Editor: It's fascinating how the symbols and imagery are designed. That ornate cartouche with the sailing ship—it's not merely decorative, it speaks of naval might, of trade routes, of exploration and conquest, a visual shorthand for France's maritime ambitions. Curator: Exactly! The map encodes hierarchies. Notice the level of detail given to the coastline versus the more generalized inland areas. This prioritizes naval perspective, literally marginalizing indigenous experience and local knowledge. Editor: It almost feels like a theater set—this coastal scene as a stage for human dramas, particularly male ones. The ocean is rendered as opportunity. What do you think it elides when thinking about gender? Curator: That’s astute. Gendered dimensions often go unexamined. While seemingly "objective," it actively participates in shaping a world seen and experienced through very particular power dynamics. The map can give the sense of charting the destiny of people based on trade and colonial activities. Editor: I do love the almost organic shapes describing the inlets and bays. The map’s beauty, if you allow me to say so, arises from what is visually articulated beyond functionality and utility—memory, dreams, history, conquest all swirl around Brest's shoreline in 1726. Curator: Agreed. Appreciating it today involves questioning its original purpose. It should make us reflect upon the map-making itself: what perspectives does it validate, whose voices are missing, and how its imagery perpetuates certain narratives, specifically French colonial ones, and erases others? Editor: So well said, bringing historical awareness makes for new layers of appreciation. Thanks! Curator: You as well! Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.