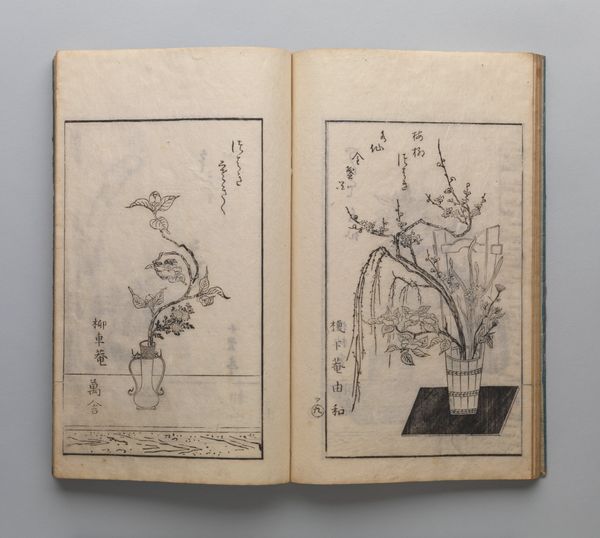

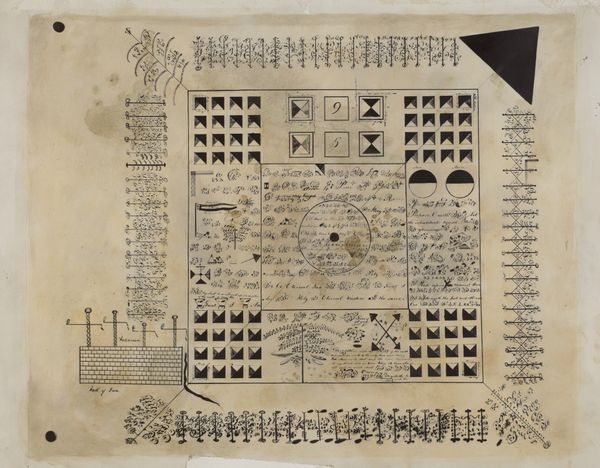

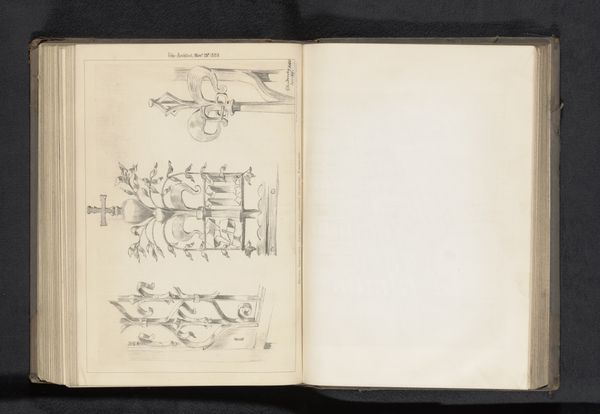

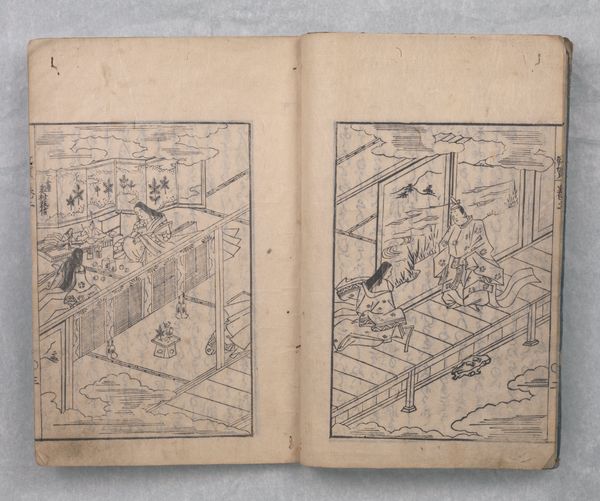

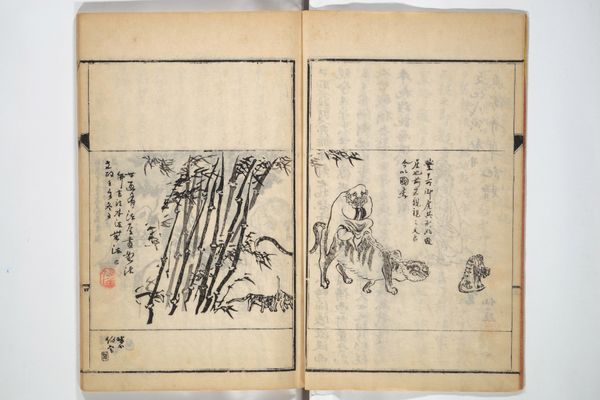

drawing, paper, ink, color-on-paper

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

pen sketch

#

book

#

asian-art

#

sketch book

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

color-on-paper

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: 8 3/4 × 6 3/8 × 3/4 in. (22.23 × 16.19 × 1.91 cm)8 7/8 × 6 3/4 × 2 1/16 in. (22.54 × 17.15 × 5.24 cm) (all volumes with case)

