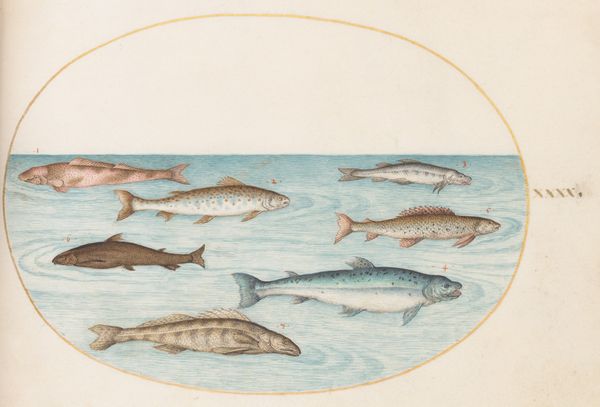

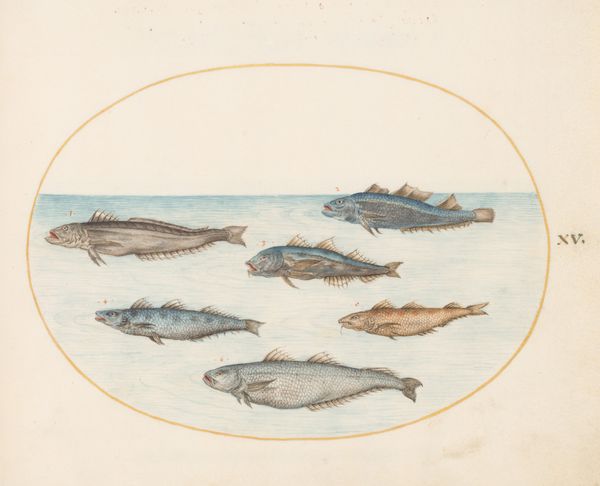

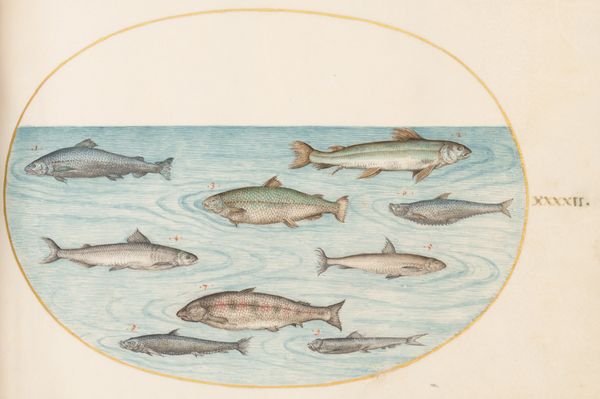

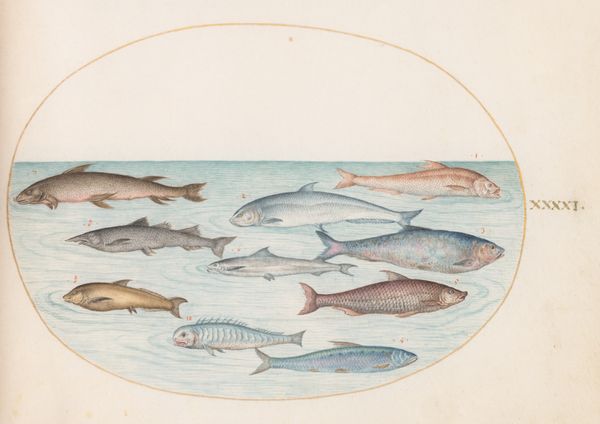

drawing, coloured-pencil

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

animal

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

coloured pencil

#

watercolor

Dimensions: page size (approximate): 14.3 x 18.4 cm (5 5/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

