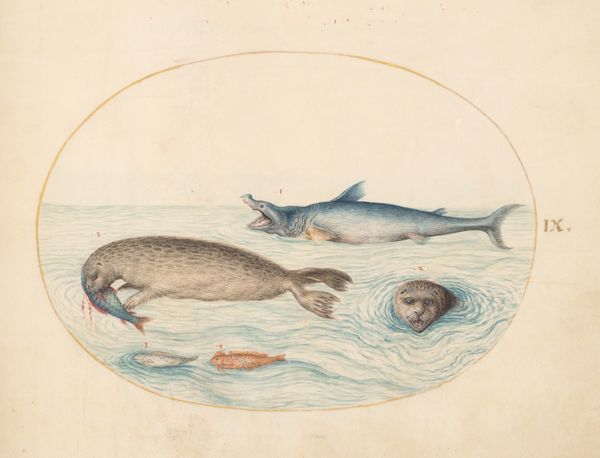

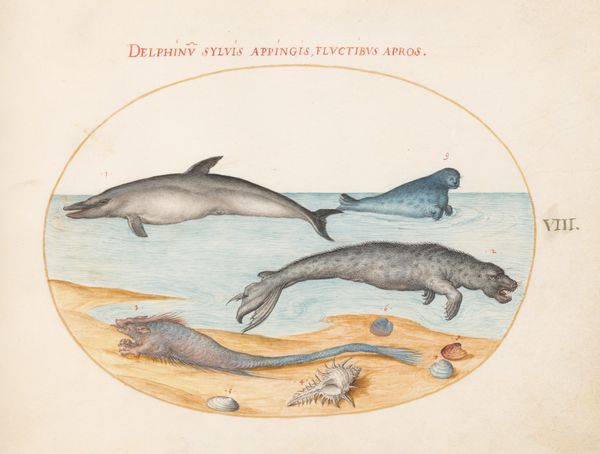

drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

11_renaissance

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

Dimensions: page size (approximate): 14.3 x 18.4 cm (5 5/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: What a curious image, wouldn't you agree? This is "Plate 10: Nine Sharks" by Joris Hoefnagel, dating back to between 1575 and 1580. It's executed with watercolor and drawing. Editor: Definitely peculiar. I am immediately struck by how unreal they seem – these aren't the sleek, almost aerodynamic sharks we’re familiar with from documentaries. They're oddly shaped, almost cartoonish, especially the one that looks like it has sprouted wings! Curator: Well, consider the context. Natural history illustration at this time served a different purpose than it does today. These images were often circulated in books intended for wealthy collectors, emphasizing novelty and wonder, so their aesthetic presentation reflects cultural biases. Editor: Absolutely. So it is worth noting how the production process itself shapes how we understand the natural world. The materiality here, watercolor, suggests delicacy, careful craftsmanship, which would likely enhance the status of both the object itself and its owner. How did that status shape the understanding of nature? Curator: Precisely! Hoefnagel was working in a time of increased global trade and exploration. Sharks, as creatures of the sea, held significant symbolic weight tied to new world exploration and what they brought back from afar. Representations of sharks at this time were enmeshed with this rising colonial enterprise. They often emphasized the strange and fearsome aspects. Editor: And perhaps exoticism drove that production. It begs the question, who was commissioning this sort of art and what power structures were involved in mediating how these creatures were presented? The medium lends a certain degree of credibility, doesn't it? It signifies labor, time, scientific observation—even when, perhaps, the depiction is largely imagined. Curator: I find it so striking how these historical representations, while seemingly quaint today, highlight how much our understanding of the natural world is constructed. Editor: And seeing it presented this way pushes us to see how cultural narratives influence perception. This isn’t just about identifying different shark species; it’s about unveiling the social and political lenses through which they, and, indeed, the world was viewed then. Curator: A world where art served a function not simply about what was shown but about how things were conceived by those in power. It changes the way we engage with such natural history illustrations, I feel. Editor: Agreed. It encourages us to be actively critical, considering the biases embedded in supposedly objective renderings. The materiality informs us beyond surface-level subject recognition and offers ways to ask pressing questions on the cultural stakes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.