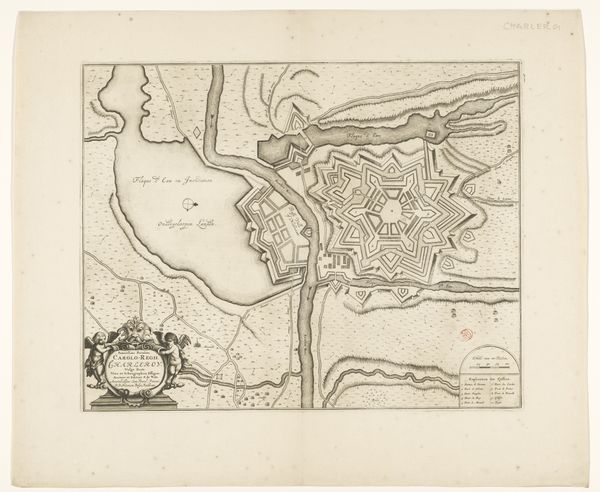

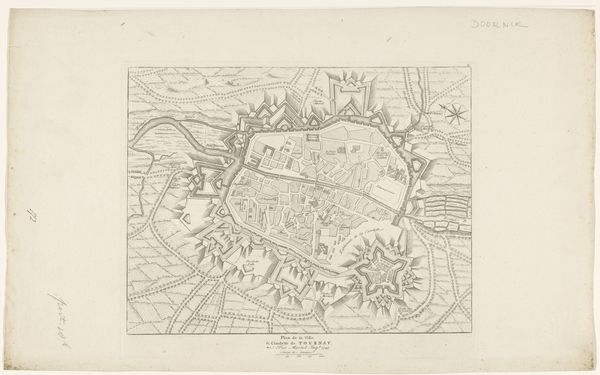

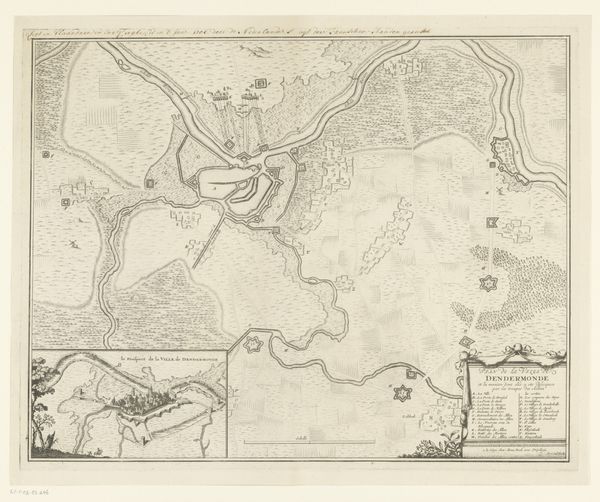

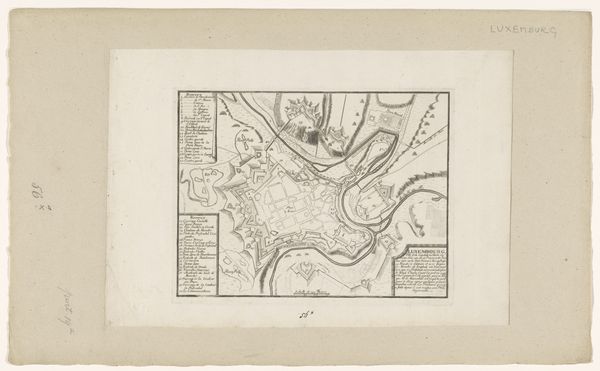

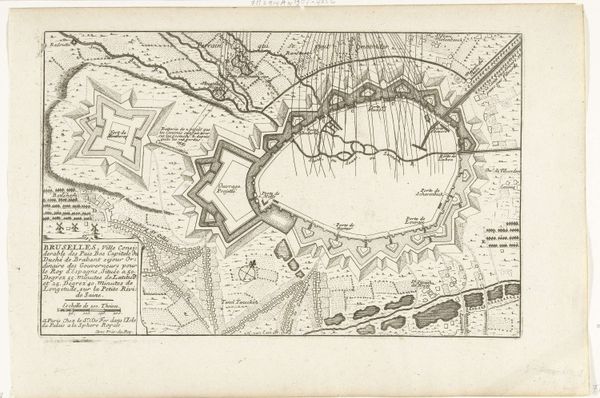

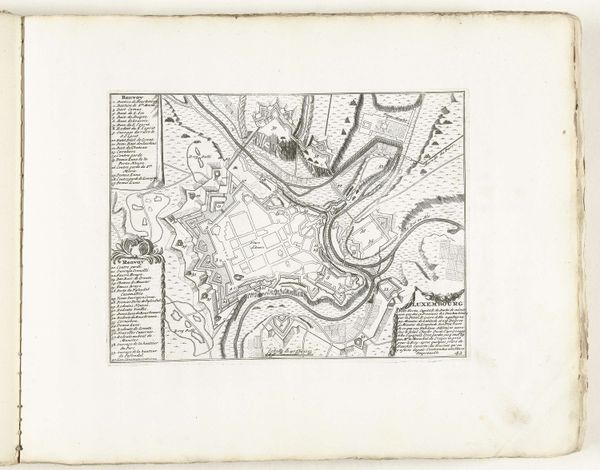

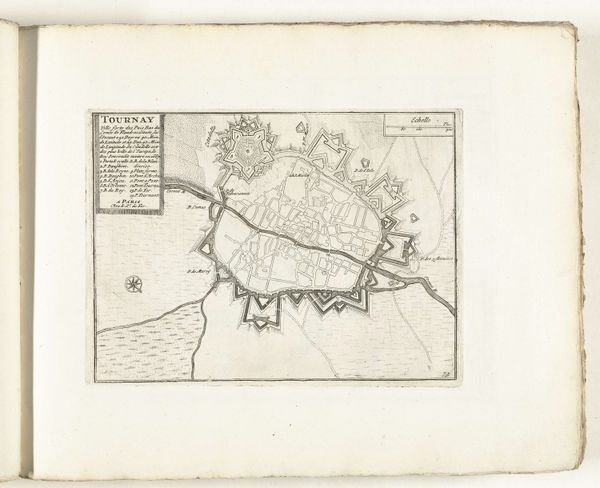

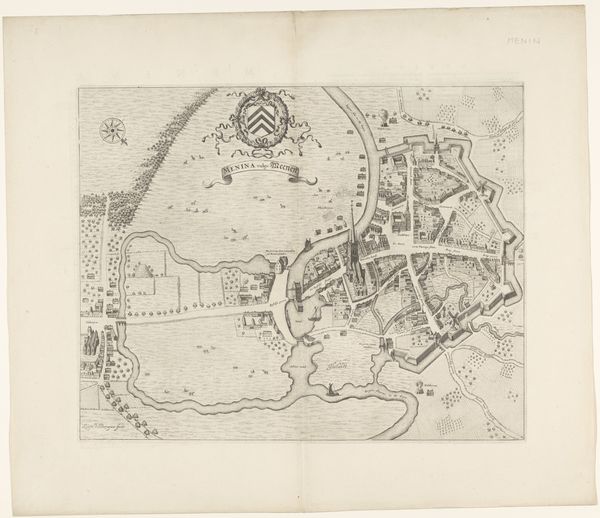

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

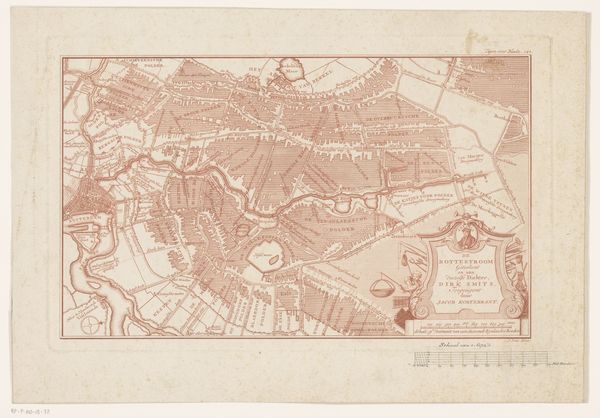

graphic-art

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

pen illustration

#

old engraving style

#

line

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

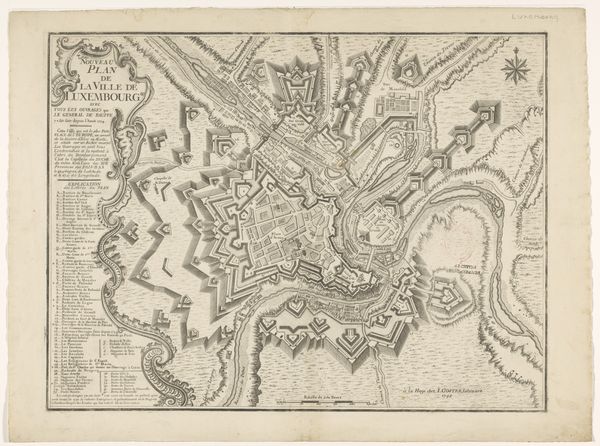

Dimensions: height 260 mm, width 362 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Beleg van Alkmaar, 1573" by Jan Caspar Philips, dating from 1745 to 1747. It's an engraving, currently at the Rijksmuseum. I'm struck by the incredible detail rendered using just lines. What stands out to you? Curator: For me, it’s how this print collapses the boundaries between art and cartography. We have an image purporting to depict a historical event—the siege of Alkmaar—but it functions just as readily as a map, useful for understanding the city’s layout and its surrounding landscape. What does that say about the ways prints circulated as both aesthetic objects and practical tools? Editor: So, the material, being a printed map, already tells us about its function. How did that function affect the production of it? Curator: Exactly! Engravings allowed for mass production and dissemination of information. Consider the labour involved: the engraver, Philips, meticulously translating a presumed battle into this reproducible format. Whose story does this tell, and for whom was it made? Who had access to these prints, and how might they have used them? It moves us from simply admiring an image to thinking about the whole socio-economic structure in which it was created and circulated. Editor: That's fascinating! I hadn’t considered the economic aspect so deeply. It makes me think about how the value isn't just in the "art" itself, but in its accessibility and how it served different societal needs. Curator: Precisely. Looking at it as a produced object helps us question the narratives around value and consumption and connect it to its place in a network of historical, economic and technological conditions. It makes you wonder what other stories lie hidden in the materiality of this print.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.