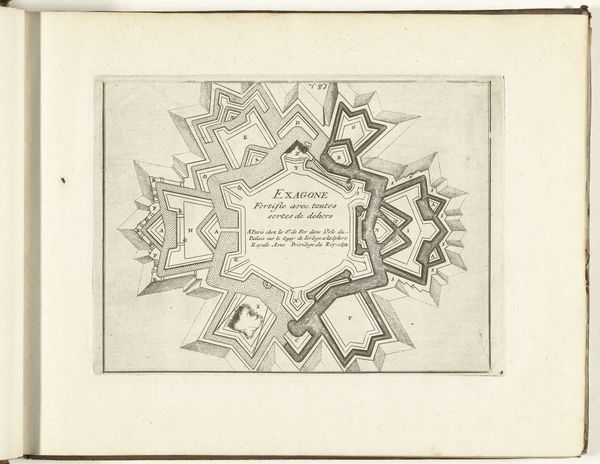

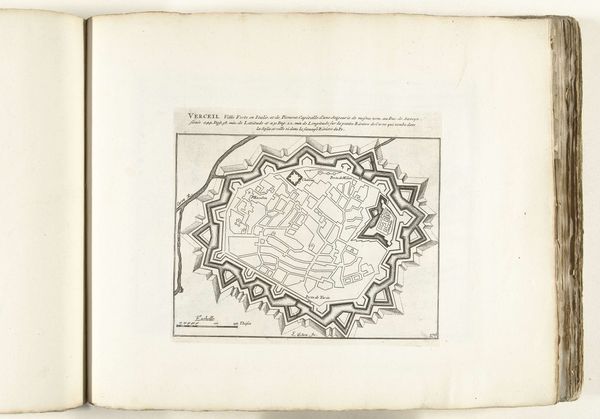

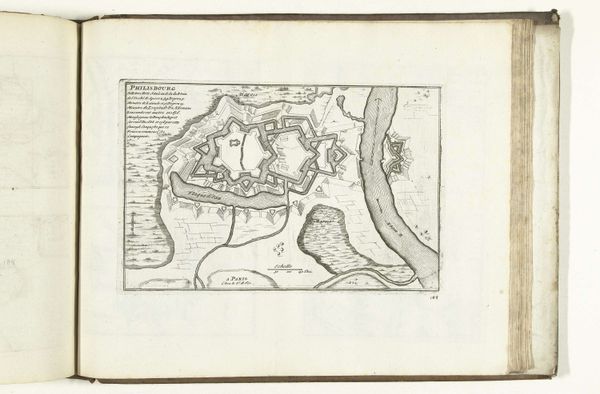

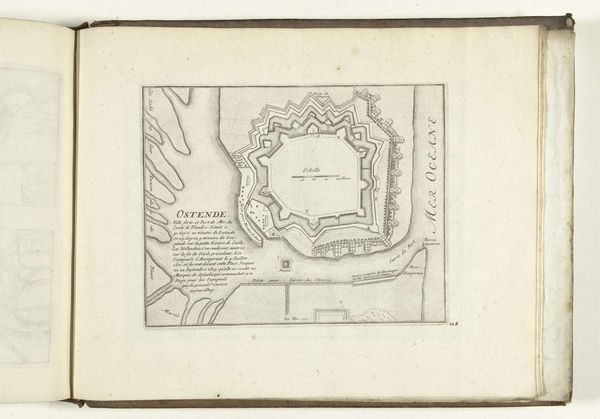

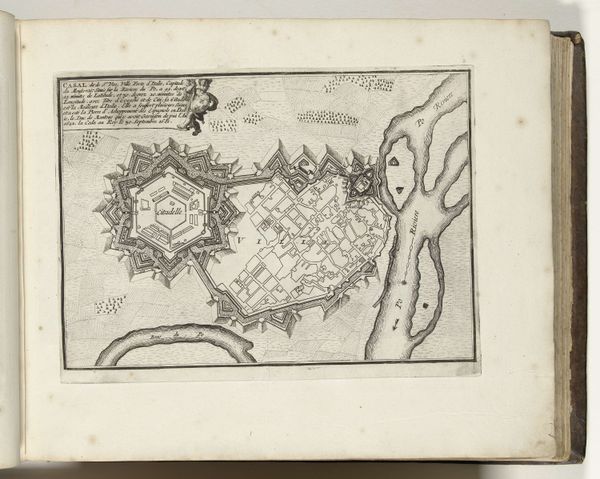

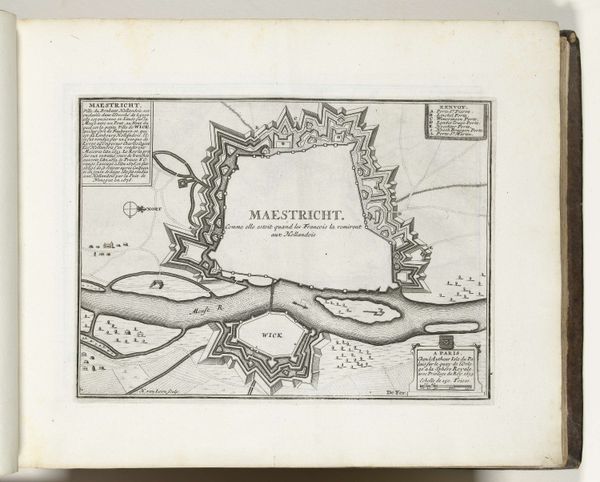

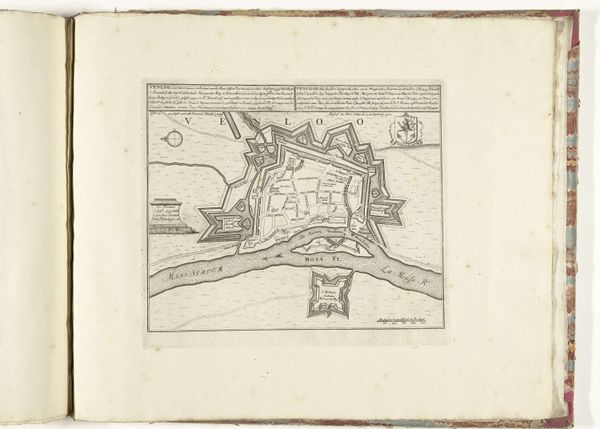

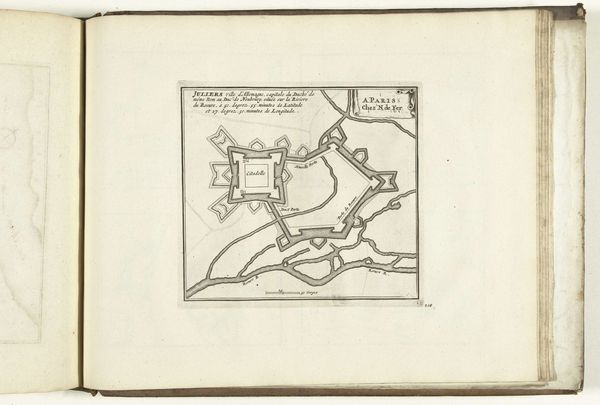

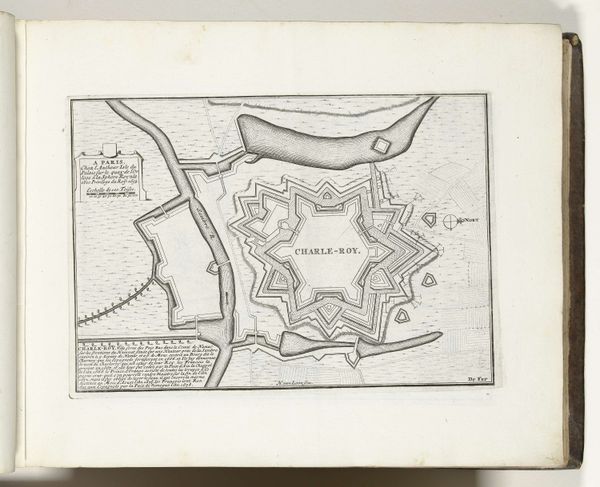

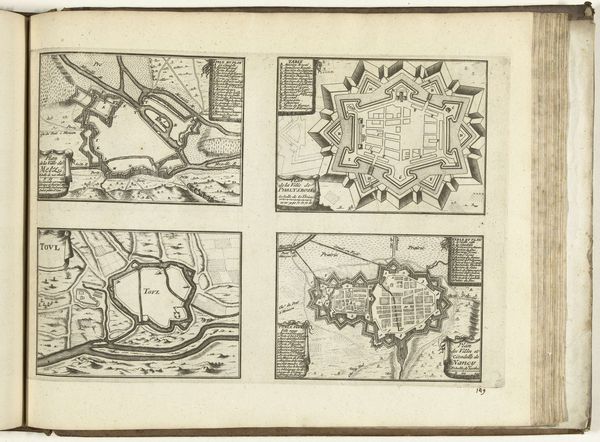

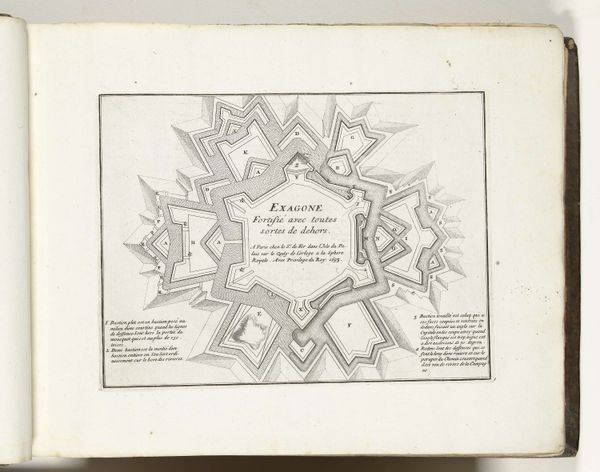

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 197 mm, width 258 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Plattegrond van Wismar, 1726", an anonymous print and ink drawing. I'm really struck by the almost obsessive detail; the entire cityscape is laid out with such precision. What can you tell me about this piece? Curator: Well, let’s consider the material conditions of its production. This isn't just a representation of Wismar; it's a document embedded