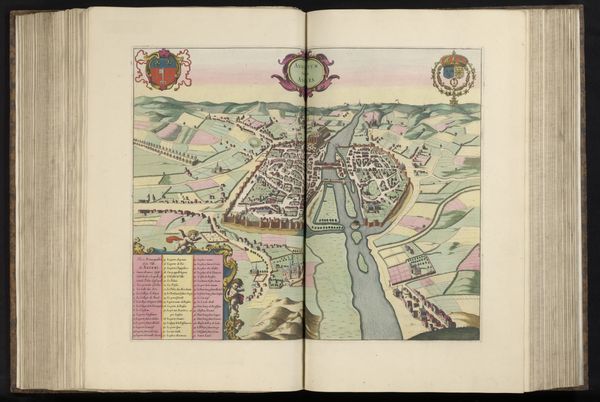

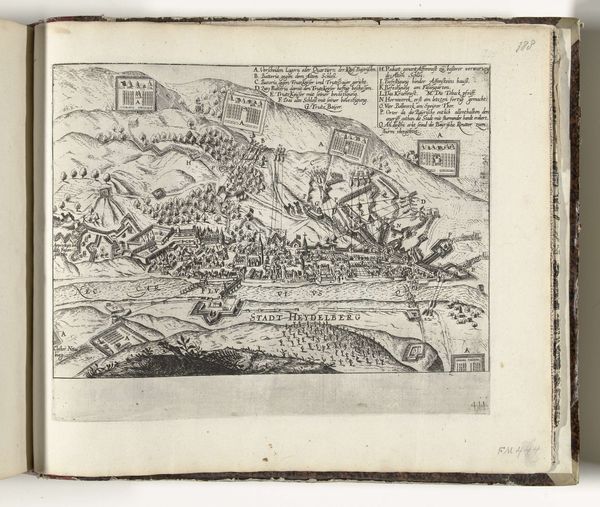

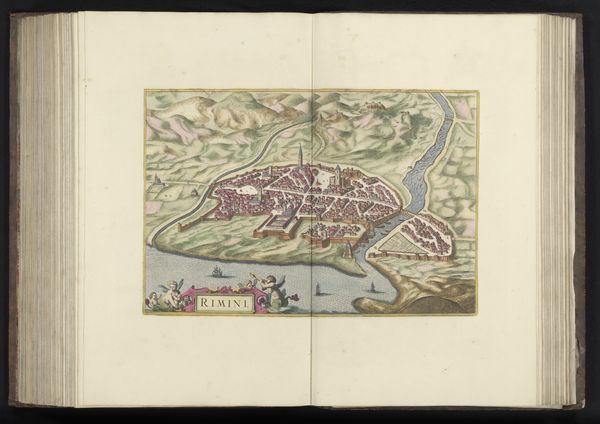

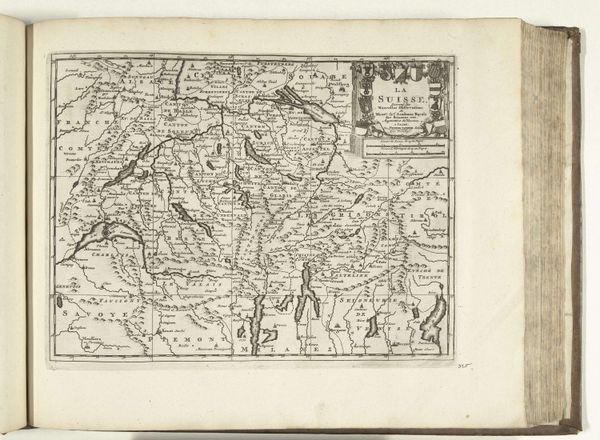

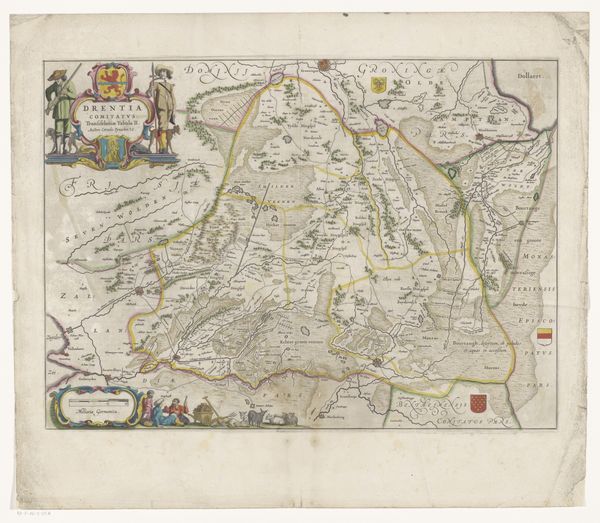

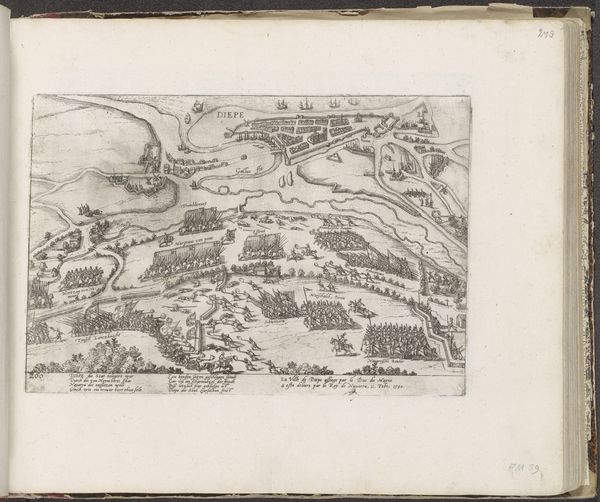

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 370 mm, width 449 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

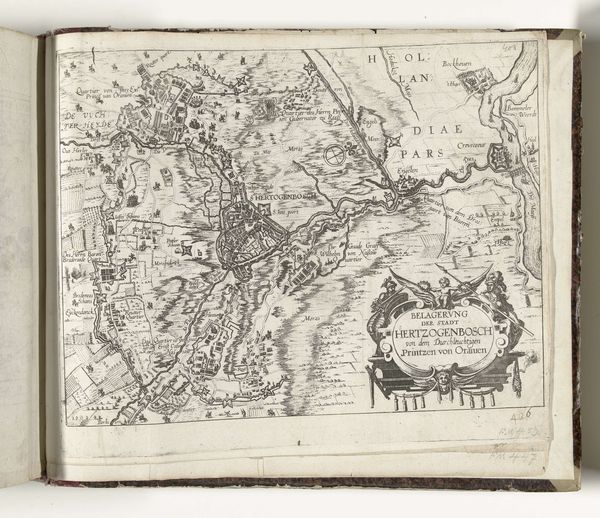

Curator: This print, "Gezicht op Siena in vogelvluchtperspectief," which roughly translates to 'Bird's-eye view of Siena', is attributed to Wenceslaus Hollar. Created sometime between 1617 and 1717, this piece captures the cityscape in striking detail using ink on paper with engraving as a key technique. Editor: My first thought is, wow, this city feels incredibly planned and contained, almost like a little jewel meticulously placed in the landscape. The color palette feels deliberate; that muted palette feels so organic and yet meticulously ordered. Curator: The ordering you're seeing speaks to the power structures in place during the Italian Renaissance. Urban planning wasn't just about aesthetics, but about projecting authority and controlling populations, influencing their movements and behaviors within a rigidly defined social order. Think about whose gaze this perspective catered to? Certainly not the commoners navigating those streets. Editor: Exactly. And if we look closely at the material processes, engraving as a reproductive technology made images like this widely available to elites. Consider how access to visual representations shapes our perception and reinforces social hierarchies. Curator: And what does that bird’s-eye view really do? It inherently depersonalizes. This wasn't about understanding the individual experiences of the inhabitants of Siena; it was about cataloging, surveying, owning. This distance also reminds us of the colonial gaze, this desire to document and therefore, control. The aesthetic and its production reflect the prevailing gender roles as well: artistic representation by men, usually for other men in power. Editor: True. Hollar likely used pre-existing maps, possibly augmenting them. That process of adaptation introduces its own layers of meaning. We could think of his engravings not just as faithful depictions but as objects transformed through a network of makers and commercial relationships, speaking to early capitalist consumption of cityscapes. Curator: This consumption ties back to the creation of national and regional identity. Think of how prints like this functioned as instruments of power and belonging; these are representations reinforcing what it meant to belong, who was at the center and at the margins. What sociopolitical function did cityscapes fulfil in cementing ideas about belonging? Editor: Ultimately, it's the enduring materiality that lets us probe at those past narratives. What kind of labor went into creating it, how was it sold, how does it now influence our view of cityscapes today? Curator: These considerations offer different views onto questions of identity, power, and control, reminding us that seemingly simple cityscapes actually convey dense information about the human networks that created them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.