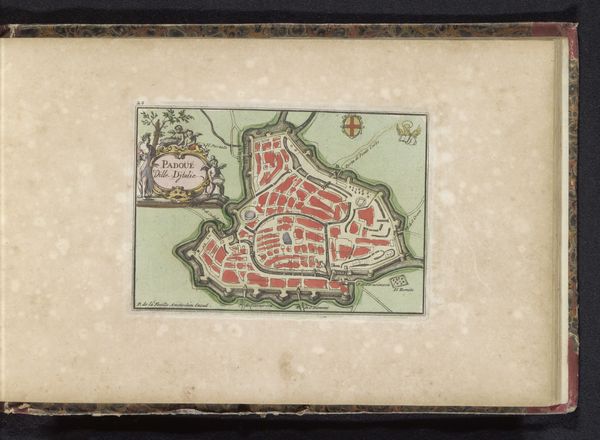

drawing, print, watercolor

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 128 mm, width 182 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

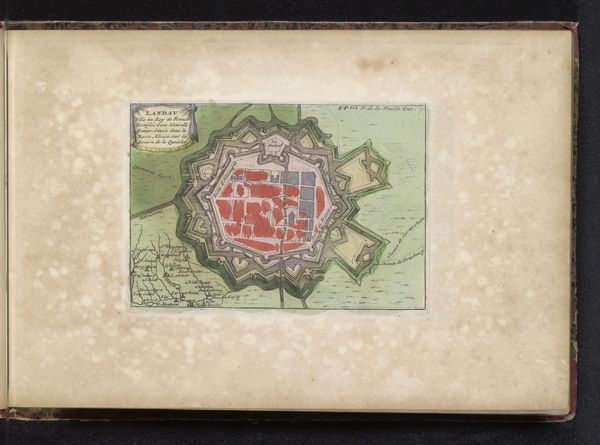

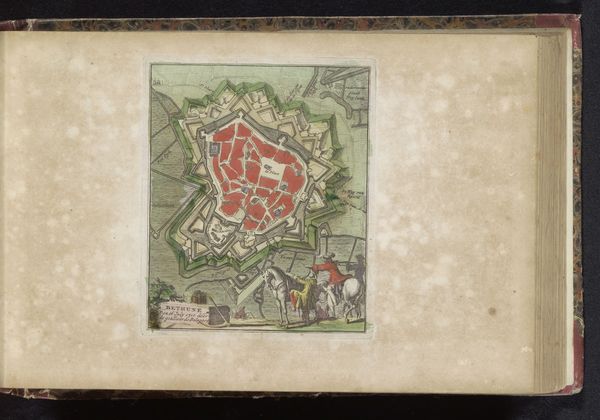

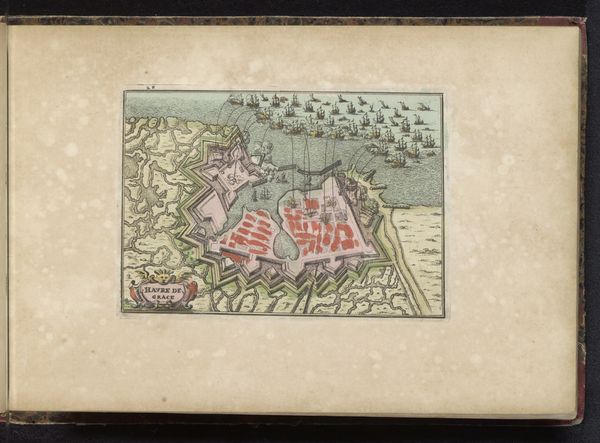

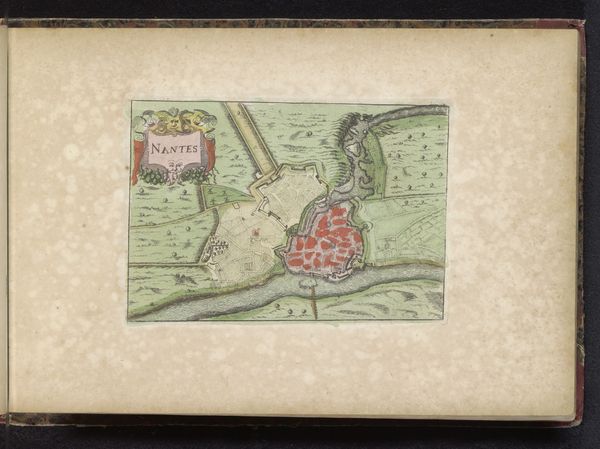

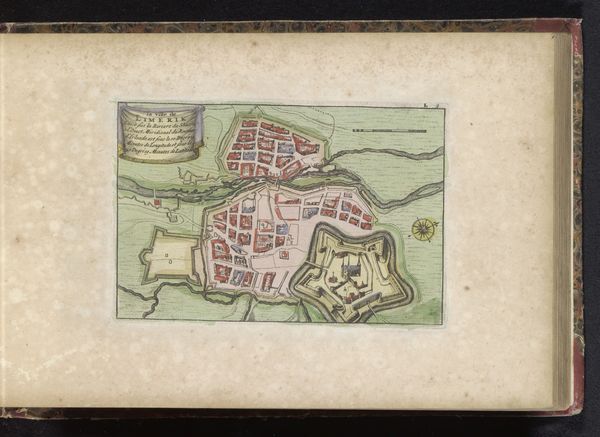

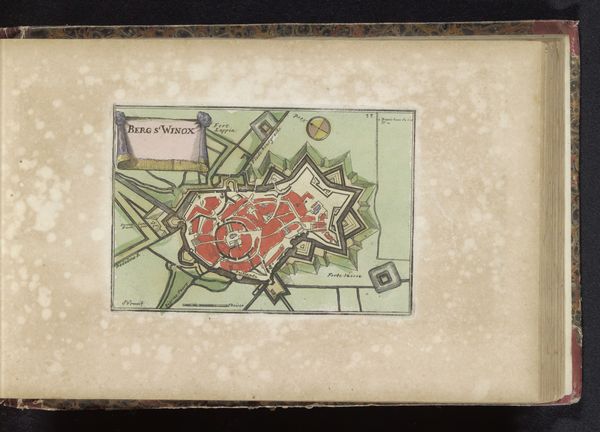

Curator: Here we have an intriguing work titled “Plattegrond van de stad Luxemburg,” dating from 1700 to 1735, by an anonymous hand. It seems to combine drawing and printmaking with watercolor finishing. Editor: It’s smaller than I expected. Seeing the washes of pale colour laid down over the crisp lines of the print gives the city an almost jewel-like quality. But that elaborate fortified outline… it suggests a place under constant threat. Curator: Indeed. Baroque cityscapes like this are fascinating documents. They offer a glimpse into how power was visually encoded through cartography. Notice the elaborate fortifications. The star-shaped layout wasn't just for show; it was a complex, geometrically calculated defensive system designed to withstand sieges. Think about what it meant to create such a controlled representation of urban space. Editor: Control…and expense. Those fortifications signify labor—an immense mobilization of manpower to reshape the landscape. The materials alone…stone, mortar, timber…everything sourced, transported, and then meticulously assembled. How does that imprint itself on the place, do you think? It must have structured every aspect of daily life. Curator: Absolutely. And the choice of materials and colours – pale greens, pinks, and reds – that speaks to an era when aesthetics and power were intertwined. The very act of depicting Luxembourg in this way reinforces its importance, solidifying its place within a larger European narrative. These symbolic visual strategies are fascinating, considering how deeply ingrained they are within the collective imagination of that era. Editor: I'm curious about the level of artistic labor invested here. Was this produced in multiple iterations in an artisanal workshop, or was it more of a singular creation intended for an elite clientele? The repetitive nature of city planning makes me think it would allow division of labor across printmakers, draftsmen, and colourists. Curator: Good question. What lingers with me is the layering of symbolic meaning. On one hand, it's a map, meant to inform and guide. On the other, it’s a symbolic statement – an attempt to immortalize Luxembourg. Editor: For me, I see a record of social power inscribed into the very earth. Art that is a product of intense labour. It's amazing how something so decorative reflects a rather brutal reality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.