in the military and economic landscape of the time. Engravings like these were crucial for planning, defense, and asserting power. Editor: So, you're saying the "art" here is secondary to its function? Curator: Not necessarily secondary, but intertwined. The skill of the engraver, the availability of paper, the patronage – all of this contributes to its value. Consider the labour involved, the workshops where these prints were made. This image is less about aesthetics, and more about logistics, the practical knowledge circulating at the time. It depicts labor power through both those constructing, defending and attacking, while suggesting resources available, geographically, and those controlling those assets within the state. Editor: I see your point. I was caught up in the artistry of the line work, but it's interesting to think about the economic and military systems it supported. What sort of "art market" do you suppose served that purpose? Curator: There wasn’t the art market we have now. Mapmakers would have had to contract out different aspects of the craft, like those producing the paper and those etching the plate; furthermore, in an economy increasingly reliant on mercantilist policy and colonial ambitions, such crafts were directly entwined with larger political-economic forces, connecting “high” art to practices generally regarded as ‘craft’. It’s important to emphasize those aspects, moving away from ideal notions of creativity towards means of production, class relations, modes of consumption. Editor: That changes how I see it completely. It’s not just a pretty map, it’s a snapshot of the power structures of the 18th century. Curator: Precisely. Next time you look at a piece, try tracing the materials and labor that brought it into existence. You might be surprised at what you find.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.