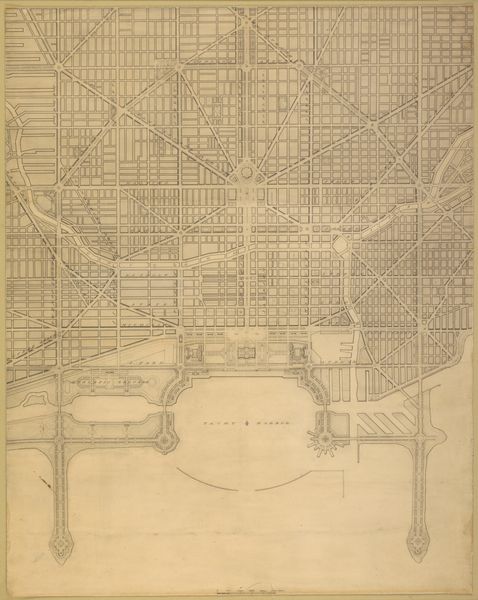

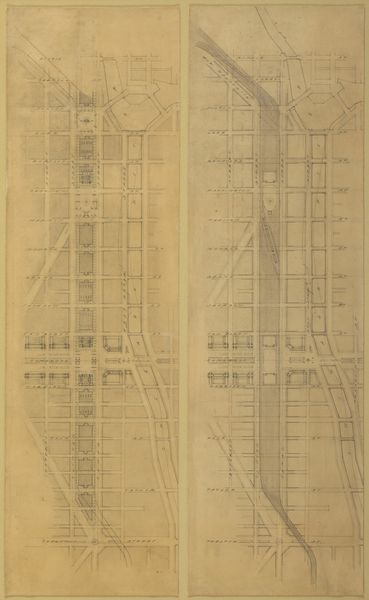

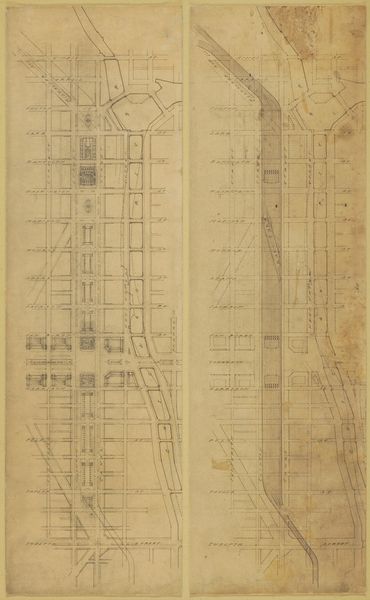

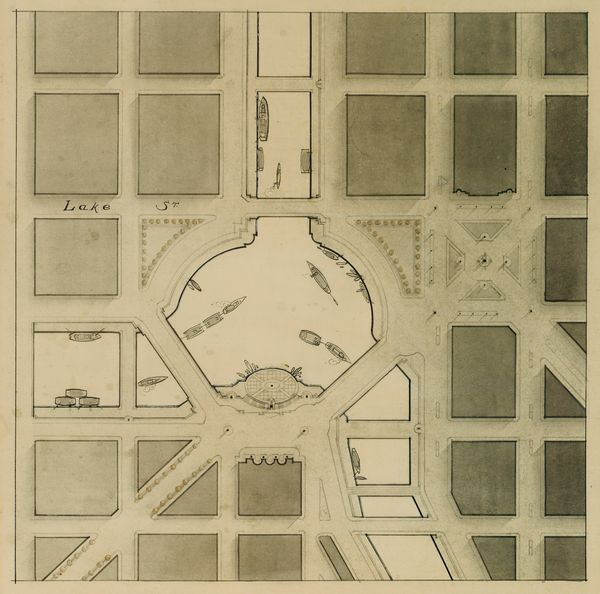

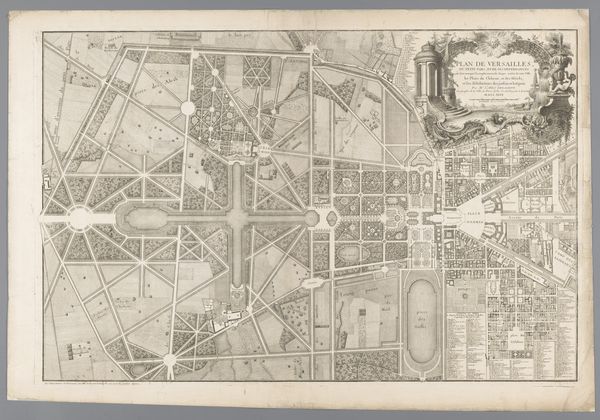

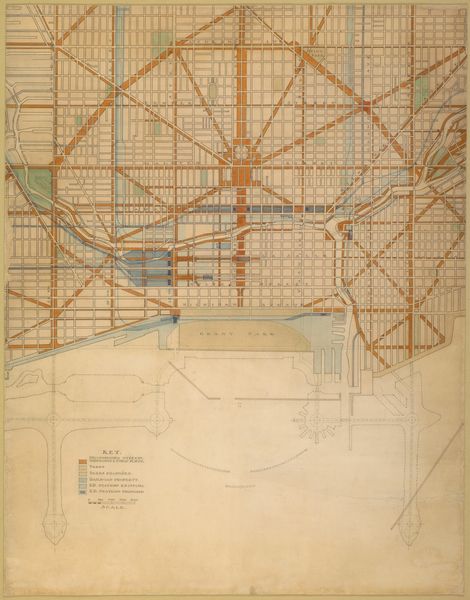

Plate 129 from The Plan of Chicago, 1909: Chicago. The Business Center of the City, Within the First Circuit Boulevard, Showing the Proposed Grand East-and-West Axis and Its Relation to Grant Park and the Yacht Harbor; the Railway Terminals Schemes on the South and West Sides, and the Civic Center 1909

