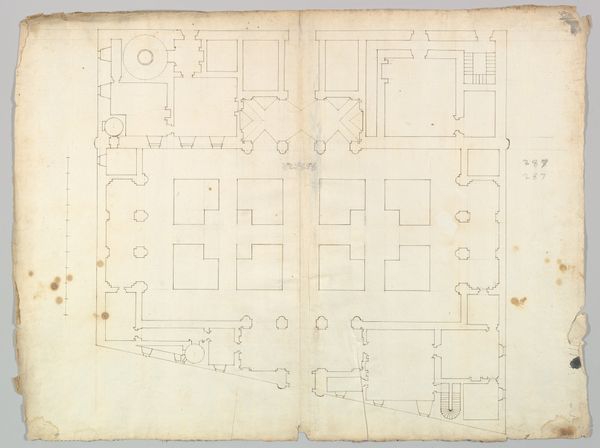

drawing, ink, color-on-paper, pen

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

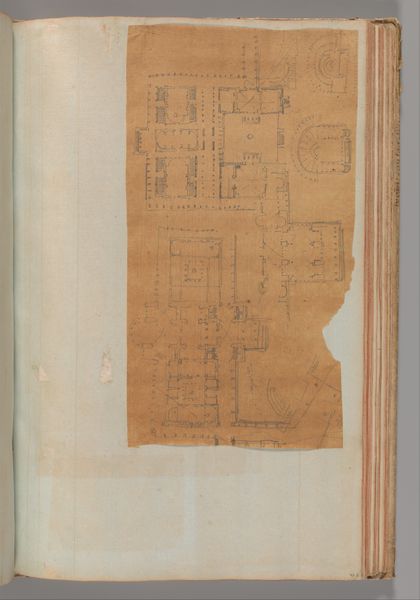

book

#

asian-art

#

sketch book

#

japan

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

color-on-paper

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen and pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

