print, paper, watercolor

# print

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

watercolor

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 13 3/8 x 19 1/2 in. (33.97 x 49.53 cm) (image)

Copyright: Public Domain

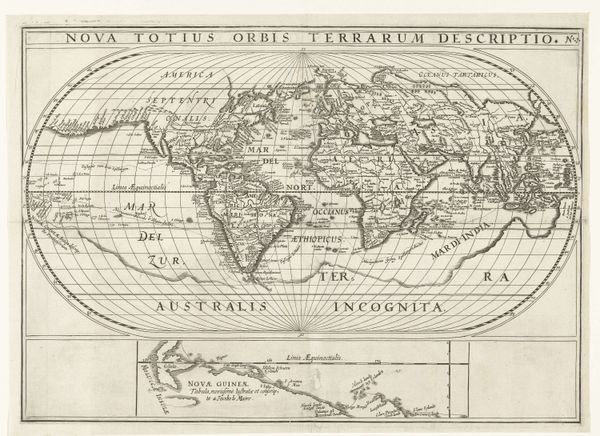

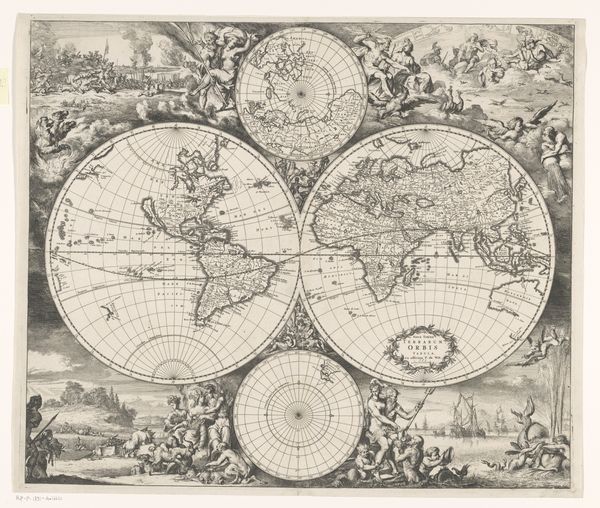

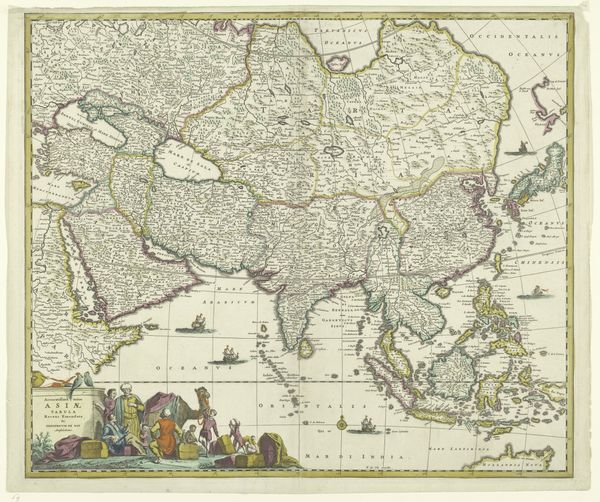

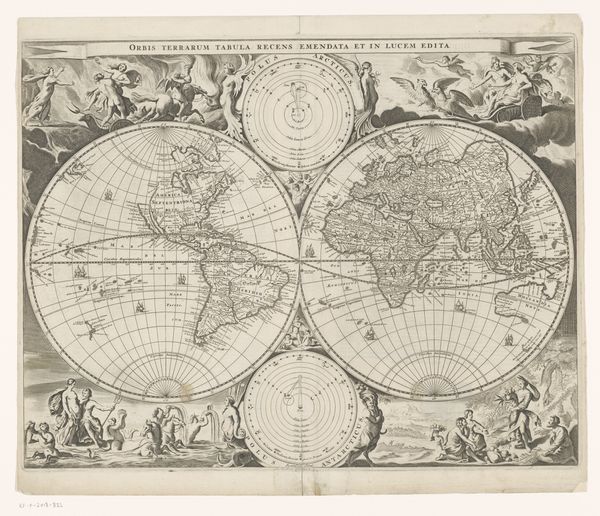

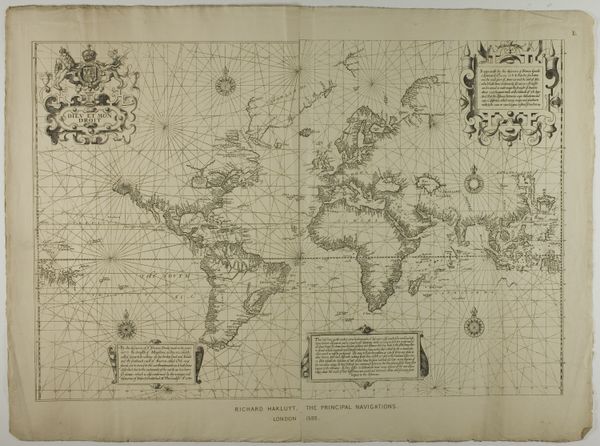

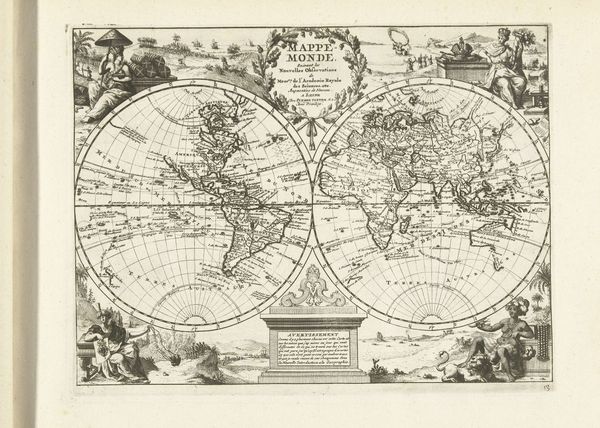

Editor: This is Abraham Ortelius' "Map of the World" from 1570. It’s a print on paper, touched with watercolor, and looking at it, I’m struck by how both familiar and alien it feels compared to modern maps. What stands out to you when you look at this piece? Curator: Immediately, I see a world laden with meaning, even beyond geography. The continents aren’t just landmasses, they’re stages for human drama, steeped in cultural assumptions and burgeoning empires. Notice, for instance, the prominence given to Europe and the relatively vague representation of the Americas. What does that visual imbalance tell you about the European worldview at that time? Editor: It suggests Europe was the center of the known universe, literally and figuratively. The Americas seem almost like an afterthought. Curator: Precisely! And observe "Terra Australis Nondum Cognita"--the "Unknown Southern Land". It's not just an empty space; it's a projection of desire and fear, a canvas onto which Europeans projected their fantasies and anxieties. These aren't merely geographical markings, are they? They're symbols charged with potent cultural energy. Editor: No, it's like looking into the minds of people from centuries ago. It makes me think about what future generations will see, or misinterpret, in our own maps and images. Curator: Indeed. This map is a reminder that every image, every symbol, carries within it layers of cultural memory and unspoken narratives. Even mistakes tell us something crucial about the worldview of the mapmaker. What hidden narratives do you suppose our modern satellite imagery conceals? Editor: That's a really interesting question, I need to think about it. This has changed the way I see historical maps. Curator: It invites us to look beyond the surface and recognize the powerful symbolism inherent in every depiction of our world.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Matteo Ricci brought a copy of this map with him to China, reportedly displaying it on the mission house wall. It so intrigued his Chinese visitors that they asked him to make one in Chinese. At the time, Ricci said, Their universe was limited to their own fifteen provinces, and in the sea painted around it they had placed a few little islands to which they gave the names of the different kingdoms they had heard of. For his own map, Ricci adopted Ortelius's oval projection of the earth and colossal southern continent. Yet he diverged from Ortelius in significant ways that show his familiarity with other European atlases. The St. Lawrence River in North America takes the form of a long narrow gulf, as in Gerard Mercator's map of 1569. The prototype for his description of the country of dwarves in northern Russia (see the wall panel with selected texts from the map) seems to have been the 1592 atlas of Petrus Plancius.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.