0:00

0:00

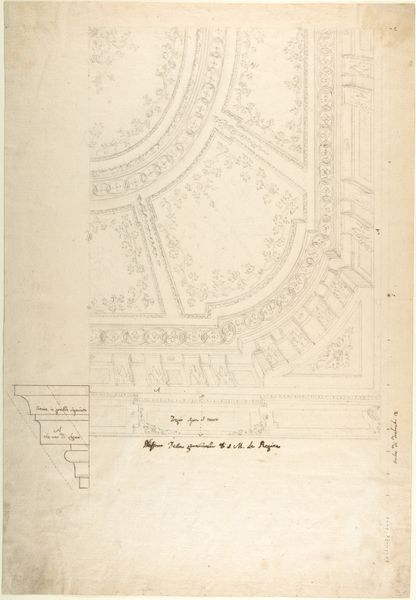

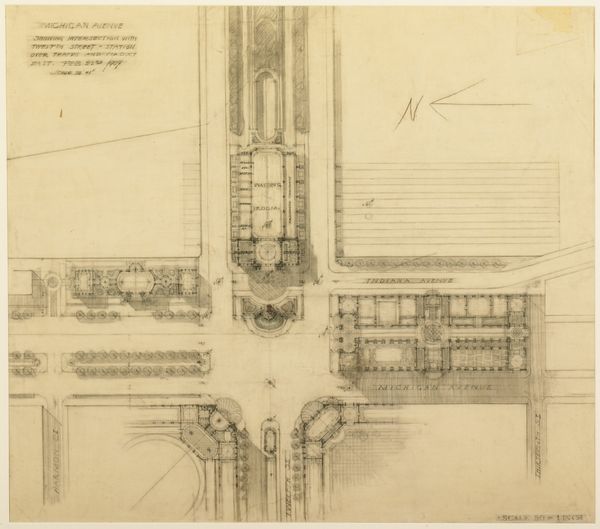

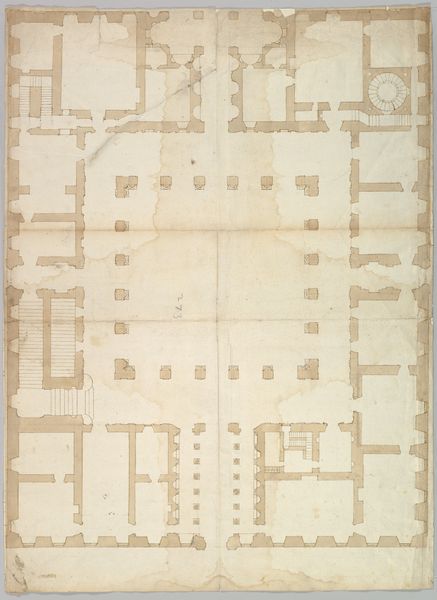

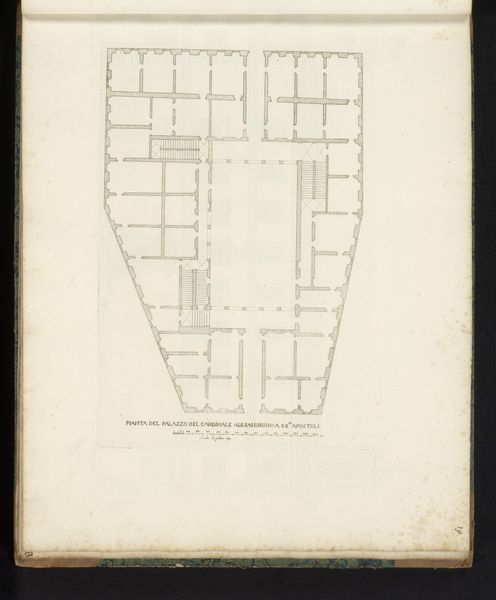

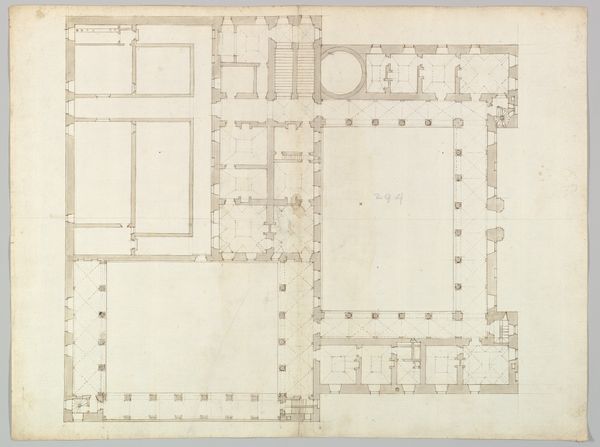

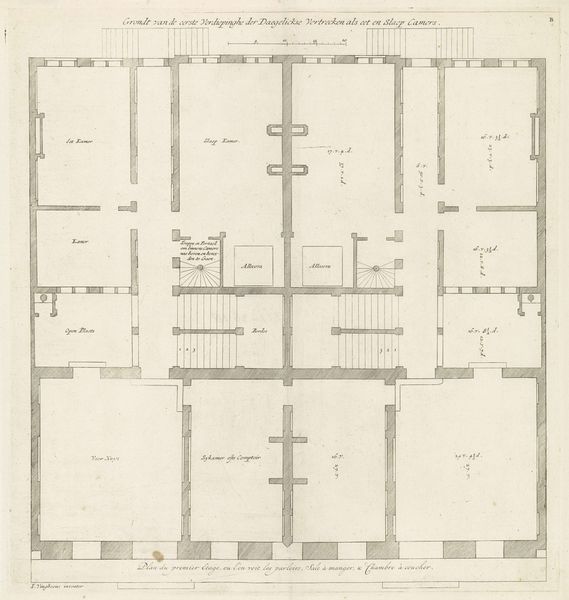

drawing, print, paper, pencil, graphite, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

paper

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

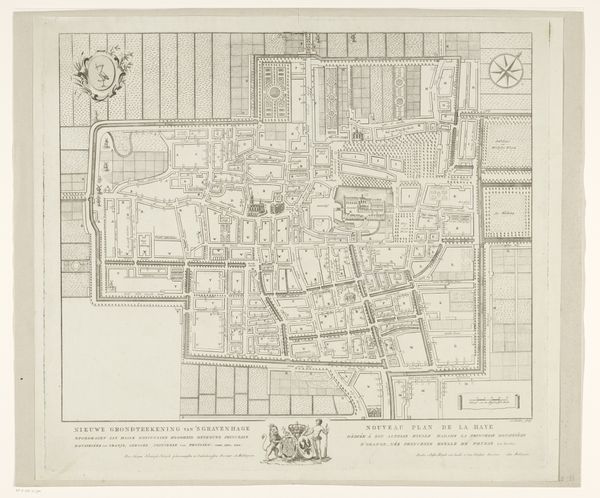

cityscape

#

architecture

Dimensions: 170.2 × 89.9 cm (67 × 35 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Look at this fascinating print from 1909, "Plate 129 from The Plan of Chicago," envisioned by Daniel Burnham. Editor: It’s dizzying, almost oppressive, with its rigid grid system bleeding across the page. It evokes a sense of top-down control, a dream of order imposed onto chaotic reality. Curator: Yes, there is a pervasive striving for perfection, you feel it too, a yearning to structure not only physical space but also society through architectural design. Notice the use of axial planning. This reflects a Beaux-Arts influence that favors symmetry and monumentality. Editor: And who benefits from this “grand” vision? Look how the railway terminals are prioritized. This design seems built for capital, for ease of movement of goods and for those who can afford it. The yacht harbor in the plan...it feels exclusive. Where’s the consideration for the working-class residents, the immigrant communities? Curator: That’s a crucial point. The City Beautiful movement, to which Burnham subscribed, often faced criticism for prioritizing aesthetics over social realities. However, if we consider symbolic expression, the planned civic center suggests an intention to foster collective identity and civic pride. Editor: Perhaps, but identity for whom? The plan implicitly encodes certain values – a vision of progress linked to economic expansion and a particular social order. Who decides which symbols are given prominence, and whose stories are erased in the process? Curator: Indeed, these designs always become sites of negotiation. How the city actually developed reveals which of these planned symbols resonated and which were left behind, unfulfilled. What we learn is that any city plan becomes something different than intended as the populations respond to it. Editor: Burnham’s plan becomes less about the concrete blueprints than about the ideologies underpinning urban development at the turn of the century—ideologies which, even now, we need to unpack and question. Curator: By carefully looking into the symbolism within the designs, as well as outside of them into the actual urban spaces that exist, a historical perspective helps us understand city plans, and the cities they create.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.