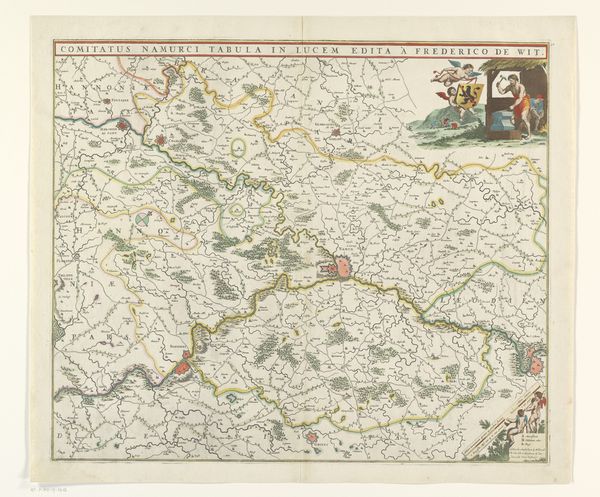

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

geometric

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 732 mm, width 511 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

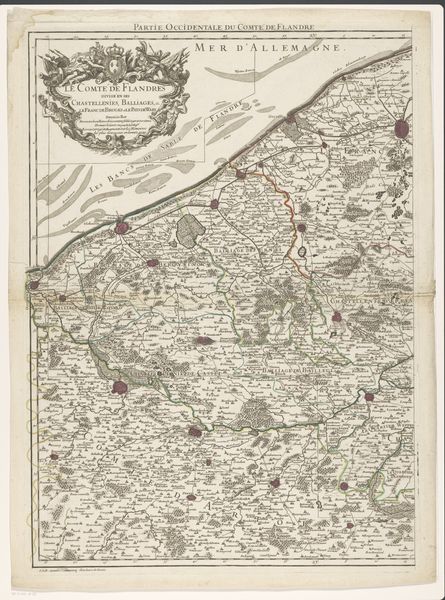

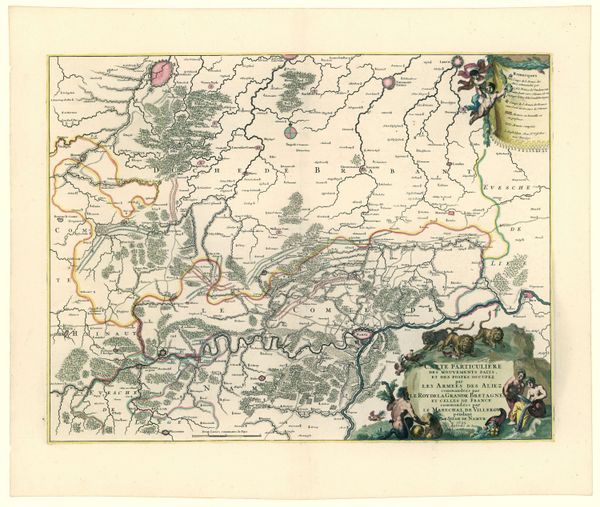

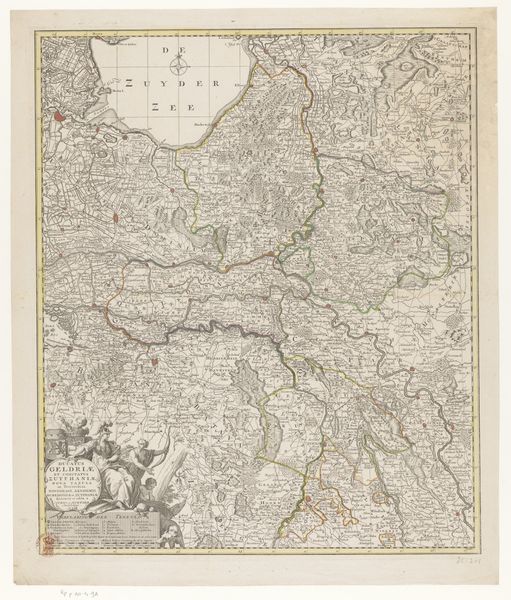

Curator: This engraving, known as “Kaart van het graafschap Vlaanderen (rechterdeel)” or "Map of the County of Flanders (right part)," dates to 1729. Its anonymous creator rendered this landscape of rule and realm onto paper using both print and drawing techniques. Editor: It feels remarkably detailed; looking at all these tiny topographical elements, my eye is pulled in multiple directions, a visual record not only of places, but their histories too. How can we see such a landscape now? Curator: As a document, the map depicts spatial relationships with precise intention. We see an intersection between geography, politics and early cartography; the artist provides a symbolic language where cities, roads, and borders acquire layered meaning, shaped by collective cultural understanding. Bruges and Ghent emerge as prominent landmarks in collective memory, imbued with symbolic power that transcends their literal representation on paper. Editor: Absolutely. A map such as this is far from a neutral representation; it serves as a powerful statement of ownership, delineating territorial claims through lines and symbolic markers. What’s most interesting is how it asserts and solidifies certain power structures; its borders literally "write" a very particular history of who belongs and who is excluded. Curator: But notice how the engraver balances objective rendering with aesthetic appeal, evident through meticulous lettering and decorative cartouches. Maps like these served not only pragmatic navigational requirements, but reinforced socio-political ideologies regarding place and people; this engraving invites us to decipher this nuanced symbolic tapestry of its time. Editor: It really prompts questions of who held the power to define and represent space, particularly within the historical context of territorial disputes. By understanding its embedded perspectives, we might ask ourselves what this visual history means, who it might exclude, and who stands to gain. Curator: Understanding cartography of this era invites critical insight regarding the dynamic connection between cartography and historical context, unveiling ideological narratives etched into geography. Editor: I think I can see how contemplating the power and ideology behind a seemingly straightforward map lets us read how such "neutral" objects are socially embedded—speaking volumes about an era’s anxieties, ambitions, and power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.