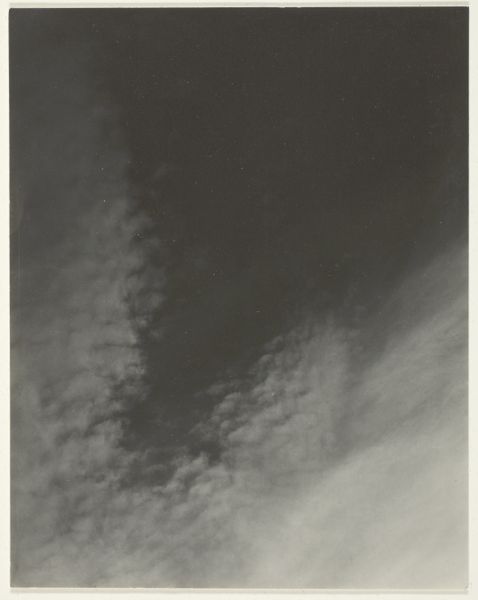

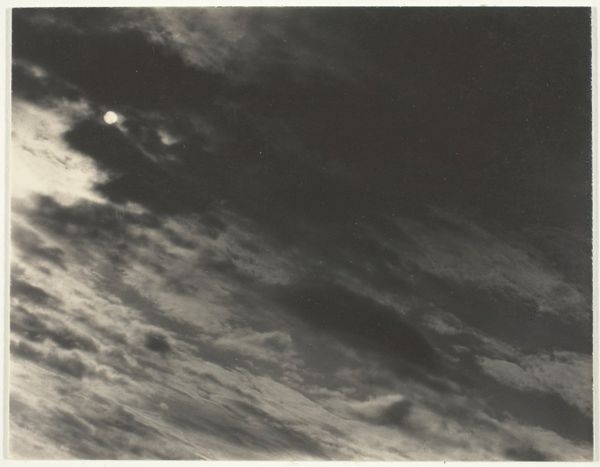

Dimensions: 11.8 × 9.2 cm (image/paper/first mount); 34.3 × 27.6 cm (second mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

