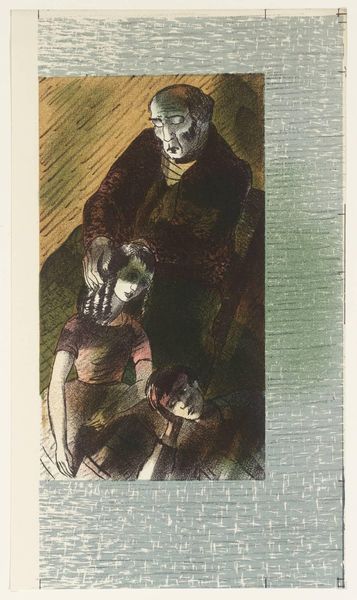

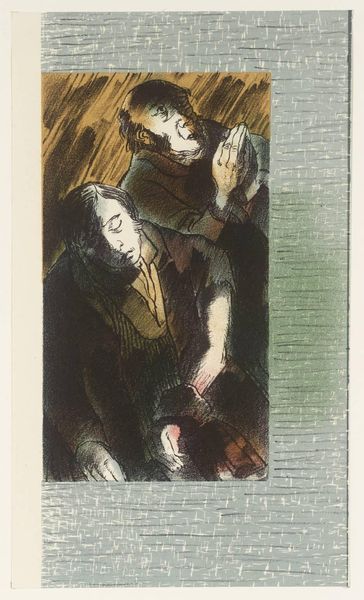

Dimensions: 92 x 73 cm

Copyright: Public domain

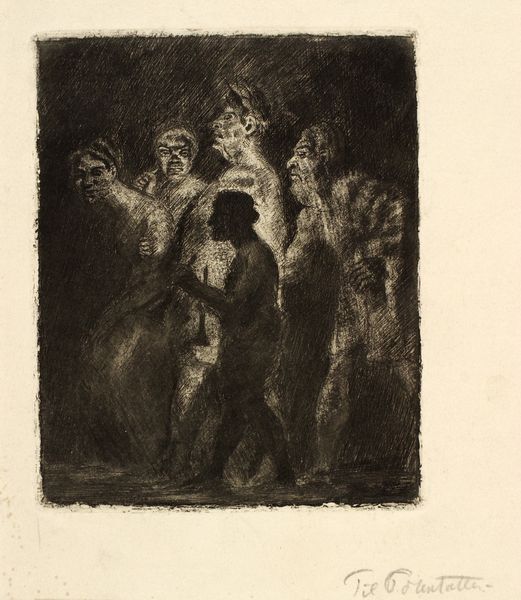

Curator: Here we have Honoré Daumier's "Family on the Barricades, 1848", created in 1854. The lithograph offers a stark view of Parisian life during revolutionary upheaval. Editor: It strikes me immediately as austere. There’s an unsettling quiet intensity to their faces. It seems to ask us something about the collective laboring body in times of crisis. Curator: Daumier was deeply engaged in the political movements of his time. The revolutions of 1848 saw widespread popular uprisings against the established order, calling for greater social and political justice. His art provided the common people a narrative in this complex time of civil unrest. Editor: Exactly. Lithography enabled wider reproduction and dissemination. Look at how Daumier utilizes simple materials and stark lines. It really democratized image-making and its access, in a period that we are dealing with constant changes in labor relations. It’s an extension of the working person’s own ability to create. Curator: Note how he uses light and shadow to create a sense of drama. The older man seems like a beacon. His position may point us to reflect about masculinity, as well as the old man, in his paternal figure. It's not a celebration of violence but a somber reflection on its human cost. What’s even more, Daumier brings forward not the revolutionary heroic figure, but his relatives, a child, his mom, his father. It could suggest a comment about who makes a revolution. Editor: It's as if we’re bearing witness to the materiality of struggle etched in their very faces. It makes us ask, "what do bodies retain of material reality of work?" Daumier wasn't just representing revolution, but engaging in its visual economy through process, a material dissemination and documentation through lithographic process. Curator: In the painting one can see the intersection of class, gender, and age—factors shaping experiences within revolutionary events. The stoic presence of the man, and then there is the quiet fear in the boy's gaze. In that same vein, a feminist perspective could allow us to dive deeper into how these uprisings disrupted existing gendered power dynamics. Editor: And that emotional power is also related to how its mode of creation, the raw feel from the material process. Thinking of his art as product from lithographic stone can provide us insights to the historical conditions that allowed for these voices and representations of working class and revolution to reach many corners of the city. Curator: Yes, Daumier invites reflection on social disparities and our relationship to historical instances and, what’s more, social unrest. Editor: Definitely, his method offers to broaden how one looks at the material conditions in which art and representation come into being.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.