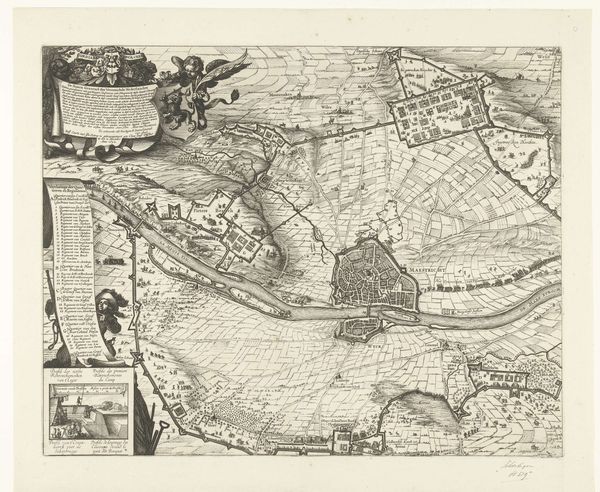

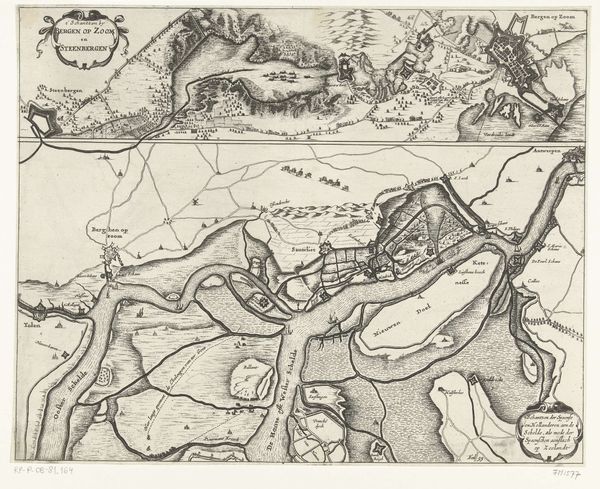

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

ink

#

geometric

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 305 mm, width 390 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

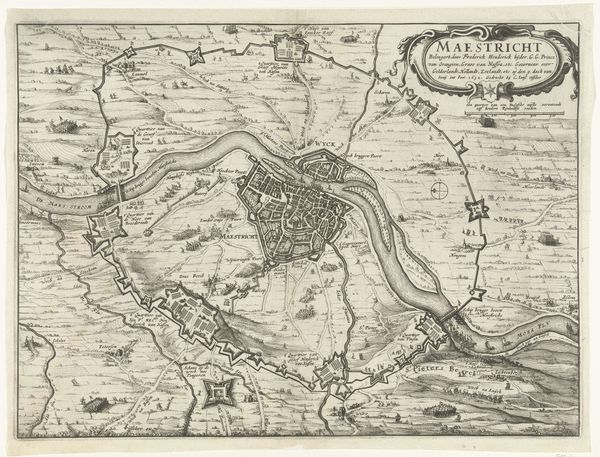

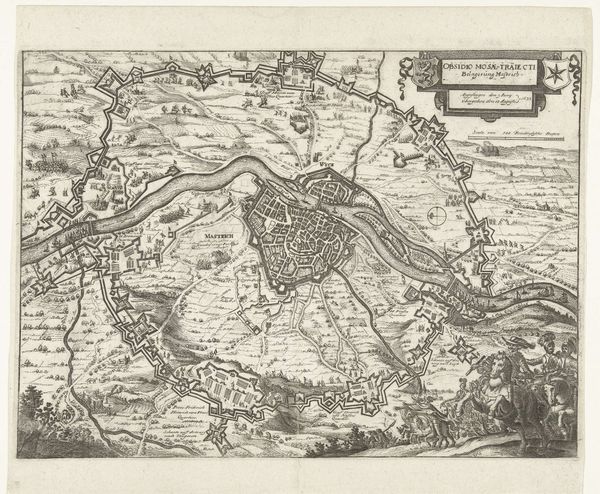

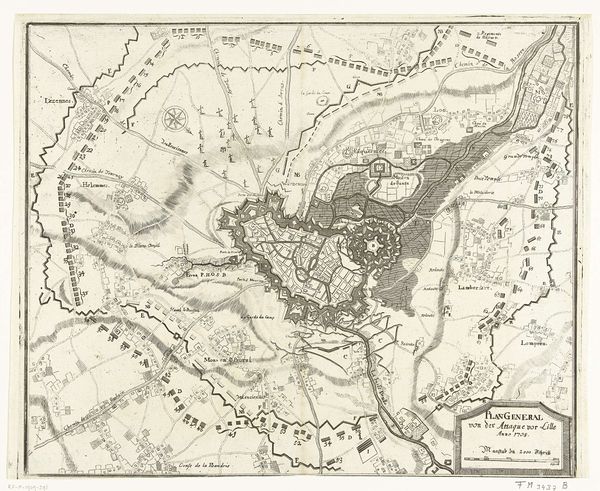

Curator: At the Rijksmuseum we have a fascinating etching titled "Maastricht belegerd door Frederik Hendrik, 1632," documenting the siege of Maastricht. Editor: Wow, it's almost aggressively detailed, isn’t it? An incredibly ornate bird's-eye view. I’m immediately struck by the geometric shapes fencing in the city. They feel so absolute. Curator: Those geometric shapes are earthworks and fortifications. What you’re seeing isn’t just a landscape, it’s a portrait of war as an engineering project, frozen in time. This was created during the Dutch Golden Age. It reflects the Republic's military ambition as it challenged Spanish control. The siege itself was a key moment in the Eighty Years’ War, wasn't it? Editor: Absolutely. Think of the impact that sort of meticulous imagery had. Seeing how the land was manipulated, controlled—warfare rendered as clean lines and angles. It suggests an almost… clinical approach to conquest. Like an architectural plan for dominance. The image also carries some darkness and the way people were trying to portray how glorious a war can be. It has nothing of that; this portrays the city being cornered like some sort of prey. Curator: And don't forget the political dimension. These prints weren't just documentary; they were propaganda, weren’t they? They presented a vision of Dutch power, competence and technical mastery. This image celebrates Prince Frederick Henry's leadership, reinforcing the image of a strong, unified Dutch Republic. Editor: Makes you wonder how many people at the time actually grasped the mechanics of it all, you know? Like, "Oh yes, those neat little pointy bits! Clearly, this is how we win wars!" I mean, maybe it reassured them. War as understandable and inevitable like mathematics or the tides. Curator: Precisely. The Dutch Golden Age wasn't just about art; it was about crafting a national identity. Images like this, endlessly reproduced and distributed, contributed to a shared sense of purpose. It's like a proto-news report, stylized and heroic. Editor: You're right, it is propaganda. Yet, despite its clear political function, there’s still a striking quality about its detail and sheer effort to reproduce such level of precision. Curator: Absolutely. It’s that tension between the cold, calculated depiction of military strategy and the underlying human cost. Editor: A complex statement indeed. I'll never see war the same after reflecting over that bird's eye view. Curator: That's the enduring power of art; challenging perceptions across the centuries.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.