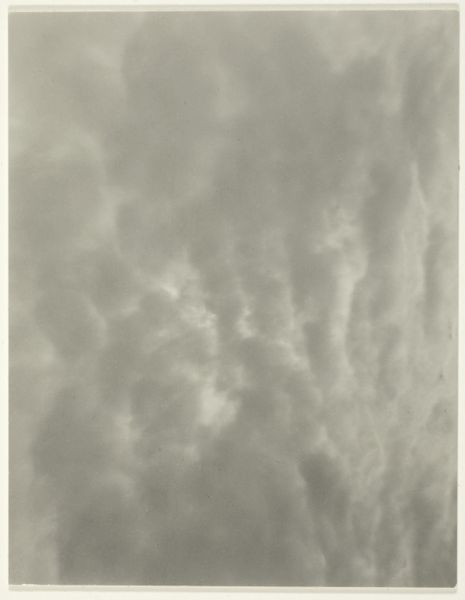

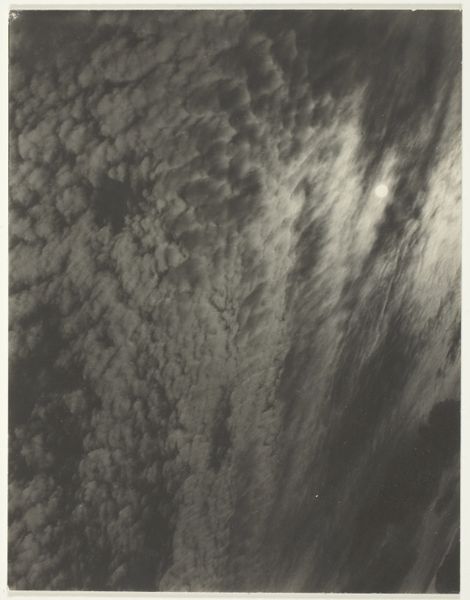

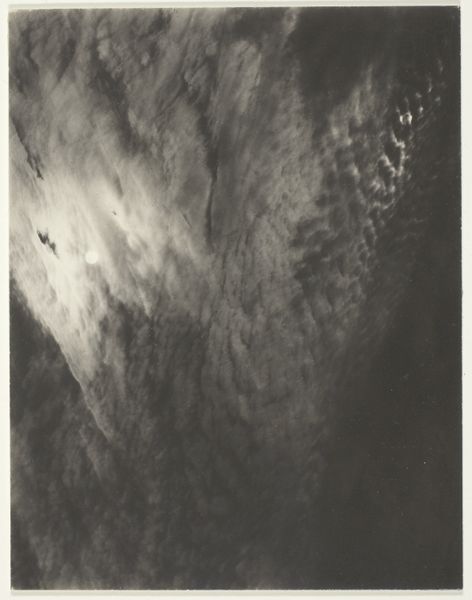

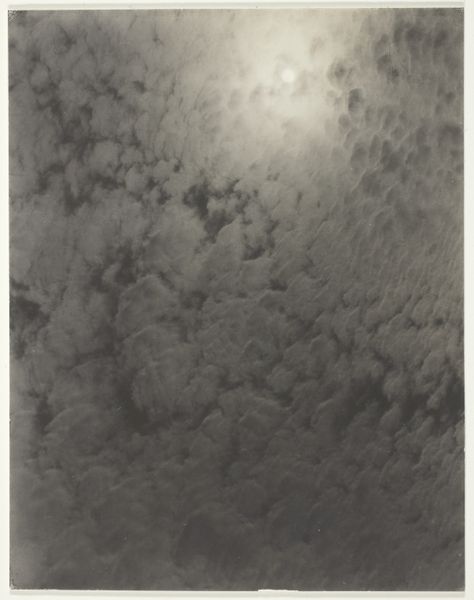

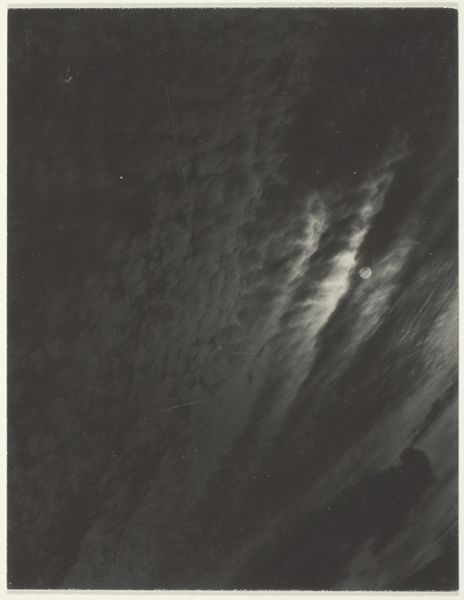

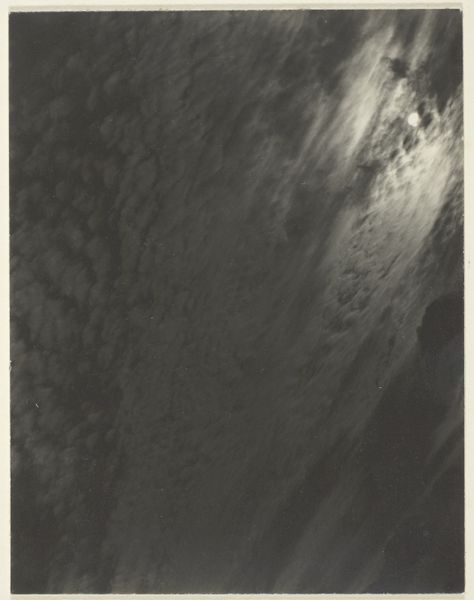

Curator: Here we have Alfred Stieglitz's "Equivalent, from Set E (print 2)", a gelatin silver print from 1923 currently residing at The Art Institute of Chicago. What's your initial take on this? Editor: Stark. Somber. There’s a definite moodiness that pervades the whole piece. It’s an abstract landscape, heavy with implied symbolism in the contrast of light and dark masses. Curator: It is interesting that you call it a landscape since Stieglitz intentionally titled his cloud photographs “Equivalents” to steer away from representational readings. He sought to equate them with internal states, his own feelings made visible. It's part of his broader project advocating photography as fine art in the early 20th century. Editor: Exactly! I see that shift towards internal landscapes mirrored in so many female artists of the period. Was Stieglitz engaging with feminist consciousness as he shot these? What do you think of his politics in framing nature this way? Curator: That's a stimulating proposition. His close relationship with Georgia O'Keeffe complicates any straightforward reading. On the one hand, he championed her work. But at the same time, their dynamic reinforces the patriarchal structures that have historically defined the art world. He promoted the photograph's potential to go beyond literal representation but also exploited O'Keefe’s persona through many portraits, raising ethical questions about representation and consent. Editor: That's the crux of it for me. Whose emotions are we really seeing here? Stieglitz's, projected onto these clouds? Or something more universal, shaped by the very personal contexts from which he came? Perhaps he unconsciously gave more to the observer than he wanted to or that the establishment has been ready to acknowledge. The photo hints at nature being knowable as another like self, but his intent seems self-aggrandizing rather than outward-facing. Curator: It is fascinating how the photograph invites these dialogues even a century later. It remains a powerful, open-ended statement, ripe for critical interpretations. Editor: Definitely, this conversation illuminates not only the photo itself, but also our evolving understanding of the art world, its inherent politics, and our respective locations in relationship to power in our social climate. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.