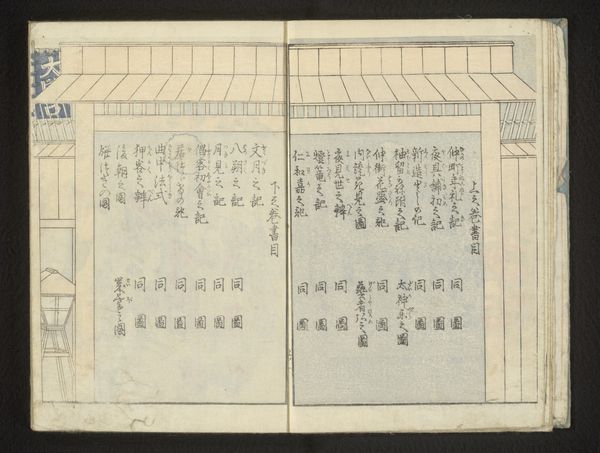

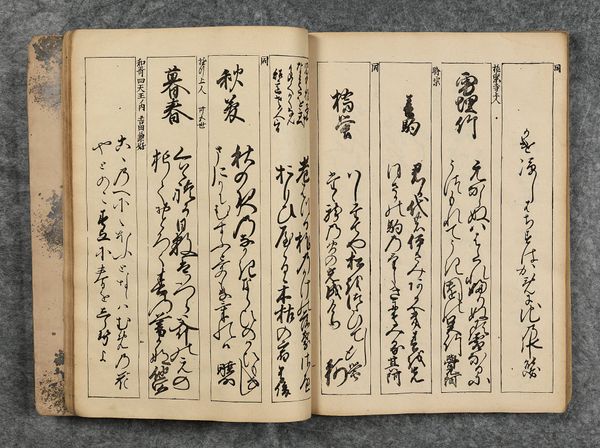

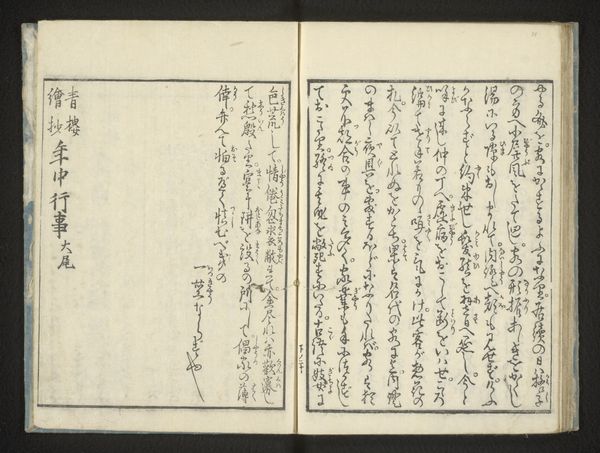

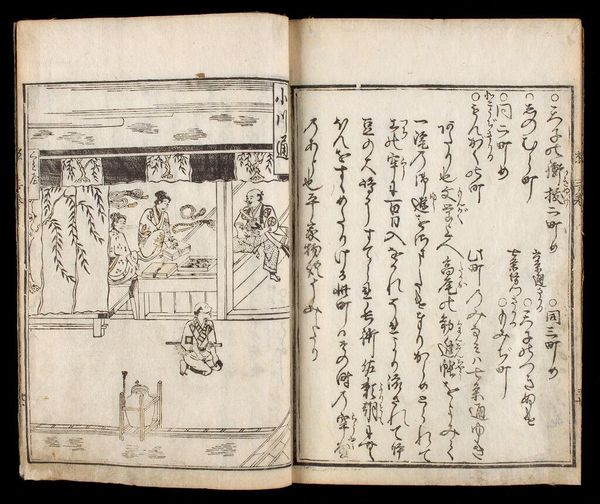

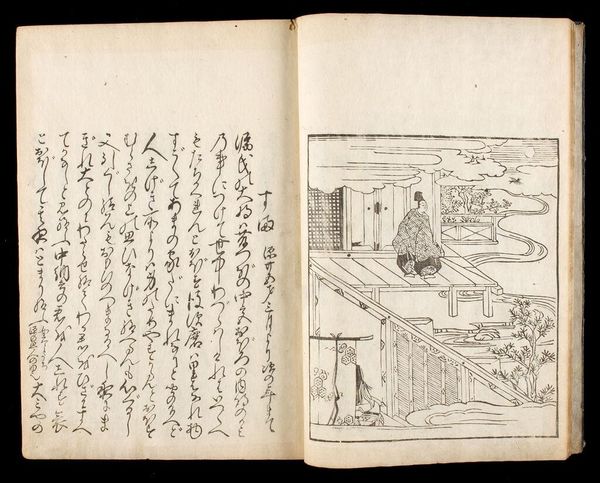

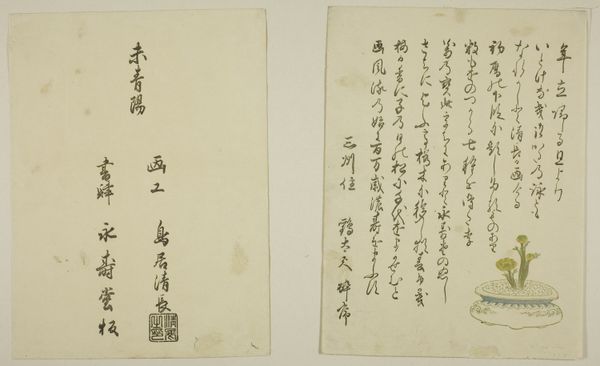

drawing, paper, ink, color-on-paper

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

japan

#

paper

#

ink

#

color-on-paper

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

pen-ink sketch

#

genre-painting

#

miniature

#

calligraphy

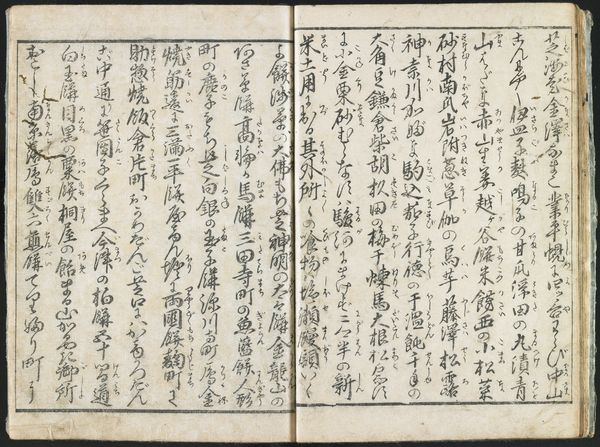

Dimensions: 8 3/4 × 6 3/8 × 5/16 in. (22.23 × 16.19 × 0.79 cm)8 7/8 × 6 3/4 × 2 1/16 in. (22.54 × 17.15 × 5.24 cm) (all volumes inside case)

