acrylic-paint

#

acrylic-paint

#

form

#

geometric-abstraction

#

abstraction

#

line

#

suprematism

#

monochrome

Copyright: Public domain

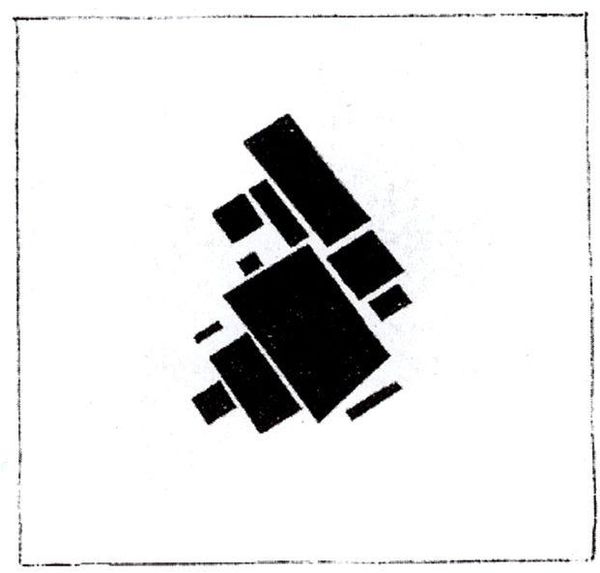

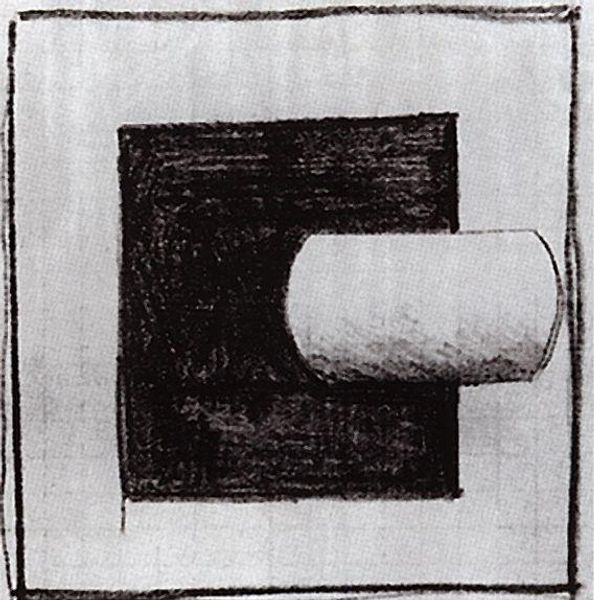

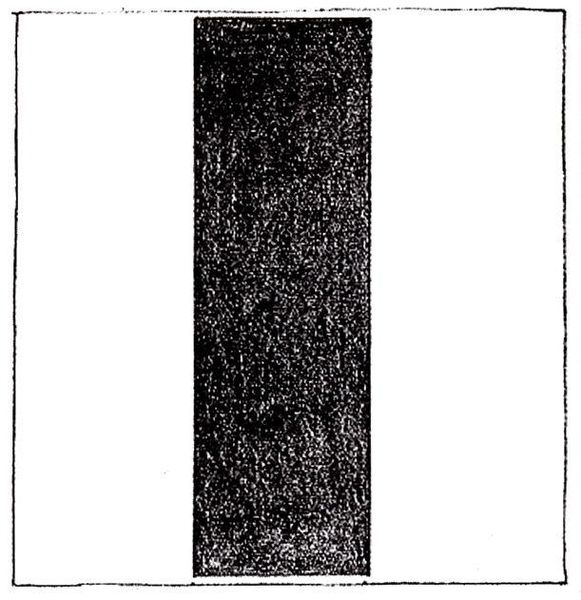

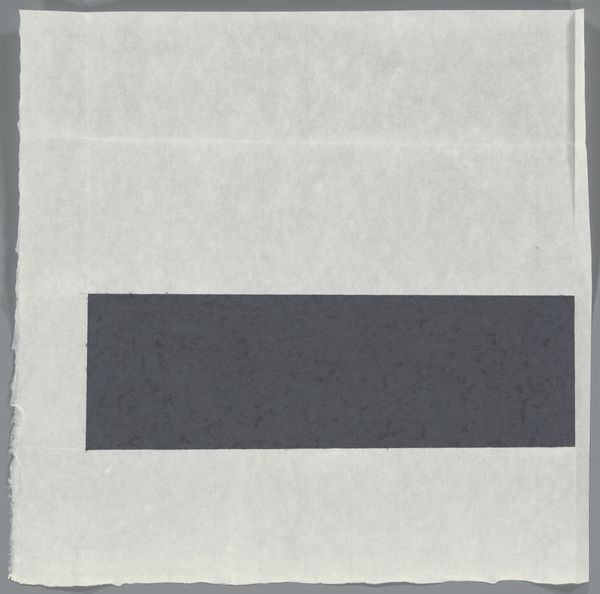

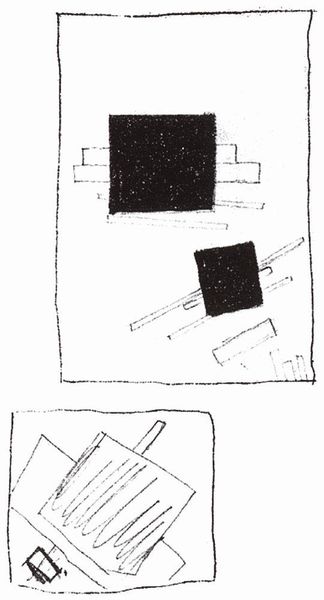

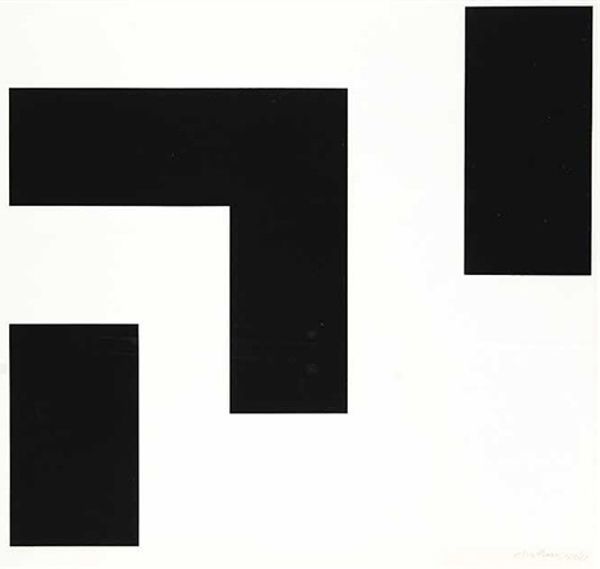

Curator: Here we have Kazimir Malevich's "Movement Suprematist Square," created in 1920. It is, simply put, a black geometric form—two overlapping rectangles—rendered in acrylic paint against a white backdrop. My initial reaction is of visual starkness, even aggressive asymmetry. Editor: Aggressive? Interesting. I see it more as… awkward. There’s a real tension here, between the stark black and white and the unbalanced composition. But tell me, what does “Suprematist” even signify in relation to materiality and production here? Curator: For Malevich, Suprematism meant the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art. He was moving away from representing the external world, seeking a kind of non-objective reality. Looking at how thinly and unevenly the acrylic is applied, one begins to question the possibility of any absolute, "pure" aesthetic. I think there's a potent relationship here between material process and a theoretical manifesto. Editor: That tension resonates deeply when we consider the context in which this was made— the social upheavals following World War I, the Russian Revolution... Suprematism emerged from that yearning for radical change. And Malevich wasn’t just creating art, he was creating manifestos; he imagined these forms transforming all aspects of life, architecture, even clothing. How might this reflect some forms of oppression, as the "form" becomes some type of ideal? Curator: Absolutely. It gets to the core of artistic labor and intention. Consider Malevich teaching, creating a school—he wasn't just interested in the individual gesture, but in codifying a whole system of production, even in what the possibilities of form should do to a proletariat. Editor: Yet the individual painter's touch, evident in the paint application, provides this crucial sense of hand-making, a material contrast to the aspirational totality and machine production being ushered in throughout this historical period. "Movement Suprematist Square" also challenges that by hinting to motion through its arrangement. Curator: Yes, and doesn't the idea of this artwork existing only as pure feeling become quite the opposite, a paradox? A symbol becomes the very antithesis of abstraction itself; a tool used to change politics becomes embedded as an instrument, not a goal. Editor: Right, the "movement" of its title alludes to its dynamism, and maybe reflects how artists navigate ever-shifting grounds to challenge how social change operates and affects lives and art-making. Curator: Well, thinking about how this seemingly simple assemblage embodies and provokes so much complexity about how art gets made, it's tough to look away, despite its austere composition. Editor: Agreed, and framing its history while connecting its form to broader narratives about art and social change allows us to revisit its context more fully, rather than freezing it inside some past ideal or doctrine.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.