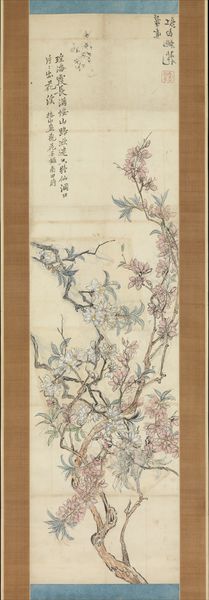

Swallow's Song in Spring Breeze Possibly 1852 - 1853

0:00

0:00

silk, ink

#

water colours

#

silk

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: 38 1/2 × 11 3/8 in. (97.79 × 28.89 cm) (image)72 1/2 × 17 1/4 in. (184.15 × 43.82 cm) (mount, without roller)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Ah, the “Swallow’s Song in Spring Breeze” hanging scroll—delicate as a sigh. Painted, we believe, by Tsubaki Chinzan around 1852 or 1853, and rendered with ink and watercolors on silk. What leaps out at you? Editor: I notice immediately how spare and vertical it is, like a musical staff waiting for notes. The color palette is so restrained it almost feels whispered—how do you see that working within the context of the artist's social milieu and choices around materials? Curator: Whispered—yes, precisely! Chinzan, in the grand tradition of Nanga painting, really saw art as an expression of personal feeling and scholarly pursuit. It's about the artist's heart speaking directly, as much poetry as representation. The delicate silk allows light to filter through, adding an almost ethereal quality to the colored-pencil work. Editor: I agree, the silk gives it a ghostly quality. You know, silk in 19th century Japan wasn't merely a backing—it was connected to intricate networks of production. So when an artist used a textile with such deep social and material roots, that itself was making a very deliberate choice about how art intersects with daily existence. Do you think this choice affected the popular reception of this work? Curator: Absolutely, the choice of materials echoes Chinzan’s wider circle of literati artists; engaging with craft elevated it to "high art". It resonates deeply because we all yearn for a breath of spring. Notice how that lone swallow brings life to the whole piece. I wonder where he's flying? What's the little guy thinking? Editor: He looks determined and efficient in his task, and that's probably key to unpacking this piece's appeal for audiences—linking it to economic shifts in the 19th century and that era's shifting class positions and ideas about craft. The bird carries a promise, as they say. I also keep noticing the nest. The raw materials from which it is made--mud, twigs, saliva--that is material engagement if I've ever seen it. Curator: I agree that the painting celebrates a material encounter and even provides insight into seasonal themes related to daily life. To me, this lovely scroll serves as a delicate bridge, where anyone may access this single moment of spring suspended on fragile silk. Editor: I will definitely agree there. Reflecting on this piece through this conversation is interesting as well. Materially and conceptually, there's a conversation happening that goes beyond spring.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Tsubaki Chinzan overcame tremendous adversity to become one of the leading Chinese-style painters in Japan in the 1800s. His father died when he was only seven, leaving him and his mother destitute. Perhaps because of their sordid living conditions, he suffered from a pulmonary disease from a young age. Nevertheless, he eventually earned the minor military rank of spear bearer and was highly skilled in martial arts. Only after the low wages of this official rank forced him to seek additional income did he become a professional artist. He studied with the renowned painter Watanabe Kazan (1793–1841), who integrated elements of Western realism into his work. Here, Chinzan’s close attention to natural detail probably reflects that influence. The light, lyrical impression created by the “boneless” method (painting forms with only ink and color washes instead of outlines) and lush color tonalities, however, reflects Chinzan's own artistic sense and consummate skill with the brush.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.