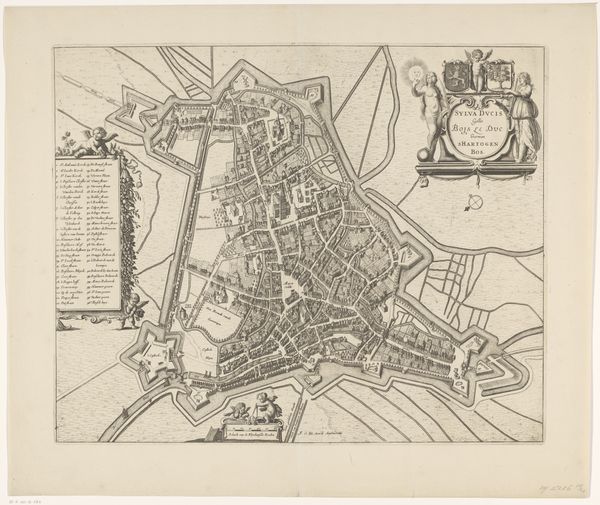

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

linocut print

#

geometric

#

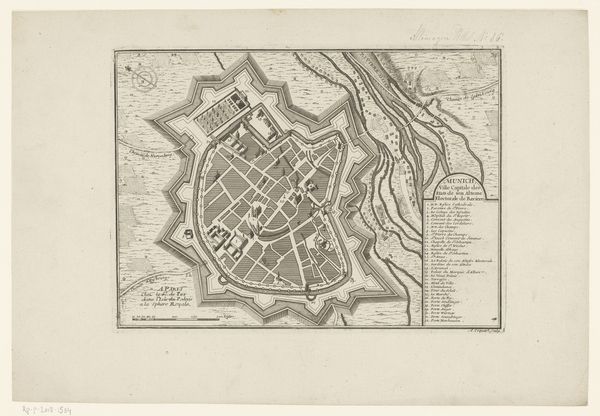

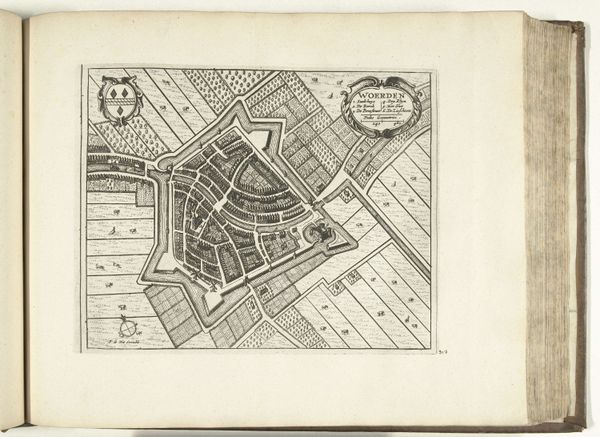

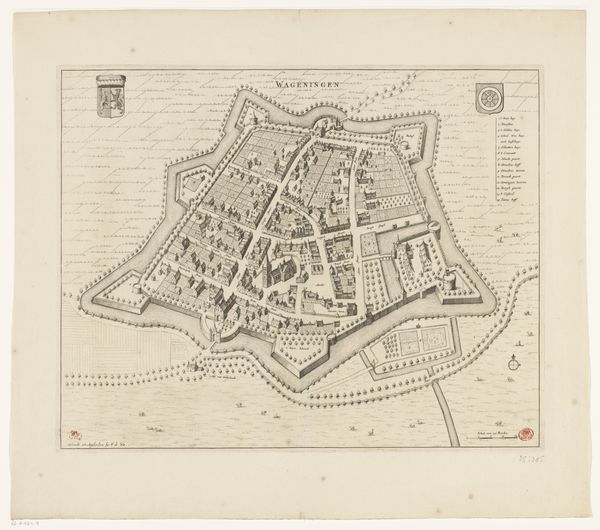

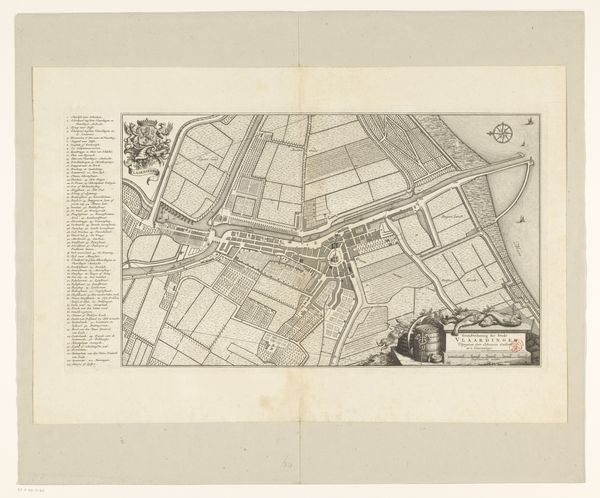

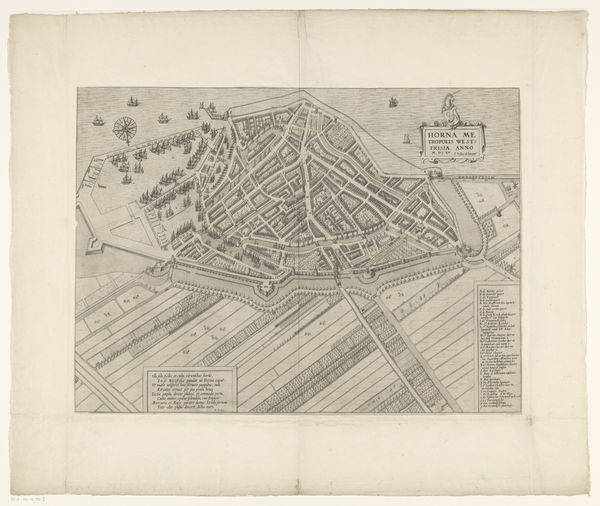

cityscape

Dimensions: height 387 mm, width 503 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

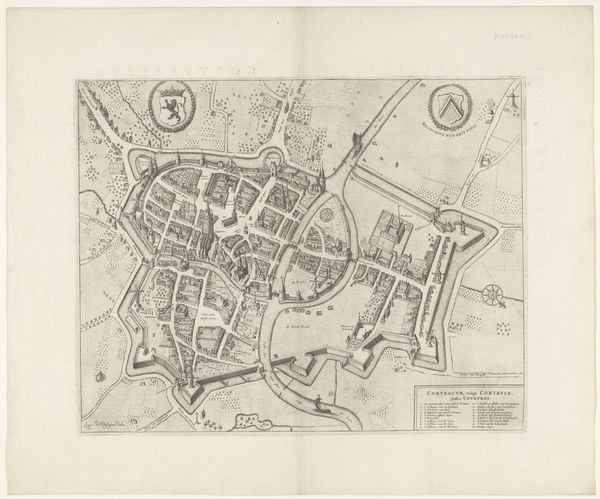

Curator: Take a moment to observe "Plattegrond van Brielle," an intriguing drawing, etching and print from around 1649 to 1728. It's currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. My initial impression is almost maze-like, all swirling streets captured in muted tones; there's an undeniable beauty in the order that almost transcends functionality. Editor: You know, it’s interesting how cartography walks that line between art and information. This isn't just a map; it's a symbolic representation, almost a declaration of civic identity. Consider how city plans throughout history, intentionally or not, embody a place's self-image, its power dynamics etched into urban design. What feeling do these geometric forms conjure in you? Curator: A quiet hum, honestly, like the concentrated potential of a sleeping giant. Those carefully rendered garden plots, those formidable walls – they whisper tales of life lived within a structured world. It's organized chaos in a way, because, despite its apparent order, you know that day to day living doesn't lend itself to the clean lines represented here. There is an order here, but an abstracted one, I imagine. Editor: I agree; the rigid forms tell one story, while the details suggest another, messier truth. Those garden plots aren’t merely decorative, nor do they simply depict the agricultural land; they're potent symbols of cultivation, control, and, importantly, prosperity. It is not uncommon for a city of any importance to project its own significance via city plans like this one. It suggests this city, Brielle, has reached a certain threshold and can afford to present this kind of image to the outside world. The symbolism creates, in essence, its own iconography. Curator: Do you think, by looking at its symbolic meaning, one can separate it from a purely historical context? After all, cartography as a practice evolves, its purpose is always changing, but perhaps its role as civic and cultural display always remains constant. Editor: Perhaps not *entirely*. We, as viewers today, imbue it with modern context; the key is how it resonates through changing times. The drawing whispers historical specifics and shouts universal symbolism, reminding us how even utilitarian designs mirror and mold culture. Curator: In the end, whether considered as art, a diagram, or as symbolic narrative, one walks away with something lasting from this etched "Plattegrond van Brielle," wouldn't you say?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.