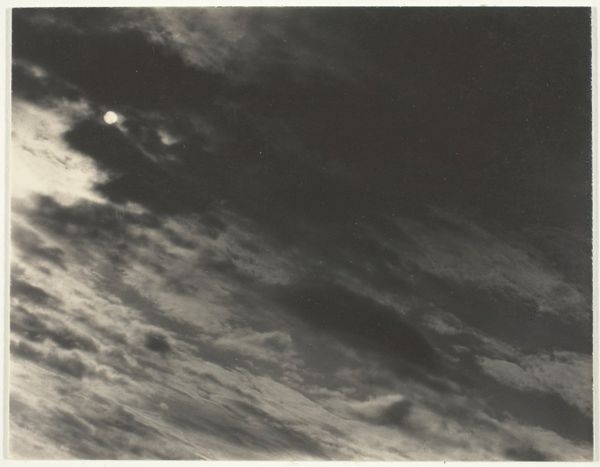

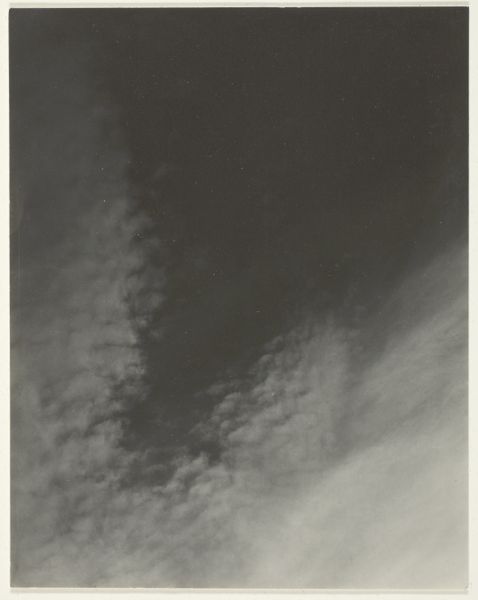

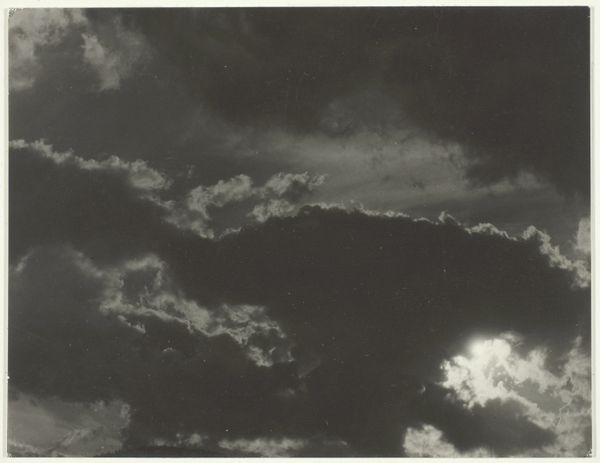

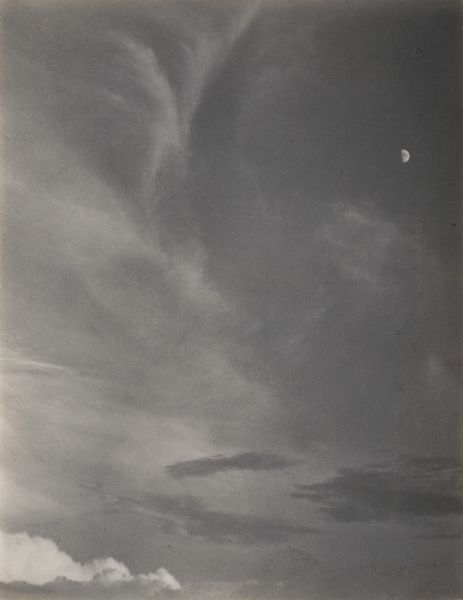

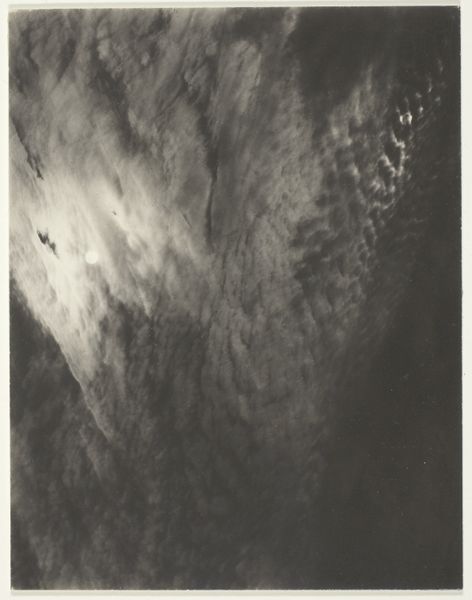

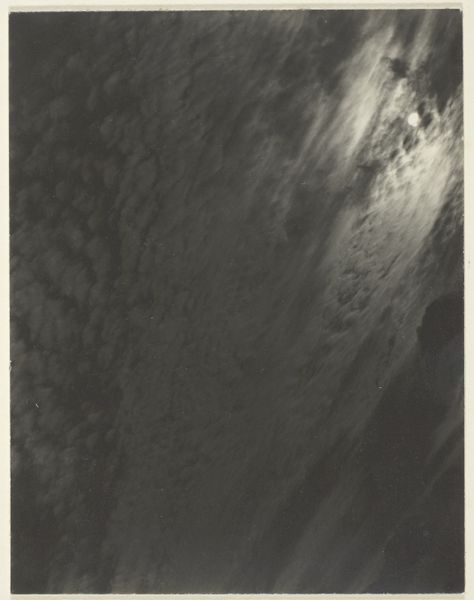

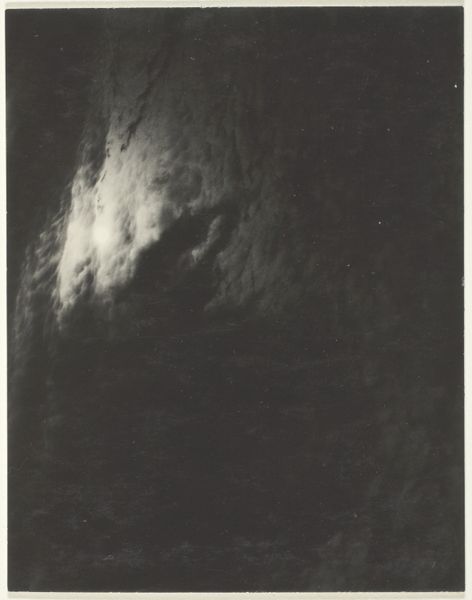

Dimensions: 9.2 × 11.8 cm (image/paper/first mount); 34.9 × 27.6 cm (second mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is Alfred Stieglitz's "Equivalent" from 1930, a silver print on paper, currently residing at the Art Institute of Chicago. At first glance, I see wispy forms, like cloudscapes... It feels very abstract and emotional, despite being a photograph. How would you interpret Stieglitz's choices here? Curator: Well, consider the social context. Stieglitz was working during a period when photography was fighting for recognition as fine art. His "Equivalents" series, particularly these cloud photographs, were revolutionary. They weren’t just about depicting clouds; they were about evoking emotions and internal states. Editor: So, it's more about the feeling the clouds evoke than the clouds themselves? Curator: Exactly. Think about the political climate of the 1930s – economic depression, rising tensions in Europe. Art, including photography, became a means of exploring psychological and emotional landscapes. Stieglitz was trying to demonstrate that a photograph could be as expressive and profound as a painting or sculpture. He chose clouds, perhaps, because they're ephemeral, always changing, and open to interpretation. He wanted the viewer to project their own feelings onto the image. Editor: That makes a lot of sense. It challenges the idea that photography is just a record of reality. It becomes a mirror. So, the museum exhibiting this work also shapes our understanding. Curator: Precisely! The museum provides the context, the validation. Placing it alongside paintings of the same era elevates photography’s status and encourages viewers to consider it on the same level as other fine art forms. Think about how different its reception might have been if it were only displayed in a science museum. Editor: I never considered that. It makes me think differently about how art is perceived and valued. Curator: It's all about the frameworks we build around it. Museums create those frameworks, influencing not only how we see the art, but what we think art *can* be. Editor: Fascinating. I'll definitely be thinking more about the social and political context when I look at art now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.