calligraphy

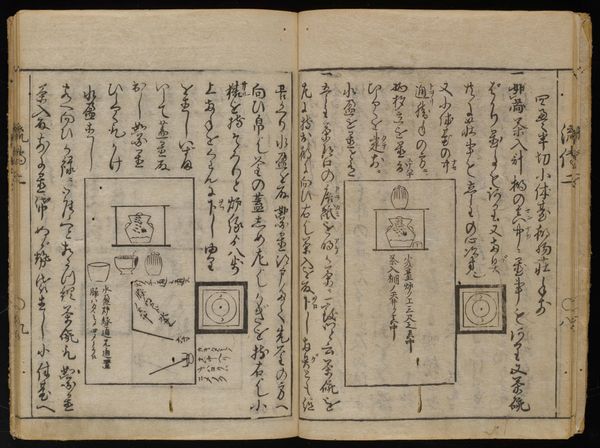

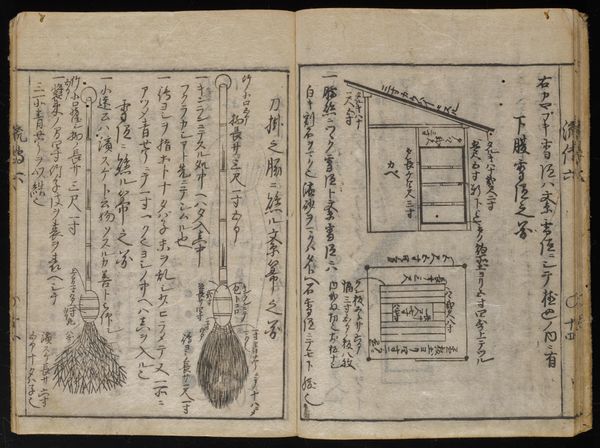

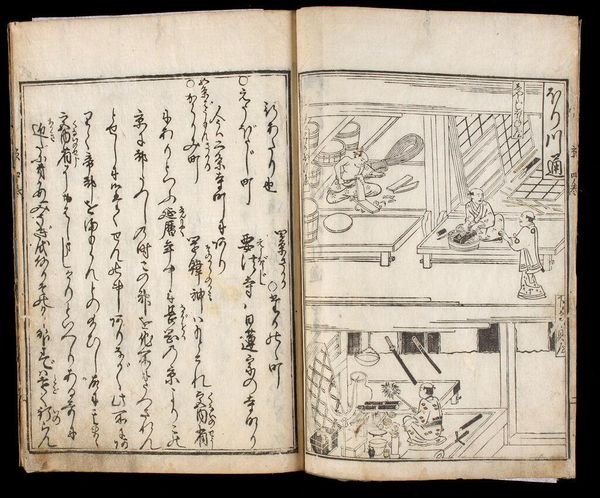

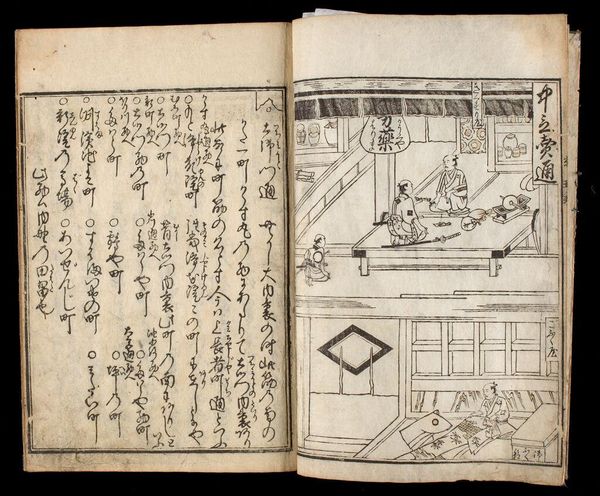

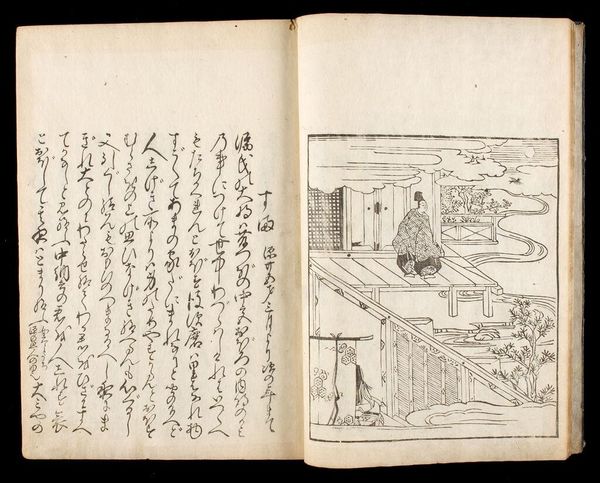

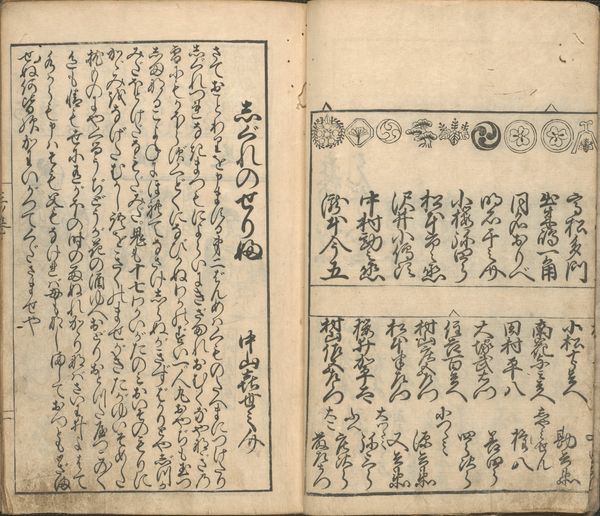

Dimensions: 8 3/4 × 6 5/16 × 1/2 in. (22.23 × 16.03 × 1.27 cm) (this volume)8 7/8 × 6 3/4 × 2 1/16 in. (22.54 × 17.15 × 5.24 cm) (all volumes inside case)

