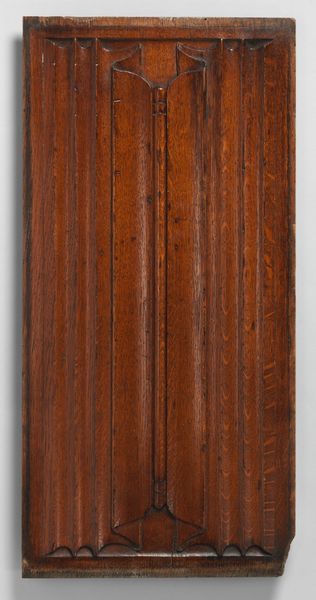

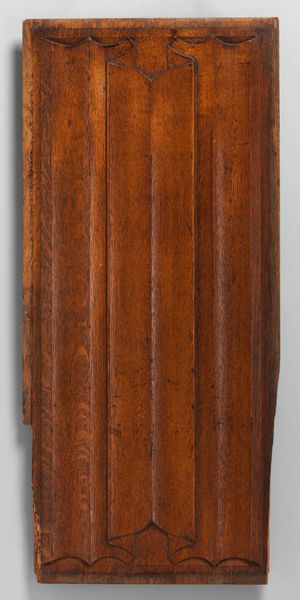

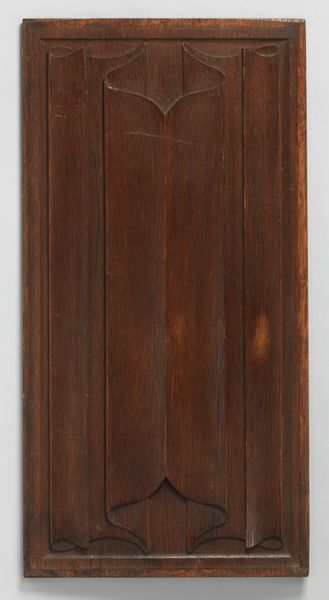

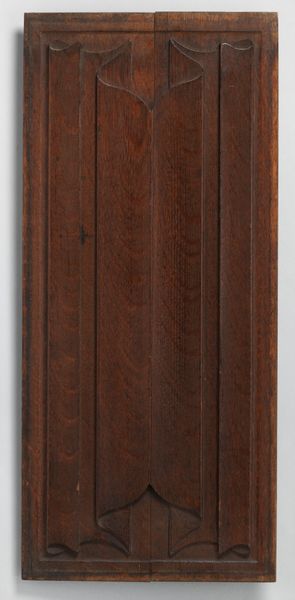

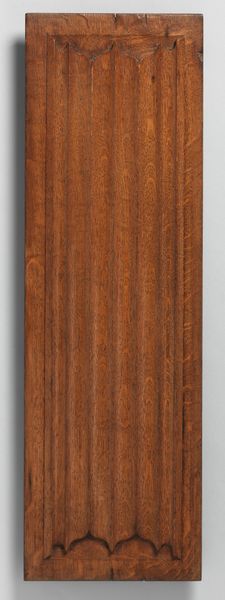

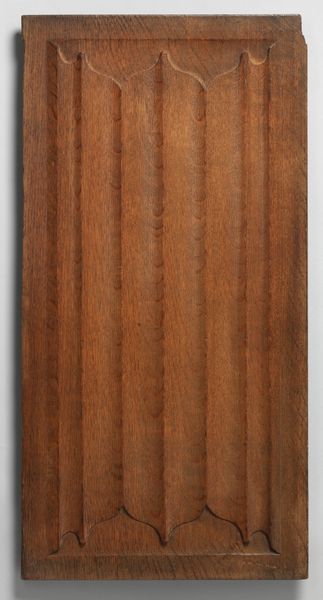

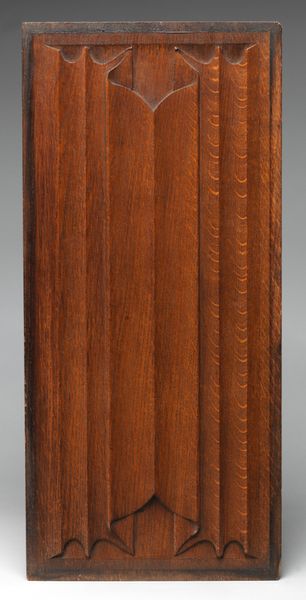

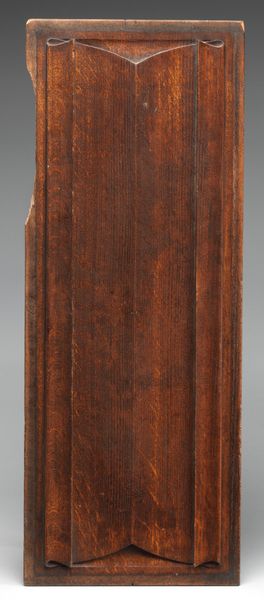

Decorative paneling from the Palace of Westminster 1840s - 1850s

0:00

0:00

carving, sculpture, wood

#

wood texture

#

medieval

#

carving

#

sculpture

#

wood

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 20 × 12 5/16 × 5/8 in. (50.8 × 31.3 × 1.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us is a decorative panel hailing from the Palace of Westminster, dating from the 1840s to 1850s. It is attributed to Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. Editor: It looks so…restrained. The texture is almost monotonous, a relentless series of vertical grooves. Although, the wood itself looks lovely and rich. Curator: Restraint, indeed, is a key characteristic. Consider the composition: a field of vertical fluting, capped top and bottom with simplified, stylized motifs – minimal variation across the entire visual plane. This reflects Pugin's devotion to Gothic Revival and its principles of structural honesty and decorative unity. The pattern embodies simplicity, almost austerity. Editor: Austerity certainly comes through. But let’s consider the material. It's clearly hand-carved, the lines and geometric patterns cut by skilled artisans. There's labor embedded here. Think of the sheer repetition, the time it took to produce not just this panel, but hundreds like it for the Palace. The inherent value rests as much on the repetitive work involved in construction as any pure artistic inspiration. Curator: Undoubtedly, craft plays a central role. Yet, beyond its making, examine how the visual elements create a system. Observe how the vertical lines establish a sense of order. Then notice the ogee arches placed in relation to these straight verticals—a dialogue of form. Editor: And that dialogue speaks volumes about Victorian society's understanding of labor and ornamentation, I agree. It reveals the economics of production wherein large teams contributed anonymously to the making of what might seem from a distance like high design. Curator: Absolutely, by deconstructing this seemingly basic construction, and recognizing it as both material and sign, we reach a richer reading. Editor: Exactly. Recognizing art in terms of process as well as the product itself lets one start acknowledging value for people and process rather than pure beauty. Curator: In scrutinizing this single piece we can understand production systems that speak to material history through shape, rhythm and tone. Editor: And by engaging more directly with materiality, process, labor and craft we might arrive at more radical assessments concerning not only palaces like Westminster—but every piece displayed today in the museum context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.