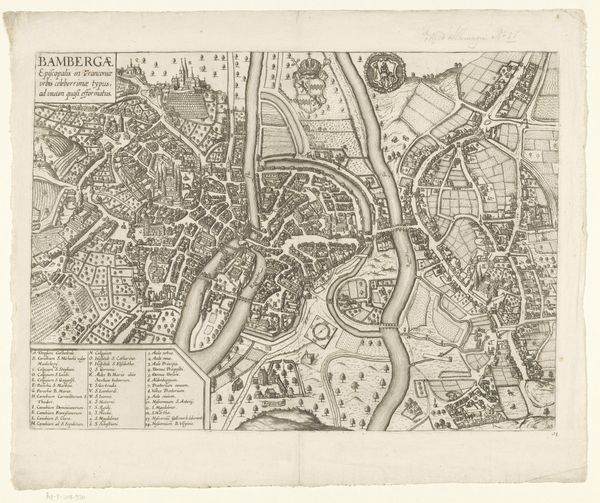

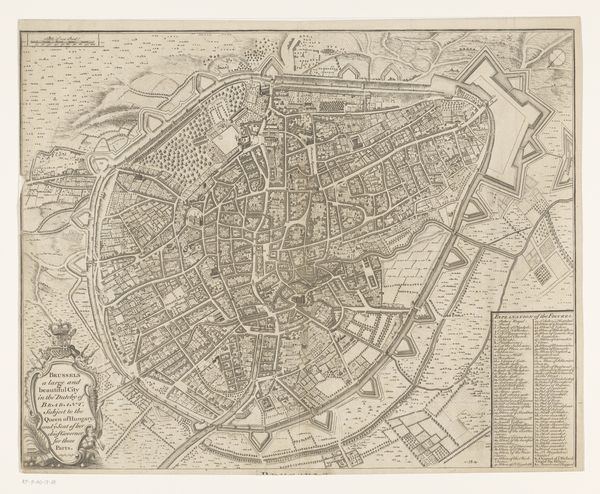

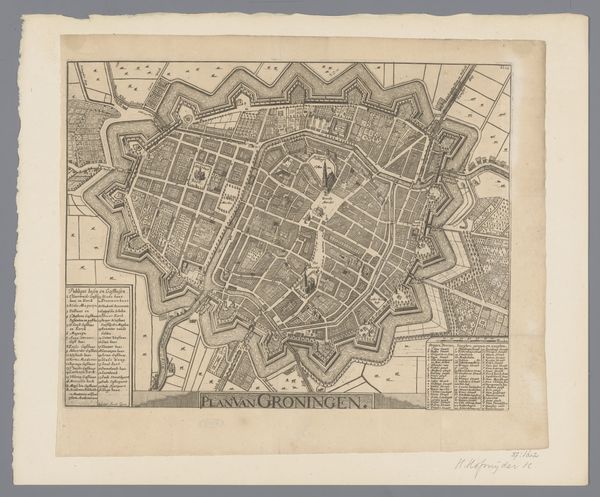

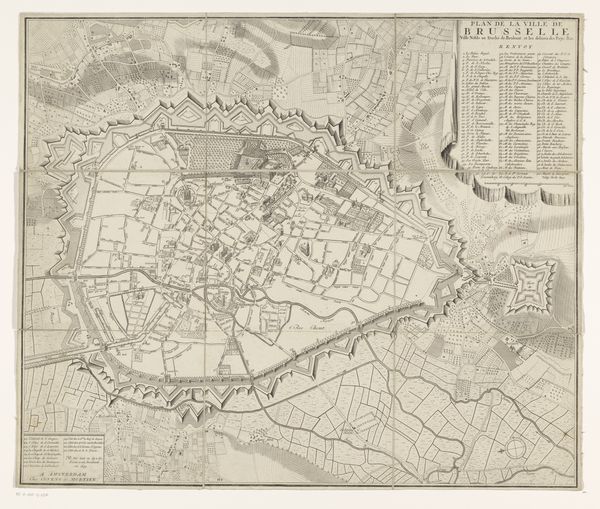

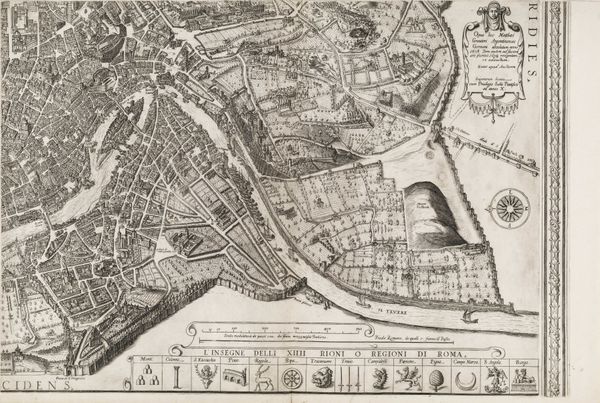

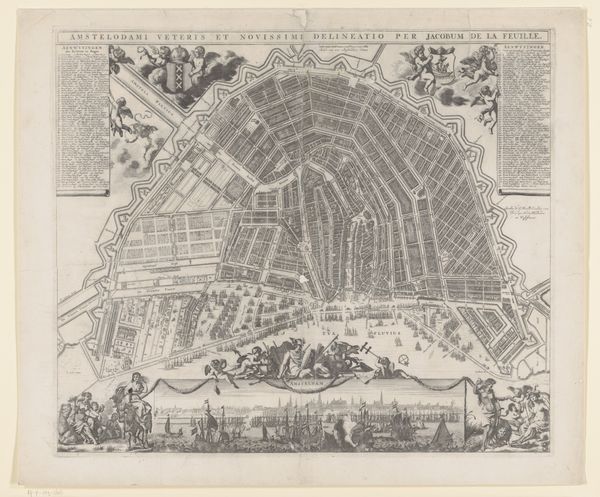

drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

etching

#

paper

#

ink

#

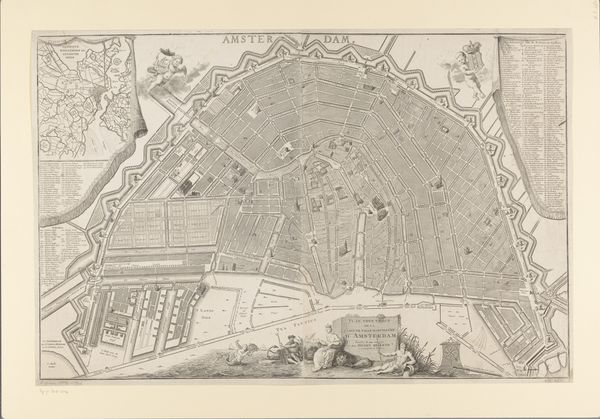

cityscape

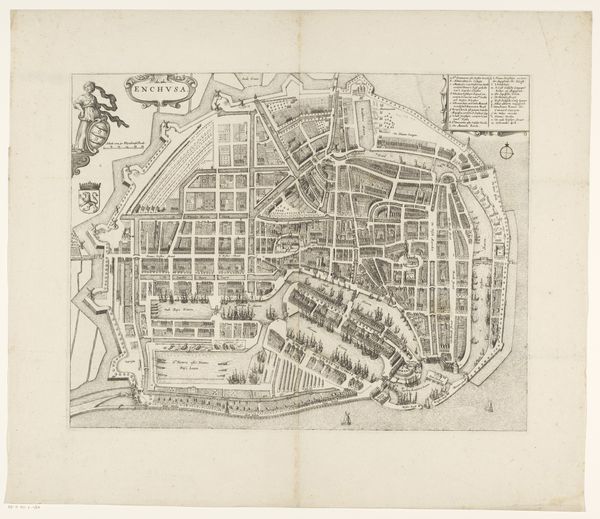

Dimensions: height 365 mm, width 465 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at Wenceslaus Hollar’s "Plattegrond van M"ünchen" from 1657, housed here at the Rijksmuseum. It’s an ink drawing, print, and etching all in one, rendered on paper. What’s grabbing your attention initially? Editor: The sheer detail! It feels incredibly meticulous. You can practically trace the city's layout and, I imagine, the lives lived within those tiny, precise structures. The density is striking, how they managed to make the houses like that. Curator: Maps like this weren't just geographic tools, of course. They served as statements of power. A carefully documented, planned city reinforced the Duke of Bavaria's authority, showcasing urban design as a political strategy of Baroque Europe. Editor: Absolutely. And the production itself – the labour! Think of the workshops involved, the skill of the etchers, the quality of the paper...it speaks to a very deliberate and I'm sure expensive process of construction. Did the ruling class decide to finance these pieces to show their power? Curator: Precisely. Consider the patronage system; the art produced was usually used as a statement of wealth. City maps like this often coincided with significant building projects, public works initiatives, or even military campaigns, aiming to boost civic pride and a show a projection of influence. The print was a kind of propaganda. Editor: It also makes me think about who this was for. The average person probably couldn’t read or access such a document, right? The accessibility and visibility is important here. It could influence a whole market in urbanism at the time and how city developments take place across social divides. Curator: That’s very insightful, given the period. Now, despite Hollar's precision, one can assume some artistic license was taken, especially when idealizing certain areas. It wasn't strictly documentation, more a performance of power and aesthetic taste combined. Editor: But the very act of mapping – isn't that always a construction? Deciding what to include, what to prioritize... it's a form of shaping reality itself. What decisions! What kind of work! Even the kind of ink and process they would have to undergo to come out with a finished material. It would’ve taken months. Curator: True, every map has its biases and choices baked in. What strikes me, though, is how this map represents a particular moment in Munich’s history, a moment deliberately crafted for external viewing and legacy. Editor: Agreed. And it makes you consider how those early processes are actually so essential. Each step determined to produce what is put forward in society to impact individuals. Curator: Indeed, from its social function to its detailed craft, there are many entry points into unlocking what the artwork truly represents and how we consume it in a world ever-changing. Editor: It makes one consider art is, from start to finish, a conscious, constructed reality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.