Copyright: Public Domain

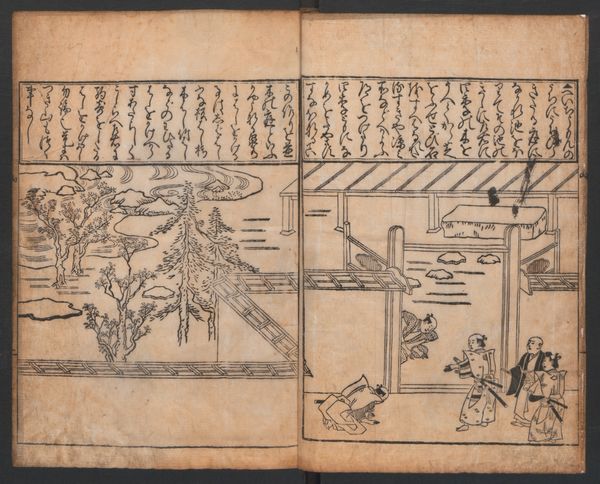

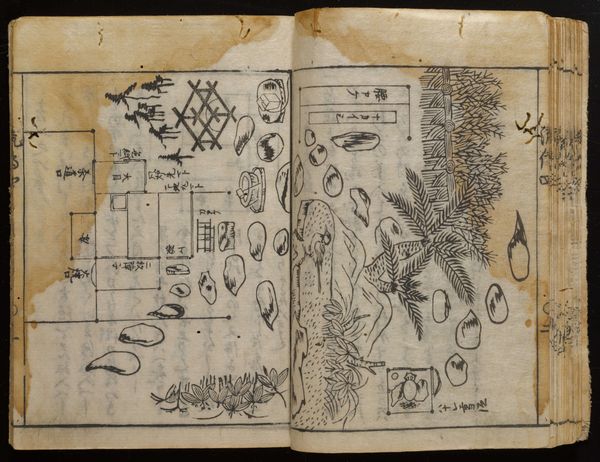

Editor: So, this is "Promulgation of the Contemporary Tea Ceremony" by Endō Genkan, made in 1694. It's a drawing, ink and color on paper. The layout reminds me of architectural plans. What strikes you when you look at this piece? Curator: What I see is a glimpse into the codification, perhaps even the commercialization, of cultural practices. The tea ceremony, laden with ritual and performative elements linked to status, becomes something to be documented, reproduced, and thus, commodified. Do you notice how the drawing is presented like a blueprint? Editor: Yes, like an instruction manual almost. It's less about the artistry and more about the "correct" way to perform a tea ceremony? Curator: Precisely. It invites us to question the power structures embedded within artistic traditions and their intersection with societal norms. Consider the context: the Edo period with its strict social hierarchies. How does the standardization of the tea ceremony play into solidifying those hierarchies? Is this a form of cultural control? Editor: I hadn’t thought of it that way, but it makes sense. Standardizing something allows those in power to define it and control who has access. Curator: Exactly! Art isn't created in a vacuum. This work shows us how cultural practices can become tools, shaping identity and perpetuating specific power dynamics. Understanding this work is key for us to reimagine how art and identity work together. Editor: I see that now. I will remember to view the artworks within the context of social constructs and intersectional paradigms that help us question pre-established ideas. Curator: And how art reflects life back to us, reshaped.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

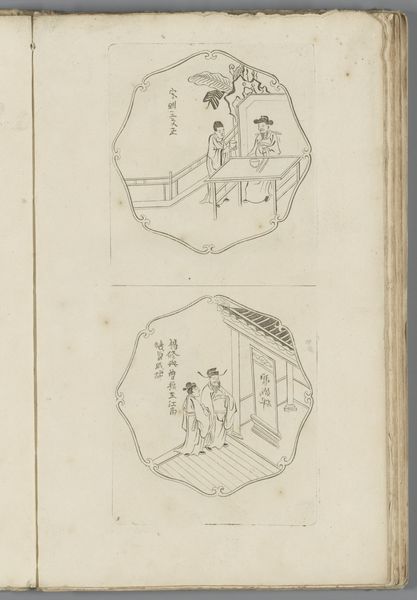

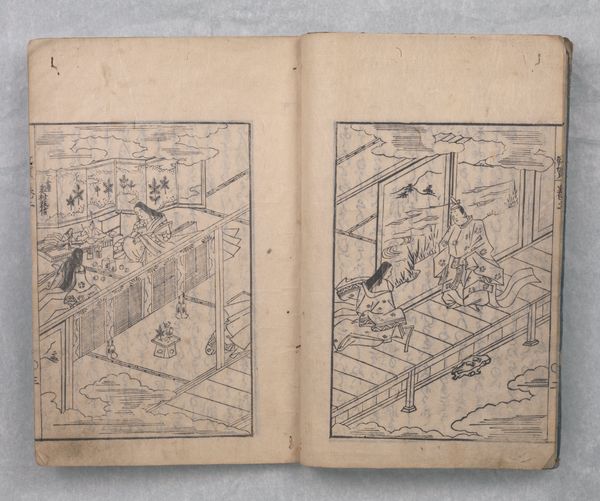

Contemporary guide to tea ceremony, Enshū school. In the mid-1600s, an aristocrat named Kobori Enshū (1579–1647), who was also a skilled poet, artist, flower arranger, and tea master, developed his own style of the tea ceremony based on the aesthetic ideal of kirei-sabi, which combined the notions of refined beauty (kirei) and patina, the wear associated with age (sabi). Enshū’s kirei-sabi style, which partially supplanted wabi (imperfect or rustic) as the dominant aesthetic, had a great impact on the design of gardens and teahouses, decoration of teahouse interiors, and the production of tea wares in the mid-1600s. Two generations later, Endō Genkan, an adherent of the Enshū School of tea, wrote a number of important books on the Japanese tea ceremony including the volumes displayed here, which sought to disseminate Enshū’s kirei-sabi tea aesthetic.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.