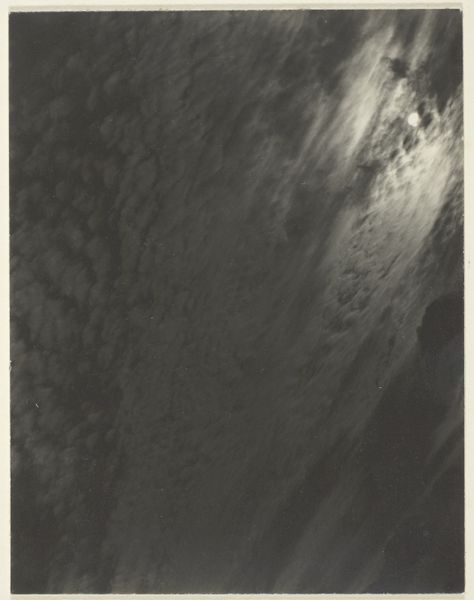

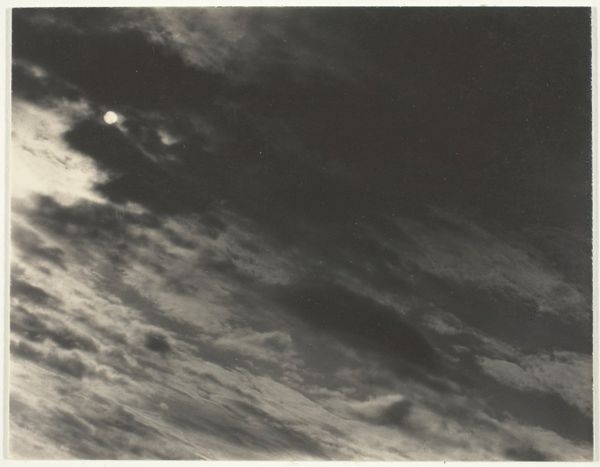

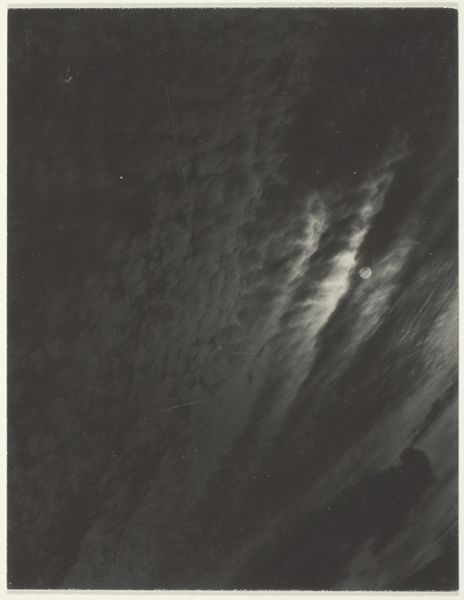

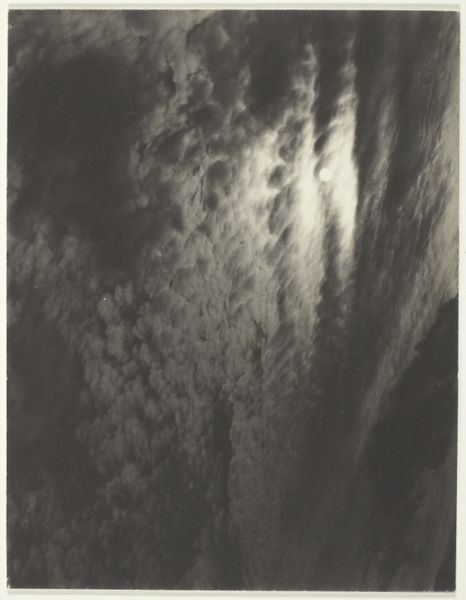

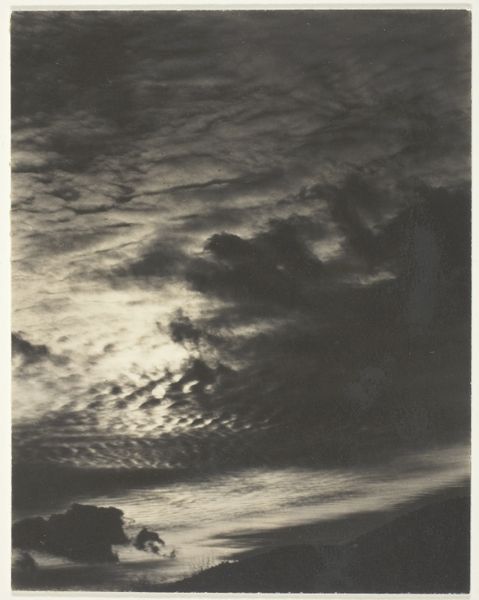

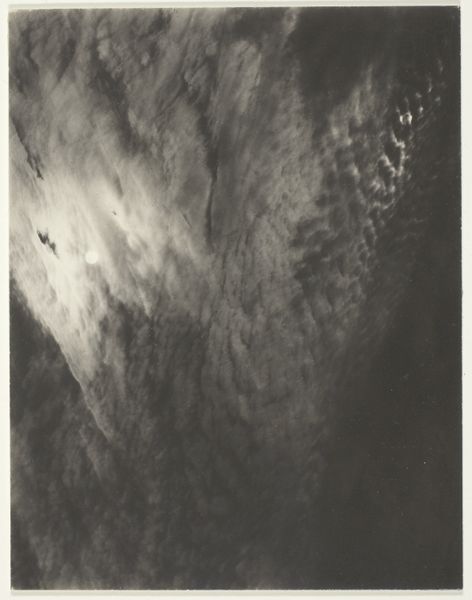

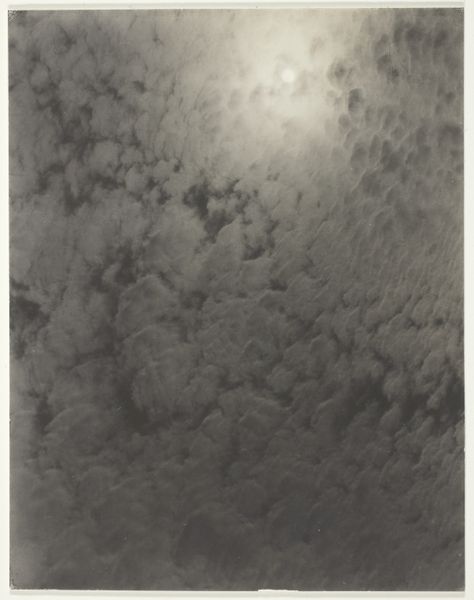

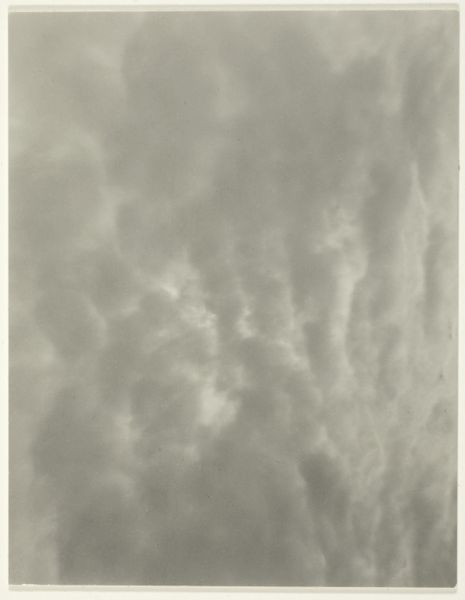

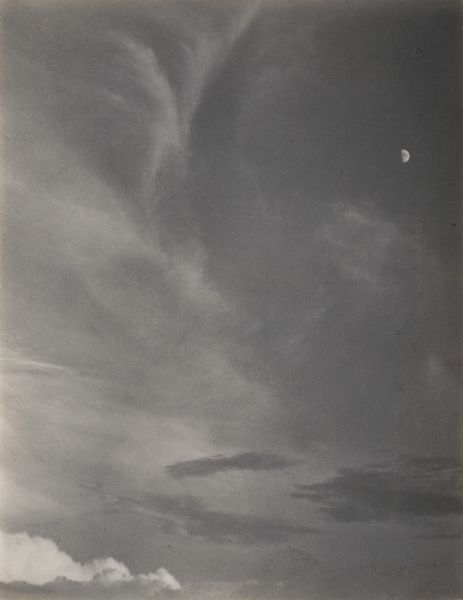

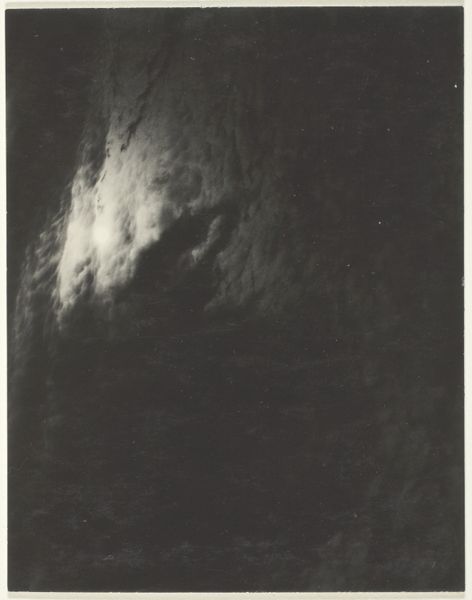

Dimensions: 11.7 × 9.2 cm (image/paper/first mount); 34.3 × 27.7 cm (second mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Alfred Stieglitz's "Equivalent, from Set E (Print 3)", taken in 1923. It's a black and white photograph on paper, and I’m struck by how modern and abstract it feels. What’s your take on this seemingly simple cloudscape? Curator: It's anything but simple! Stieglitz's Equivalents are a crucial challenge to understanding photography as mere representation. Consider the cultural context: by the 1920s, photography was striving for acceptance as fine art. Stieglitz, through his gallery "291," fiercely advocated for that recognition. Editor: So, these cloud photos were a kind of argument? Curator: Precisely! He deliberately chose clouds – something universally familiar, yet infinitely variable. This series was created after ceasing from taking portraits of Georgia O' Keeffe, his then wife. By photographing clouds he was using an accessible, and arguably neutral, subject to represent the depths of human emotion and experience. Are the photographs truly neutral when knowing his artistic direction shifted after his change in personal circumstances? What did Stieglitz really seek to do? Editor: That makes sense. It detaches the photograph from simply documenting reality, right? Curator: Exactly. Stieglitz sought to demonstrate photography's capacity for abstraction, pushing beyond literal representation. These Equivalents are metaphors, aiming to evoke emotional responses independent of their subject matter. By disassociating photography from its traditional documentary role, Stieglitz opened space for explorations of form and subjective interpretation within the medium. Think about the impact this had on future generations of photographers and conceptual artists. Editor: I see. So, in a way, he democratized photography by removing the need for a grand subject? Curator: Precisely! He took what’s freely available – the sky - and challenged our preconceived notions of art and subject matter. He transformed an everyday phenomenon into a vehicle for universal expression, using it to probe how photography participates in socio-political discourse on image consumption. What do you think Stieglitz hoped to do with this particular series and how would this work be different in contemporary society? Editor: It's fascinating to consider how something so seemingly simple could be so revolutionary. Curator: And how its ripples continue to shape our understanding of art today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.