Copyright: Public Domain

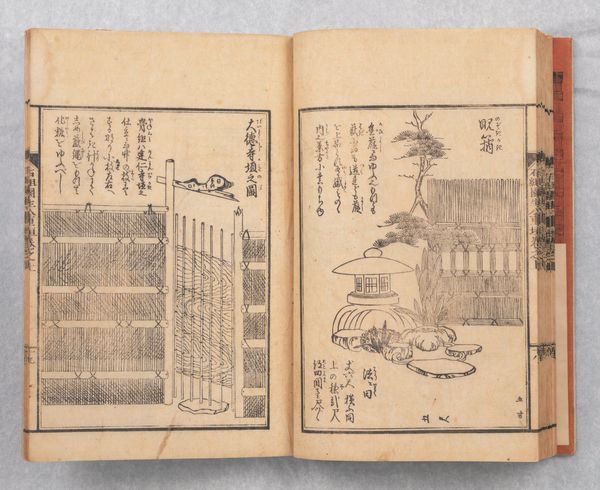

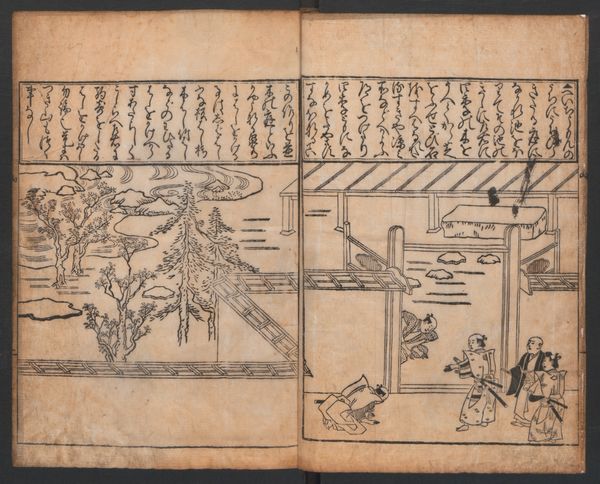

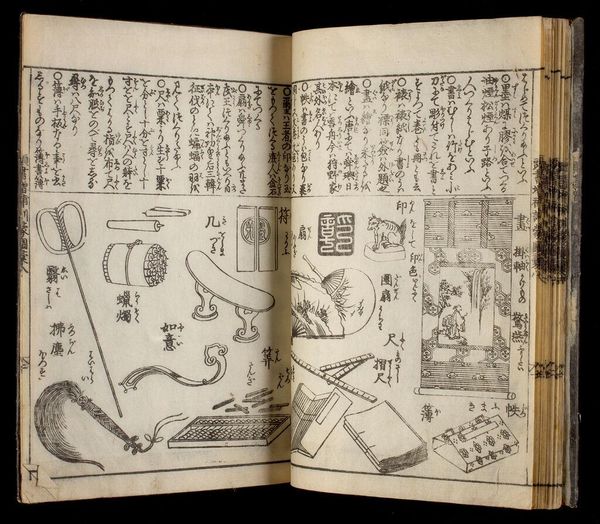

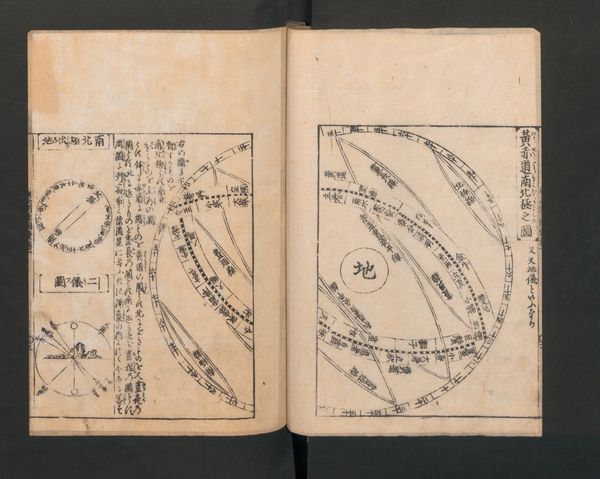

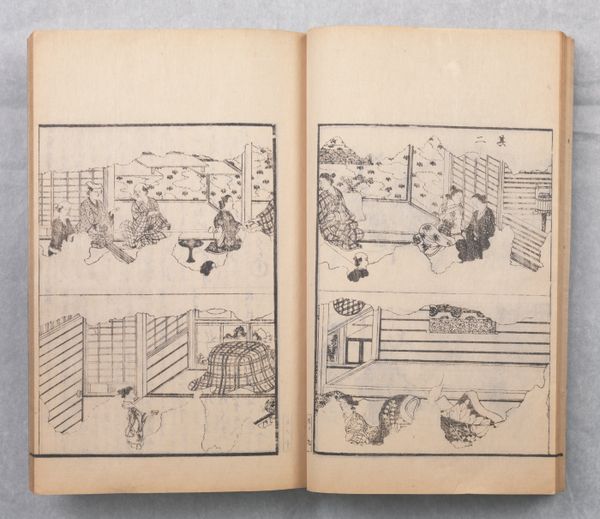

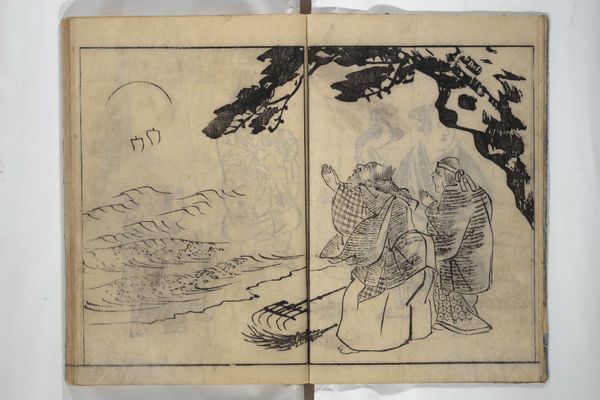

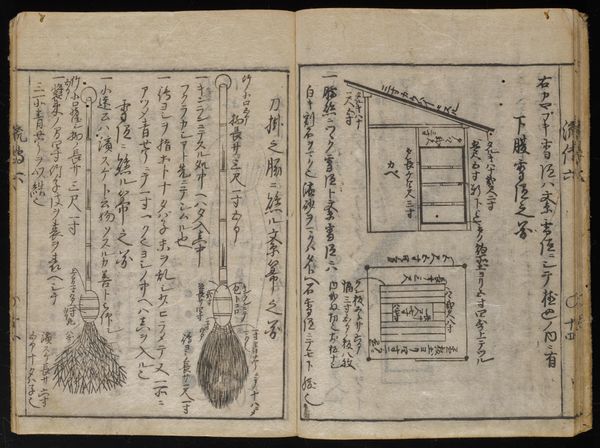

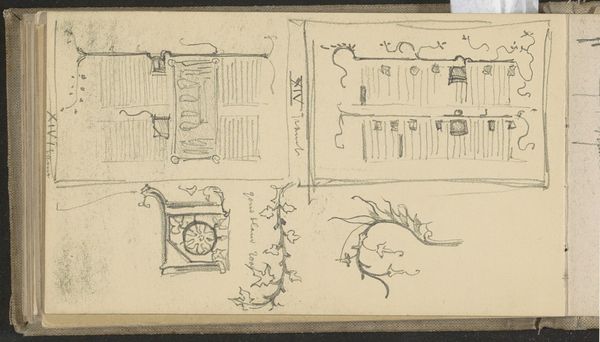

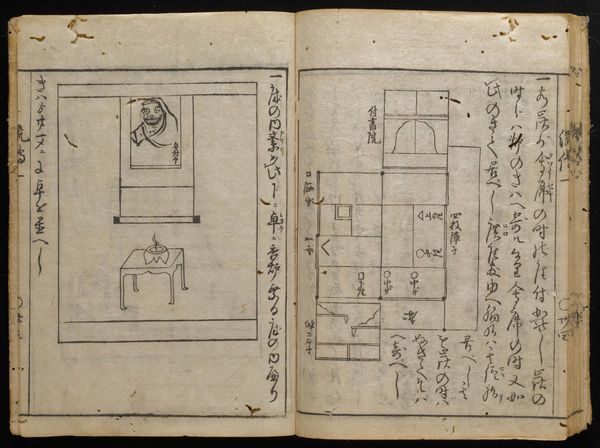

Curator: The artwork before us, “Promulgation of the Contemporary Tea Ceremony,” created in 1694 by Endō Genkan, offers a fascinating look into the aesthetics and practices of its time. What do you notice first? Editor: The immediacy. The quick, almost frenetic linework, combined with the aged paper creates an impression of something very intimate, like a personal sketchbook. There’s an interesting dance between the structured elements, like the grid on the left page, and more organic shapes on the right. Curator: Exactly. These personal sketchbooks or "ukiyo-e" as they were sometimes called, served not just as records but also