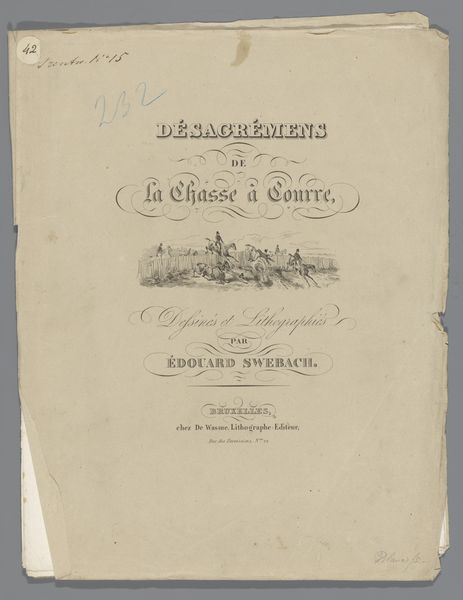

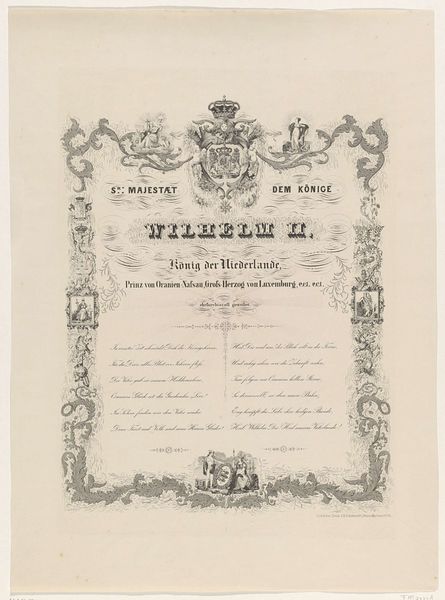

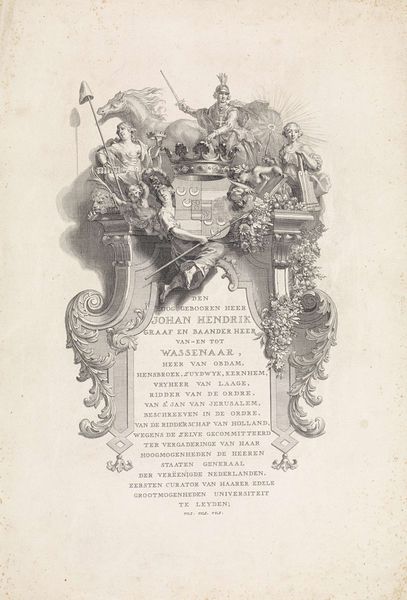

drawing, print, etching, paper, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

pencil work

#

engraving

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 630 mm, width 468 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, I see solemnity. The sharp contrast in the etching gives King Willem I Frederick a rather imposing presence, doesn’t it? Editor: It does. And this engraving, "Portret van Willem I Frederik, koning der Nederlanden," likely dating to 1830 or 1831, really is a product of its time, when new printing technologies and royal imagery intertwined to cultivate a sense of national identity. Curator: You’re right. The symbolism surrounding him—the crown, the implied military accolades—it all contributes to the construction of power. But look closer at the typography; notice the almost calligraphic quality, especially in the phrases of "Homage" and "Respect" that feel like they are physically surrounding his portrait, like a protective embrace? Editor: Indeed. It speaks to the explicit intention to instill public faith during a period of significant political upheaval and shifts in power dynamics. One wonders about its reception, if audiences interpreted these images as sincere expressions of devotion, or carefully crafted propaganda. Curator: It's more than just devotion; it's almost a plea for affection, isn’t it? Phrases like “Homage D’Amour" and the mention of “Devouement” hints at this. How deeply connected a leader needed to be to the hearts and minds of the people is also conveyed by the symmetry with which such symbols and pronouncements were emblazoned into such portraiture, using specific cultural markers. Editor: I agree that such displays underscore the performative nature of power, but it's vital to see how deeply images became political tools. The choice of disseminating this likeness through mass-producible prints reflects how rulers sought direct connections with the citizenry—bypassing traditional avenues of control to manufacture popular support, especially when etched or engraved onto papers available to those outside court. Curator: To this day we can consider not only how mass produced artworks shift visual representation in culture but consider how a portrait creates lasting archetypes. In viewing it now, with our modern understanding, it serves not merely as a visual object, but as a repository of political intent, emotional desires, and enduring historical resonance. Editor: Absolutely. Examining this print offers a small but telling glimpse into how public perception was intentionally shaped in a nascent media age, inviting ongoing inquiry into the enduring symbiosis between politics and visual representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.