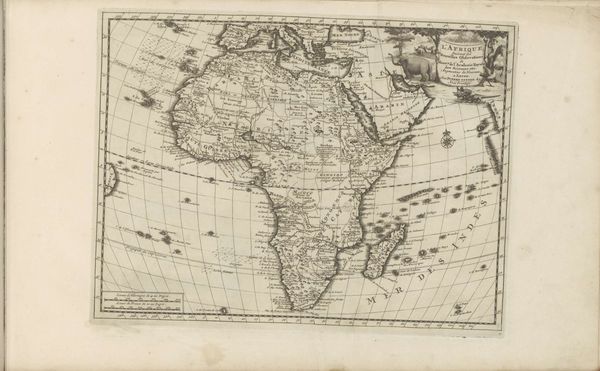

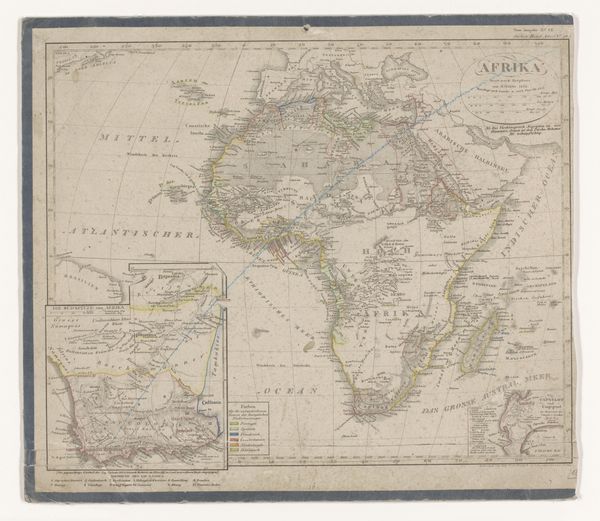

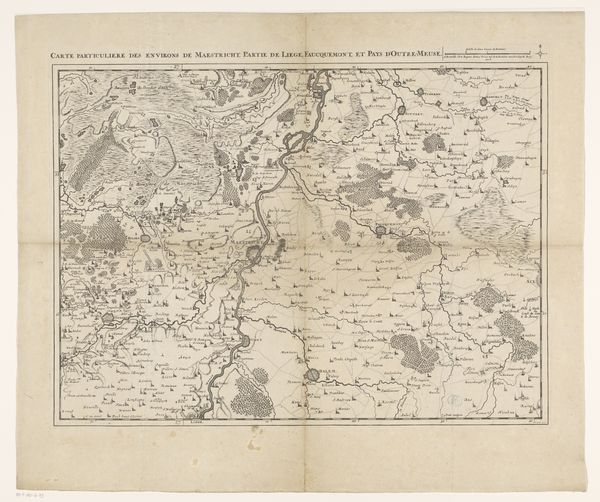

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

geometric

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 177 mm, width 212 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a rather fascinating print entitled "Kaart van Afrika," created in 1774. It's an engraving on paper, employing ink to delineate the continent's features. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: Stark, clinical even. The grid is so prominent, imposing a sense of… ownership? It’s interesting that the unknown cartographer, emphasizes the geometric structure as much as the land itself. It looks more like an act of subjugation than simply a map. Curator: Exactly! Consider the historical context: 1774. Europe was in a frenzy of colonial expansion. Maps like these were not neutral; they were tools of empire. They visually asserted control, carved up territories, and influenced political narratives back in Europe. Editor: Absolutely. Look at how different regions are labeled, or even omitted. “Negritien,” right there in big letters. This isn't just geographic data; it’s about racial categorisation and a deliberate creation of hierarchies. These labels dehumanise and justify exploitation. Where are the names of the actual people living there? Curator: This particular print likely served a didactic purpose, disseminating geographic "knowledge" – a controlled, Eurocentric view – to the European public. Note the precise coastline contrasted with the vague interior. It's reflective of where Europeans actually were along the coast, versus what they "imagined" the interior to be, all rooted in limited exploration. Editor: And it's powerful to recognise this lack of "knowledge" as deliberate ignorance. It allows the colonizers to project their own desires and narratives onto the land and people, obscuring the existing complex realities. A seemingly objective drawing actively conceals more than it reveals. Curator: Right. We should also note how the act of producing and circulating this map in Europe creates and solidifies these power dynamics. Its availability and inclusion in publications reflect what information and perspectives are privileged during this period. Editor: Precisely, what isn’t being shown is just as critical as what is. Engaging with this map today offers the ability to reclaim those silences, fill them with the stories, and actively critique these kinds of power structures that persist to the present day. Curator: Thank you for adding those dimensions, considering how maps reflect the social structures of their time challenges us to look at our contemporary geographic information with a similar critical eye. Editor: And for that, it underscores the importance of visual activism, urging us to reclaim images and confront ongoing power structures in innovative ways.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.