as tools to popularize cultural practices. In this case, the evolving tea ceremony. Editor: It seems as though we’re seeing instructions laid bare. The architectural drawing of the tea house and the scattering of forms remind me of a sort of exploded diagram, where the viewer is meant to piece together the components. Curator: Yes, it's both documentation and perhaps a mnemonic aid for those learning the nuances of the ceremony. It also offers a glimpse into the social currency of tea at that moment in Japan. A ritual undergoing constant revision and reinterpretation to stay relevant. Editor: You can also see it on the material level; it’s a rather casual deployment of line to create texture. There's a rawness to the sketchbook that I appreciate. Curator: Agreed, its power comes from how the spontaneity captures a moment in time, the culture shifts occurring when Endō Genkan made it. Editor: This sketchwork feels so alive. Curator: It gives us insight into the cultural and societal weight that something as simple as tea could carry. Editor: Indeed, an excellent marriage of function and aesthetics.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Contemporary guide to tea ceremony, Enshū school. In the mid-1600s, an aristocrat named Kobori Enshū (1579–1647), who was also a skilled poet, artist, flower arranger, and tea master, developed his own style of the tea ceremony based on the aesthetic ideal of kirei-sabi, which combined the notions of refined beauty (kirei) and patina, the wear associated with age (sabi). Enshū’s kirei-sabi style, which partially supplanted wabi (imperfect or rustic) as the dominant aesthetic, had a great impact on the design of gardens and teahouses, decoration of teahouse interiors, and the production of tea wares in the mid-1600s. Two generations later, Endō Genkan, an adherent of the Enshū School of tea, wrote a number of important books on the Japanese tea ceremony including the volumes displayed here, which sought to disseminate Enshū’s kirei-sabi tea aesthetic.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.