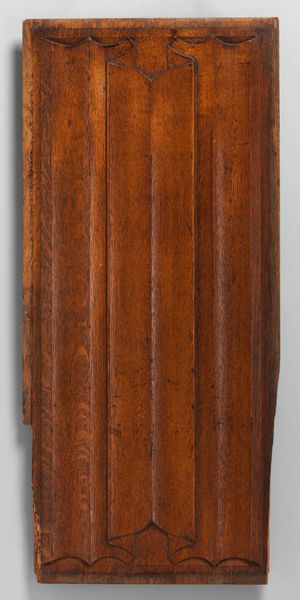

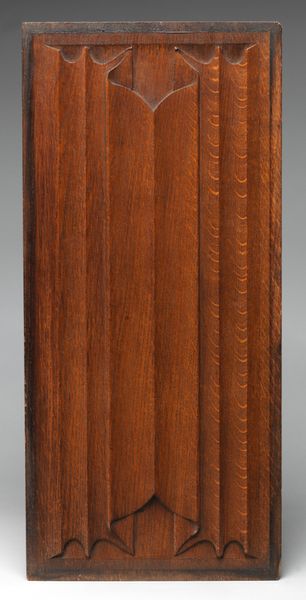

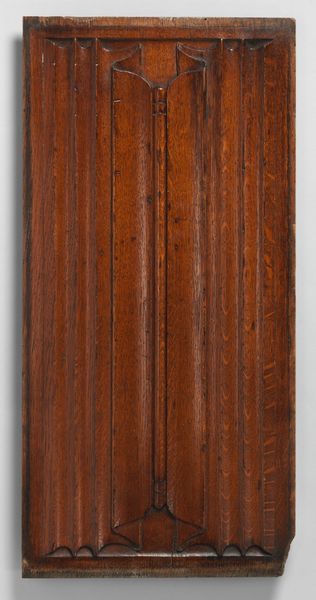

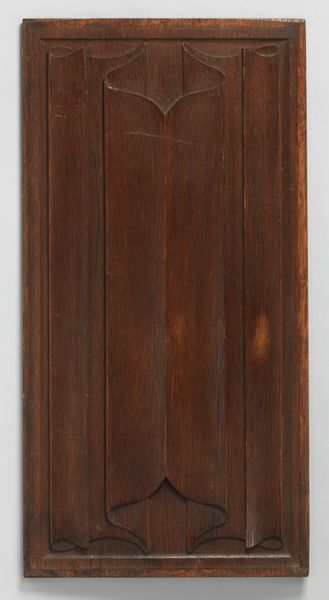

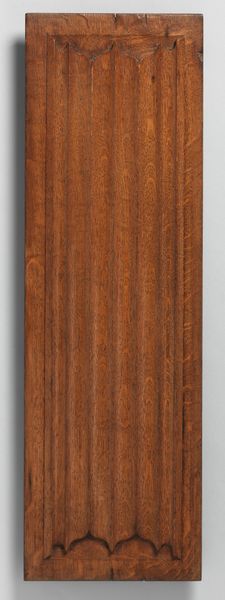

Panel from the Palace of Westminster 1842 - 1852

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 24 1/4 × 9 1/4 × 9/16 in. (61.6 × 23.5 × 1.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let's examine this Panel from the Palace of Westminster, crafted from wood between 1842 and 1852 by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. Currently, it resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. My immediate impression is one of austerity. The simple geometric shapes carved into the wood evoke a sense of order and somber formality. Editor: Austerity is certainly a reading I acknowledge in relation to this panel, but one I find problematic, for that particular design choice occurred against a historical backdrop of profound societal shifts in Victorian England, where industrialization wrought visible and class-based horrors. Pugin was advocating a reimagined Medievalism rooted in his socio-political position in contrast to that perceived degradation, which in that time was inextricable from the Gothic aesthetic in moral terms. Curator: An intriguing counterpoint. Let us examine Pugin's architectural philosophy as articulated by the medium of sculpture in a formal setting, the carved wooden paneling and molding detail. Note how the lines converge vertically, almost guiding the eye upwards. It seems that the artist employs an established visual vocabulary of line and space—form and order, but little dynamism. Editor: True. The geometry functions precisely, recalling for contemporary and current observers a longing for what was never achievable. To engage only with the sculpture is to forget the legacy of architectural revivalism to which he committed his art as resistance; consider its intersection with a specific aesthetic yearning in relation to contemporary critical discourses about social reforms, such as better labor laws or access to clean water—which can be tied back now to how marginalized populations often find solace or a form of political speech embedded or projected by artworks even now, with objects becoming cultural markers or vessels for suppressed identity. Curator: Even divorced from this object's placement or social and historical context, the repetition of these pointed arches, and the rhythm it creates is appealing. These recurring triangular motifs speak of stability through careful arrangement— Editor: Which you correctly note; however, it’s important to also account for its Gothic and therefore religious signification, specifically, by engaging the sociopolitical and material conditions where those motifs meant something within certain hierarchical, and in this context British systems, since meaning never occurs in a vacuum but through contextual framing, it becomes not an issue of merely design itself as it has the potential of becoming a social signifier to be interrogated about the ways these patterns are reproduced even nowadays. Curator: Perhaps we've both brought unique viewpoints. For my part, considering line, material, and form gives us insight into understanding these artistic decisions that comprise its presence. Editor: Indeed. By looking deeper into that interplay between aesthetic choices with historical factors at play around artworks opens dialogue of critical relevance that invite others to reflect beyond visual impressions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.