Copyright: Public Domain

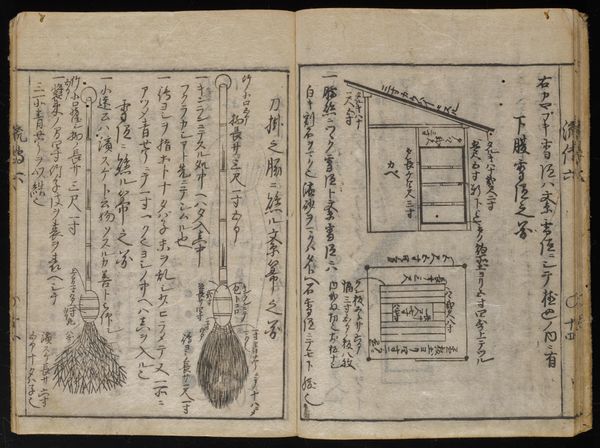

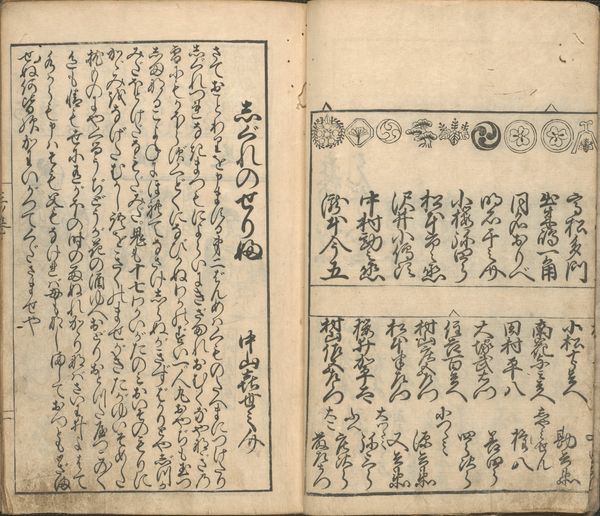

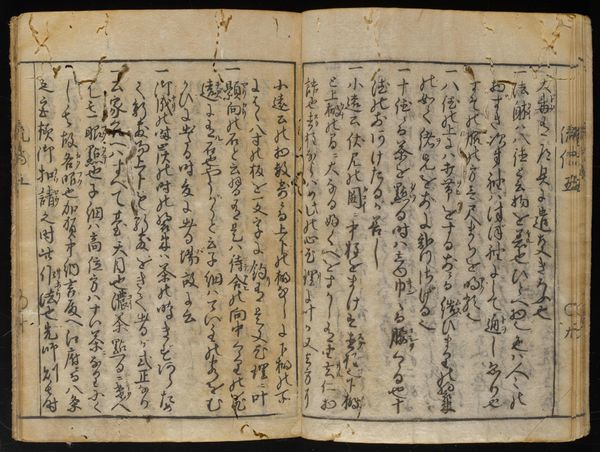

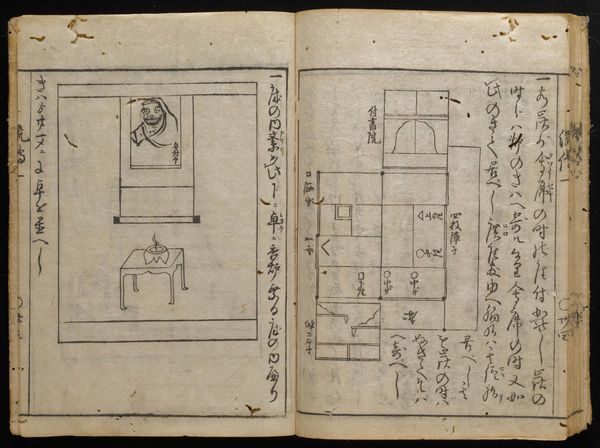

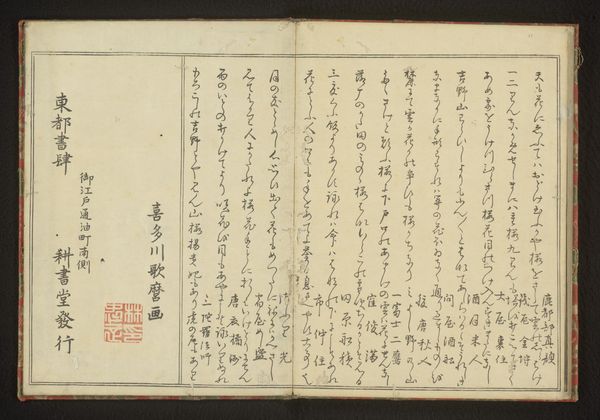

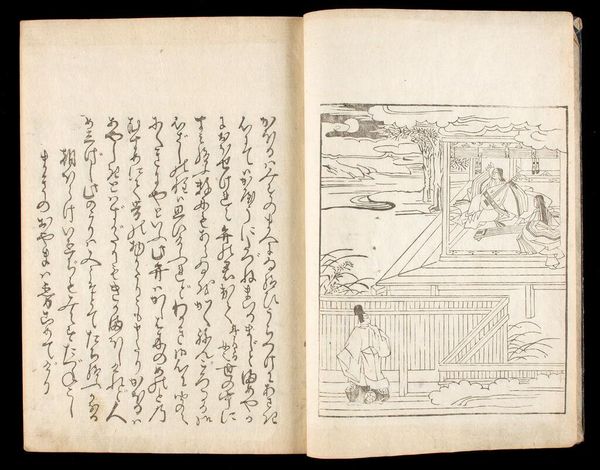

Editor: This is "Promulgation of the Contemporary Tea Ceremony" by Endō Genkan, dating back to 1694. It’s ink and color on paper, part of a book. I find the density of information fascinating, yet intimidating. What's your take on it? Curator: I see a powerful commentary on accessibility and cultural preservation. Here we have what appears to be instructions on tea ceremony, but framed within a socio-political context. Who has access to these traditions? How are they disseminated, and what power dynamics are at play when someone chooses to document or 'promulgate' them? Editor: That’s an angle I hadn’t considered. I was just focusing on the individual diagrams. Curator: Look closer. Is this really just a manual? Or is it a subversive act of democratizing a potentially exclusive practice? What does it mean to put something so refined, perhaps even secretive, into a form reproducible for the masses? Consider who traditionally controlled access to knowledge and ritual during this era in Japan. Editor: So you're saying it could be seen as a challenge to established social hierarchies? Curator: Precisely. How can artistic, social and ritual expressions democratize art and practices for all? It uses a seemingly benign subject—tea—as a vehicle. Can this also reflect larger themes of social progress? Editor: Wow. I initially saw just a quaint instructional guide. Now I see a potentially radical statement about who gets to participate in cultural traditions. Curator: Exactly! Thinking about art as intertwined with these issues helps uncover many fascinating layers!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Contemporary guide to tea ceremony, Enshū school. In the mid-1600s, an aristocrat named Kobori Enshū (1579–1647), who was also a skilled poet, artist, flower arranger, and tea master, developed his own style of the tea ceremony based on the aesthetic ideal of kirei-sabi, which combined the notions of refined beauty (kirei) and patina, the wear associated with age (sabi). Enshū’s kirei-sabi style, which partially supplanted wabi (imperfect or rustic) as the dominant aesthetic, had a great impact on the design of gardens and teahouses, decoration of teahouse interiors, and the production of tea wares in the mid-1600s. Two generations later, Endō Genkan, an adherent of the Enshū School of tea, wrote a number of important books on the Japanese tea ceremony including the volumes displayed here, which sought to disseminate Enshū’s kirei-sabi tea aesthetic.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.