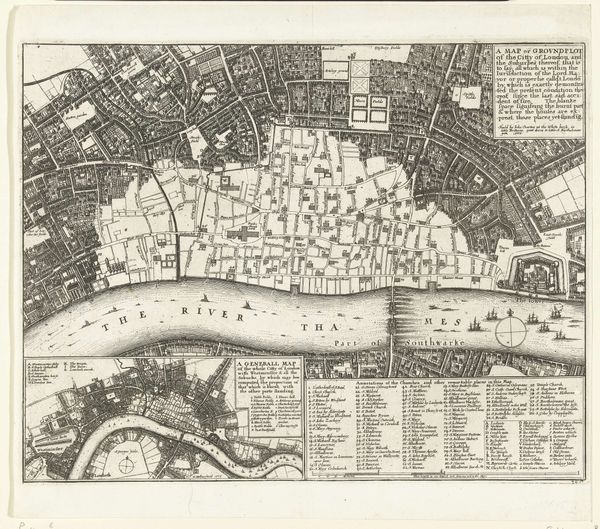

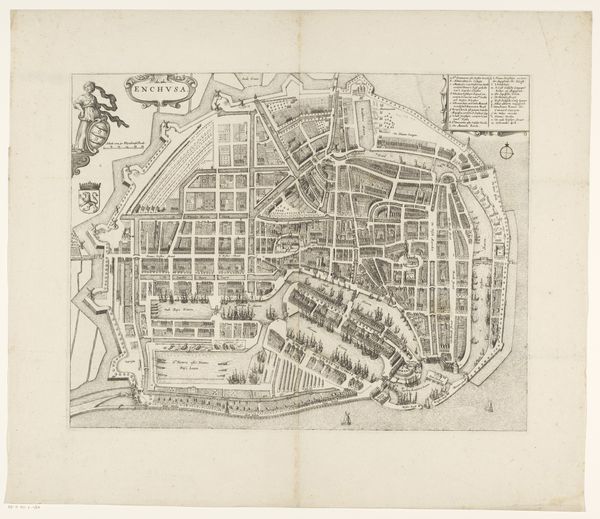

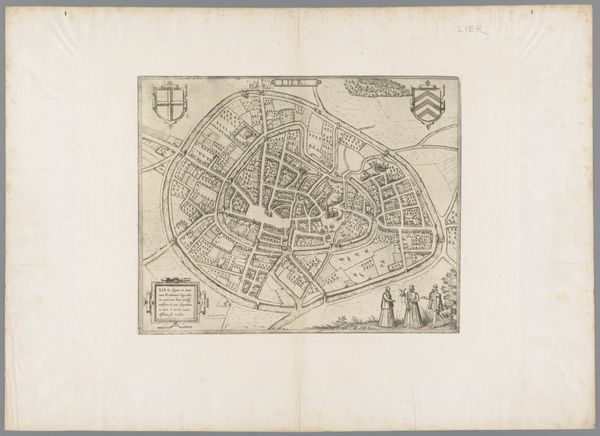

drawing, print, paper, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

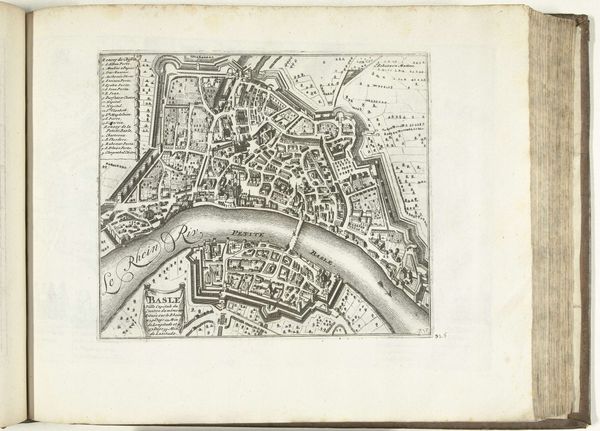

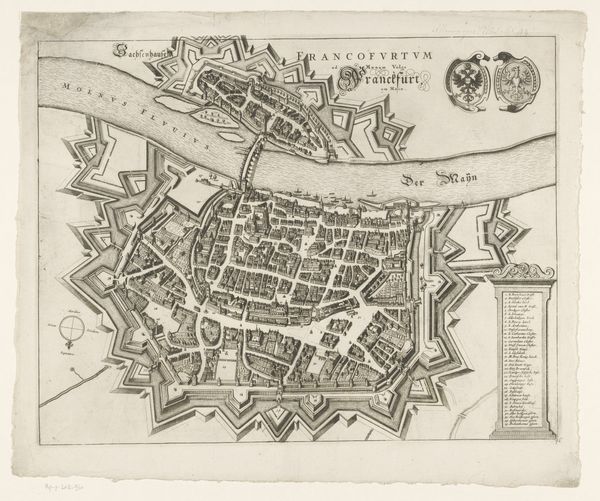

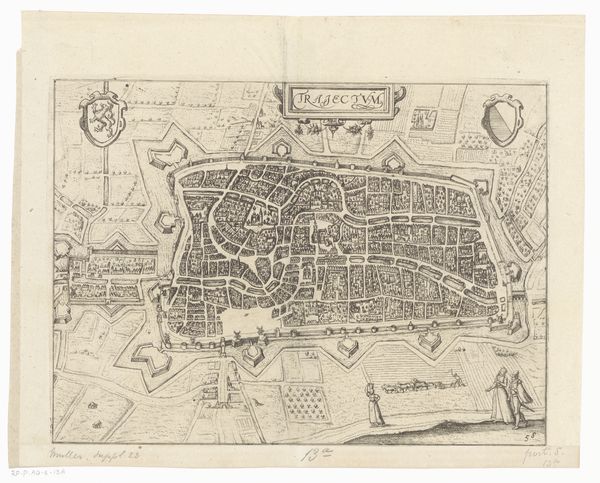

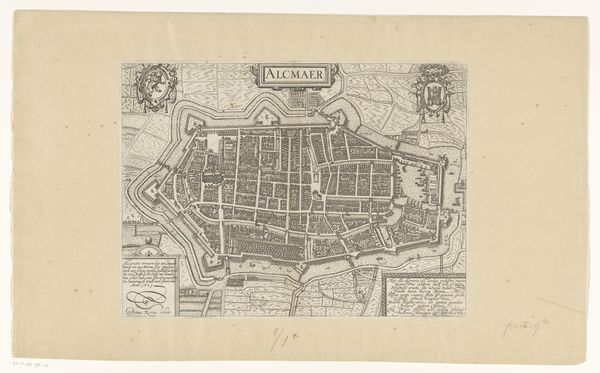

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 314 mm, width 522 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an anonymous "Plattegrond van Londen, 1761" held in the Rijksmuseum's collection; a printed and drawn map, using ink on paper. What are your first thoughts? Editor: I’m struck by the incredible density. Just looking at the sprawling networks of streets – the sheer volume of human activity implied is overwhelming. It feels like a portrait of ambition. Curator: Precisely. This wasn't just cartography; it served the burgeoning mercantile class. These city plans provided navigational tools, facilitating trade and control across expanding commercial networks. The ink and paper themselves speak to that early industrialization of information. Editor: The Thames dominates the visual field—a sinuous, arterial waterway snaking through everything. One could almost see it as an ouroboros, eternally feeding the city and taking its waste away. Curator: Indeed, its depiction is less an accurate representation and more an emblem of London’s lifeblood—power and exploitation condensed. I also see, encoded in these careful delineations of streets and squares, the story of the growing social divide that has only further entrenched itself. Consider the labor involved, from paper-making to printing and distribution, versus the lifestyles enabled for the merchant elite who employed these maps. Editor: What about the symbols embedded within the urban fabric itself? For instance, churches anchoring neighborhoods, asserting spiritual authority amidst urban sprawl, and what’s communicated when that symbol becomes minimized? Curator: Good observation. And consider the aesthetic intent – the clean lines suggesting order in what would have been, in reality, a cacophony of human life and labor. The making of it into something graspable, manageable – even aesthetically pleasing – sanitizes, perhaps even legitimizes the burgeoning inequalities of that era. Editor: So the image is a visual metaphor itself, where order belies chaos? This object offers, it would seem, layers that go far deeper than wayfinding; instead revealing the foundational iconography of class, commerce and empire in eighteenth-century London. Curator: Agreed. And, by studying the materials of its production alongside the urban iconography depicted, we start to see how closely material wealth was linked to control over both people and places, an era so similar and so different from our own.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.