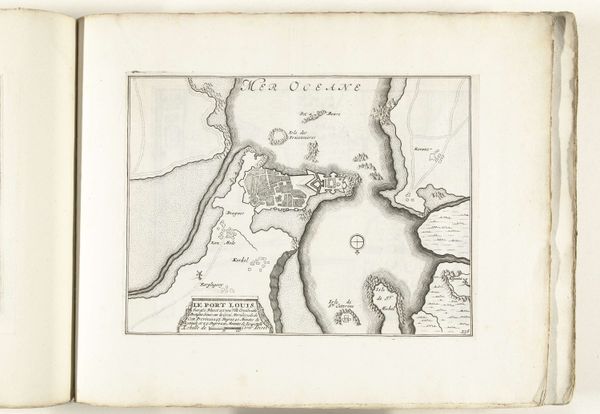

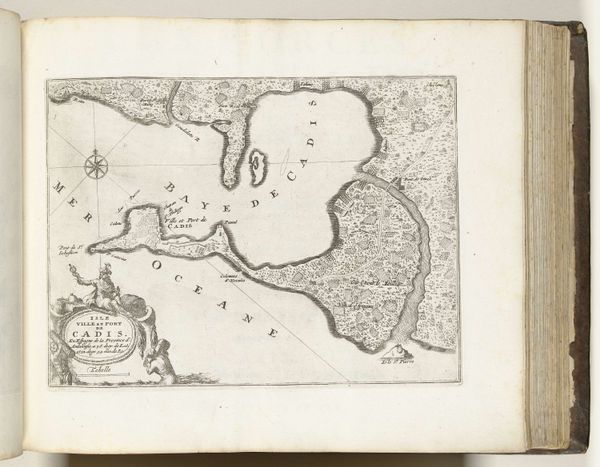

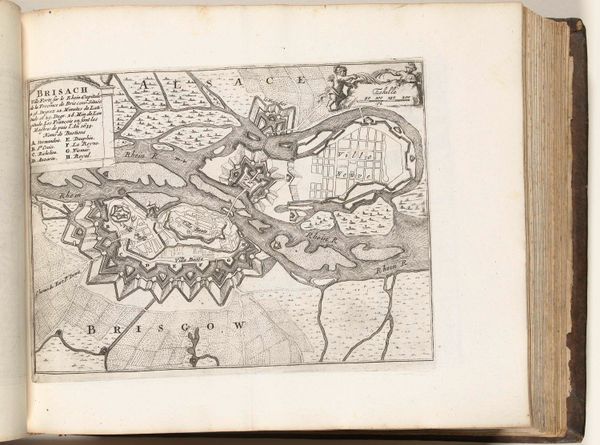

drawing, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

landscape

#

ink

#

pen

Dimensions: height 230 mm, width 293 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

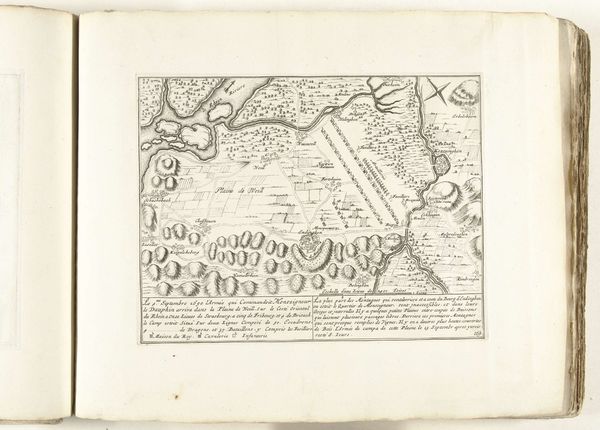

Curator: Ah, there’s a peculiar kind of beauty in the clinical gaze of this map, isn't there? We’re looking at a pen and ink drawing from around 1693-1696, titled "Plattegrond van Port-Louis." It's attributed to an anonymous artist and is currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression? Stark. It's a land seen from a removed, almost God-like perspective. All sharp angles and tentative renderings of terrain; the work hums with the precision of calculation. Curator: Absolutely. The precision tells us much about the period's hunger for control, not just of the land, but of understanding it. It also gives clues about Baroque sensibilities, of course. Editor: Maps have always struck me as psychological portraits of their creators, more than geographic documents. What kind of self do you have if you feel the need to master a place like this, rendering it into such contained, intelligible pieces? And what about the symbolism? Water signifying fluidity, potential danger… land being stability and claim. Curator: Indeed, I can only imagine the debates such maps ignited! What is knowledge itself, if not control through understanding? Still, you can imagine how the representation flattened lived experiences of real inhabitants. But notice, too, the little clusters of buildings, attempting a balance in perspective. Editor: What always interests me is what is left out. The artist has shown buildings in simple shapes but not how they interact with one another. The human lives are almost non-existent and only referenced with the name Port-Louis. Are we supposed to infer from their omission, the place's newness, and supposed blankness? Curator: That’s the great question of these kinds of landscapes. I guess what it really is saying is that if the details matter, this map may not be the tool for that kind of reading of reality. Editor: That almost brings us full circle in the conversation: as objects and portraits, these kind of creations often tells us more about their era, with all of their complex tensions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.