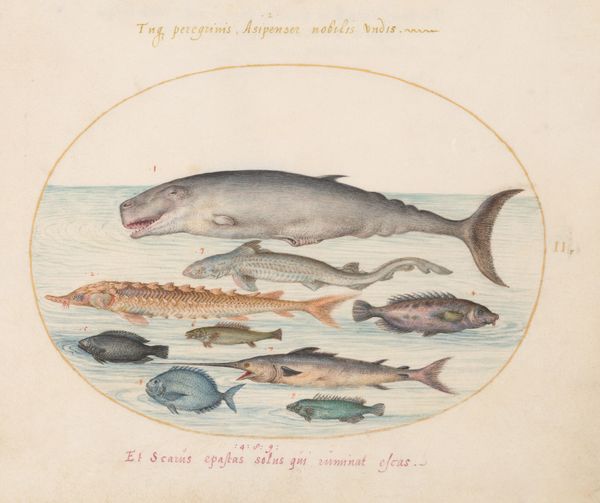

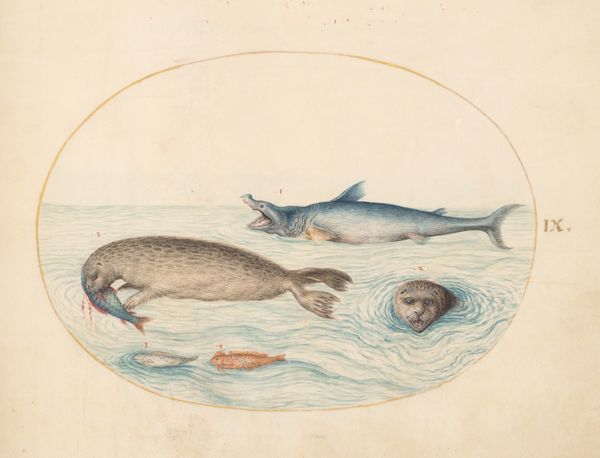

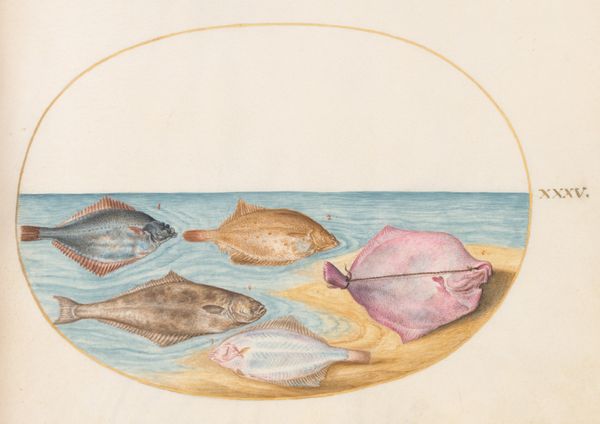

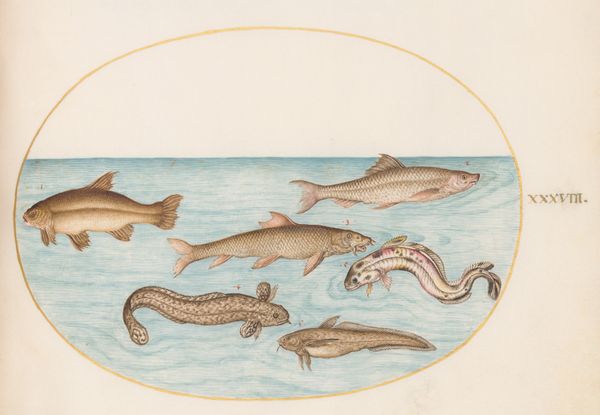

Curator: We're looking at "Plate 12: A Swordfish and Three Other Fish" by Joris Hoefnagel, a drawing rendered in coloured pencil, dating from around 1575 to 1580. Editor: It’s remarkably serene, yet strangely unsettling. They seem suspended, almost like specimens pinned for display, their vacant stares feel almost accusing. Curator: Indeed. Hoefnagel was working during a period of intense scientific exploration. These meticulously rendered aquatic creatures weren’t merely decorative; they reflected a growing impulse to document and classify the natural world. Remember this was also a period of immense colonial expansion and its associated exploitations. How might these seemingly objective renderings relate to Europe’s expanding global reach? Editor: I am immediately struck by the swordfish; it is like a heraldic emblem. Its spear-like bill makes it a clear symbol of power, of conquest of a kind. And these other fish arrayed underneath, become symbols, too— of resources to be had? Curator: It’s crucial to recognise the political and social dimensions, yes. Natural histories such as this one contributed to a visual archive that often supported colonial agendas. The images, in their seeming neutrality, served to legitimise the extraction of natural resources. I think about the emerging global economies during this time. These images may serve as commodity futures of sorts, projecting future yield and profit. Editor: But is there a deeper symbolism here? Think of water itself - traditionally associated with the unconscious, emotions, the unknown. Could these fish, beyond their role as mere specimens, hint at the unexplored depths of human psychology? Is it some hidden fear or unacknowledged truth surfacing? And might their 'accusing' gaze be leveled less at the viewer and more toward self-scrutiny? Curator: That's a provocative thought. If we unpack those connections between visual documentation and power dynamics, can we see how seemingly neutral depictions are intertwined with societal inequalities and the environmental costs of those injustices? How can we grapple with that legacy today? Editor: The dialogue here is fascinating, it brings a deeper and much-needed recognition of meaning than you first appreciate when seeing the drawing. Thank you! Curator: Precisely! Understanding art history requires grappling with both its beauty and its embedded power structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.