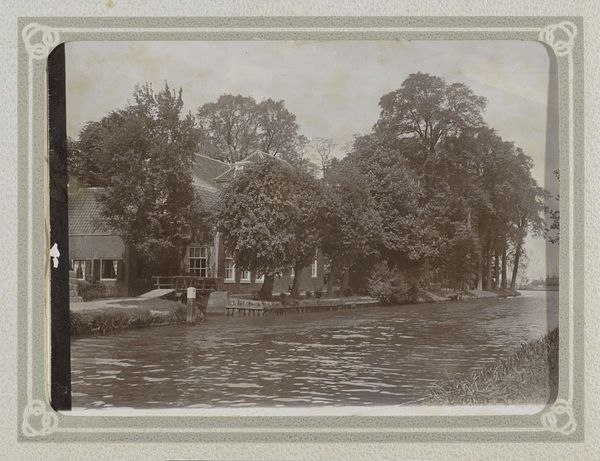

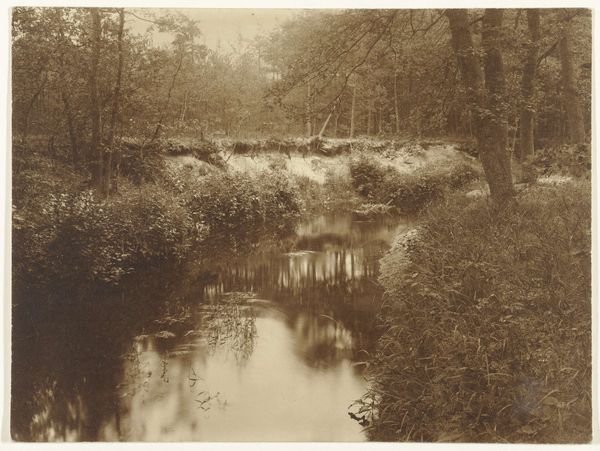

Dimensions: height 169 mm, width 227 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us is “Watermolen bij Vorden, Gelderland,” or “Watermill near Vorden, Gelderland,” a photograph taken by Richard Tepe sometime between 1900 and 1930. The Rijksmuseum is its current home. Editor: It has this wonderfully dreamlike quality, doesn't it? The whole scene seems to glow with an almost sepia-toned luminescence. You can almost smell the damp wood and moss. Curator: Indeed, it beautifully embodies the pictorialist style— an embrace of impressionism— seeking to elevate photography to the status of fine art through soft focus and evocative compositions. Tepe employed the gelatin-silver print technique, a common process that nevertheless yielded distinctive tonal effects. The watermill itself holds potent symbolism. Editor: Right, because watermills meant local power, local grain, and a circumscribed regional economy before industrialization and national distribution networks utterly transformed material culture. But the grain grinding here must be slow, old, relying upon what the river gives it. What would local labor look like at this time and how does the photograph evoke those questions? Curator: The watermill often symbolizes the cyclical nature of life, the relentless turning of time, and the power of natural resources harnessed for human needs. Water also signifies purification and renewal, deeply resonating within collective human experience, regardless of the material specifics of production and output. It speaks to both physical and spiritual sustenance. Editor: I find myself questioning the romantic vision, though. The heavy machinery here, those rough timbers, the fact of its decay -- the exploitation of the environment by human technologies, whether sustainable or not, shouldn't be elided. Tepe focuses on this spot's natural, bucolic feel, ignoring what would almost surely be tough work. Curator: Certainly, Tepe's selective focus creates a very specific narrative, one that prioritizes aesthetic harmony and timelessness. It invites us to consider the power of imagery to shape our perceptions, even subtly masking other realities. How different, I wonder, if it were a cyanotype. Editor: All those variations are crucial to remember as a contrast, even when we don't have it in front of us, when viewing photography as artifact. Still, its ability to invite introspection around these symbolic meanings and its own materiality is quite potent. Curator: Precisely, and with the material process, in this context, the choice has led us into unexpected territories and deepened the discussion significantly.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.