drawing, paper, pen

#

drawing

#

map drawing

#

landscape

#

paper

#

architectural drawing

#

pen work

#

pen

#

genre-painting

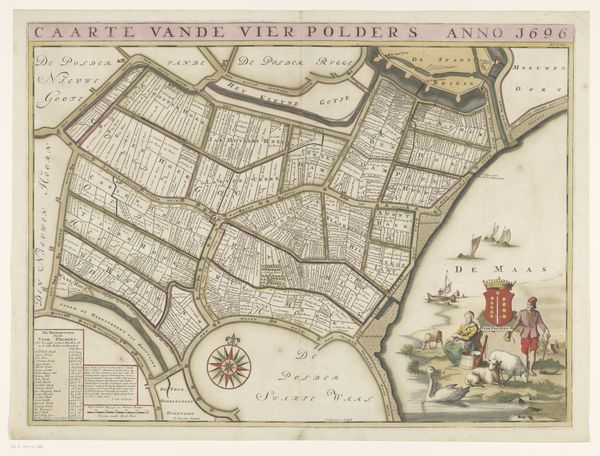

Dimensions: height 496 mm, width 705 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

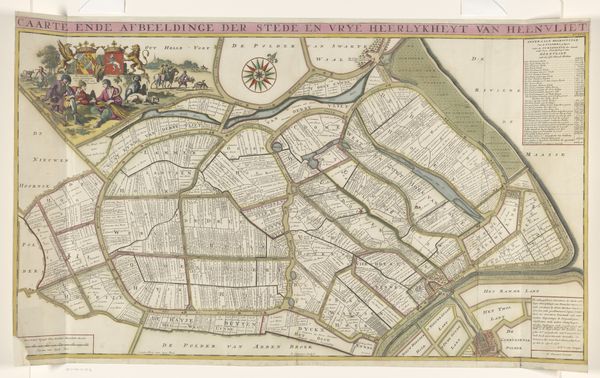

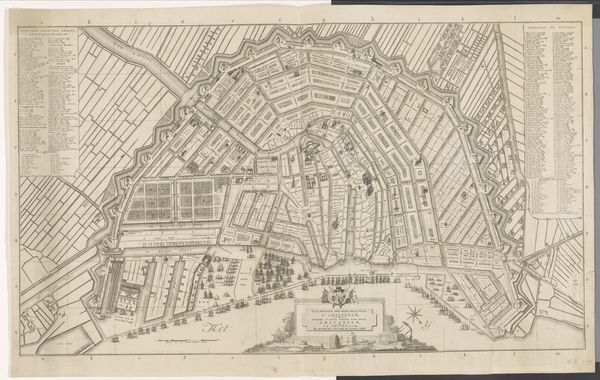

Curator: Here we have “Kaart van de Sint-Cornelispolder (Quackpolder),” created between 1701 and 1729. It's a drawing rendered in pen on paper by Jan Stemmers. Editor: My first impression? Order! An idealized vision. The landscape here, though presented as a functional map, feels almost meticulously composed, almost sterile. Curator: Maps like this weren't just about navigation; they were assertions of control. Consider the social implications of land ownership reflected in this genre painting: Who held power, who labored, and who was excluded from the narrative being created here? Editor: Absolutely, but let's focus on the “how.” Look at the density of pen strokes; that's laborious! The material process reflects the intense management of the land itself. Canals, plots, even the script—all point to imposed order, human labor wrestling with nature. Curator: Indeed. Notice how the perspective flattens, turning land into property to be surveyed and distributed. Who benefits from such “rationalization” of space? Land ownership and power dynamics during this era determined access to resources. And what were the potential impacts for displaced communities or exploited workers? Editor: The very act of drawing this map changed the polder. Creating divisions and enabling administration reshaped the landscape. Pen, ink, and paper weren’t passive recording devices, but active tools in reshaping territory. The small figures in the upper right serve as stakeholders literally watching over all the agricultural resources! Curator: And in the way land becomes quantified, measured, and claimed, we can discern power structures at play. Who gets to define and claim ownership? Editor: It's easy to overlook the artifice in a seemingly utilitarian object, but Jan Stemmers offers insight into the means and motivations behind that process. Curator: So next time, perhaps ask not just, "what does this represent," but "who decided that? And who was erased?" Editor: Maps speak, but what about what is suppressed during their construction? Worth considering indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.