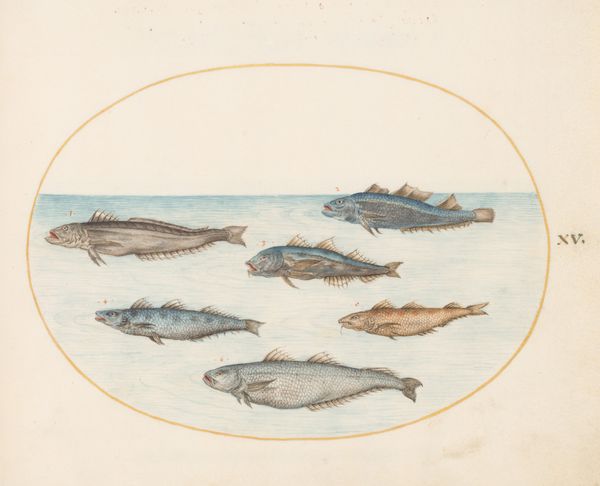

Plate 8: A Dolphin, Two Seals, a Brethmechin, and Shells c. 1575 - 1580

0:00

0:00

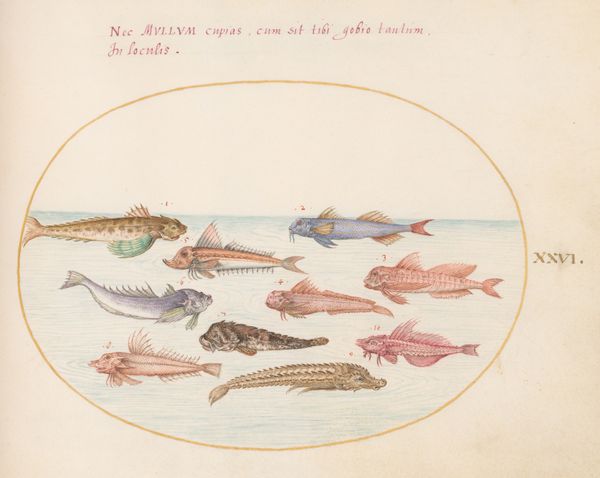

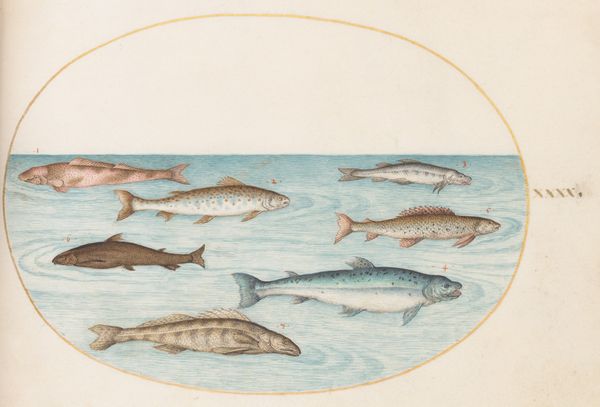

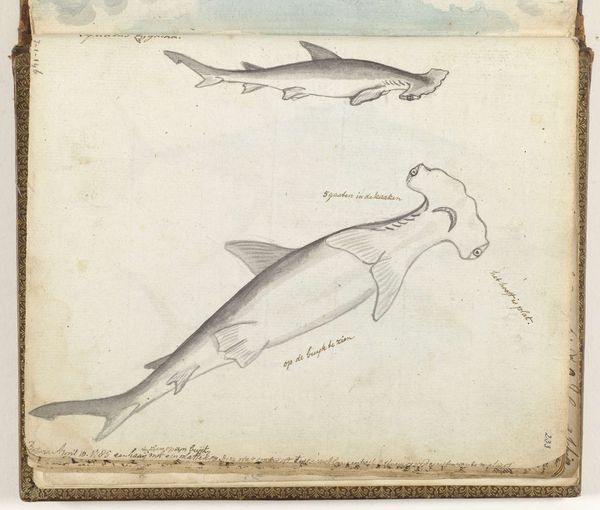

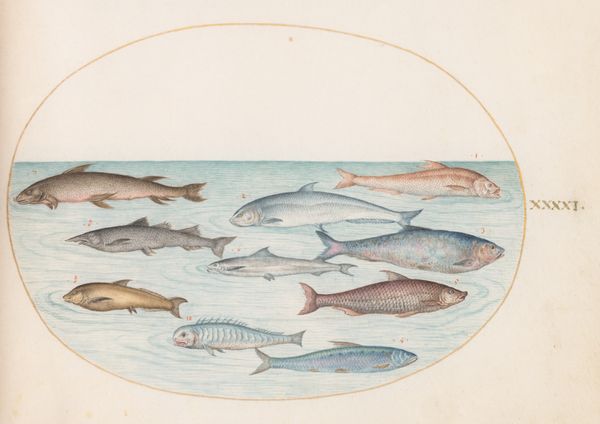

drawing, coloured-pencil, watercolor

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

water colours

#

animal

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

Dimensions: page size (approximate): 14.3 x 18.4 cm (5 5/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

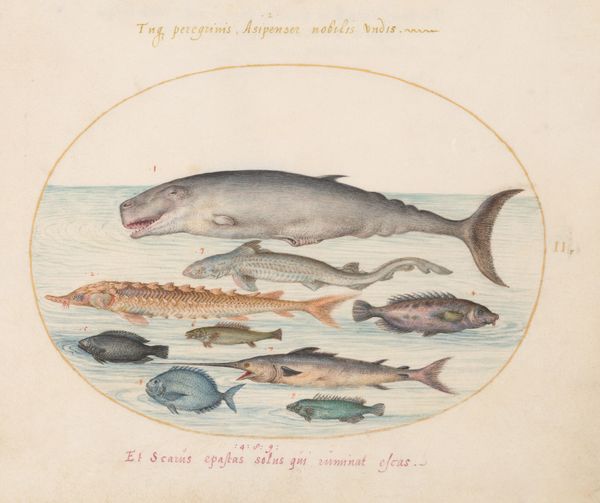

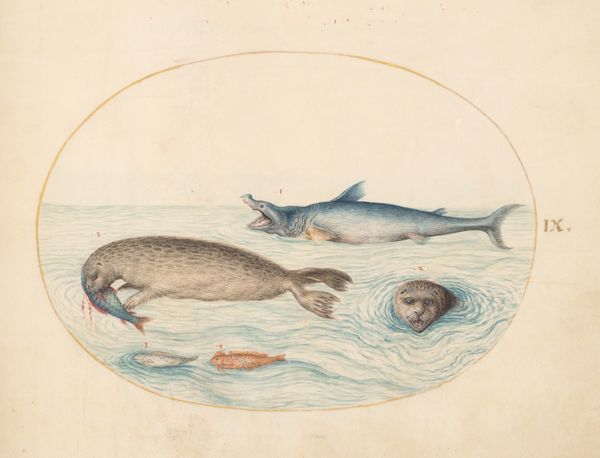

Curator: Today, we are looking at Joris Hoefnagel's "Plate 8: A Dolphin, Two Seals, a Brethmechin, and Shells," created circa 1575-1580. It’s rendered with colored pencil and watercolor. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It's oddly charming. The colours are muted, but the detail given to the different textures, especially the scales on the fantastical brethmechin, is captivating. I'm immediately drawn to its materiality. Curator: Absolutely. And the Brethmechin itself speaks to a cultural moment where the boundaries between the real and imagined were constantly renegotiated. Its inclusion, alongside more naturalistic depictions of a dolphin and seals, points to a society grappling with understanding its place within the natural world, often blending empirical observation with folklore. It raises questions about power dynamics in terms of gender, questioning the social assumptions of Hoefnagel’s era in mapping human perception. Editor: Right. These aren’t straightforward scientific illustrations. There’s a clear emphasis on craftsmanship, on rendering these creatures with painstaking detail, which would require time, specific pigments and considerable skill. Where did these materials originate? How were they sourced and by whom? Who was this ultimately made for? Curator: This kind of art would appeal to wealthy patrons invested in natural philosophy and displaying the bounty of the natural world but it may also be used as a coded means to examine social anxieties about emerging class tensions in cities that are so heavily driven by trade. Editor: Interesting, and look at how the textures vary—smooth for the dolphin, coarse for one seal. The rendering is very evocative. What labor went into mixing those paints? The brushes were likely handmade. This tells us about value too. Curator: It does, indeed. Furthermore, what might the seashells arranged on the bottom edge of the panel tell us about global trade routes? How might this project the colonial intentions? What about those who were denied the ability to express themselves as free humans during that time? Editor: Precisely! The means of representation isn't neutral. And it makes me consider: what resources were allocated to create images like this versus those allocated to alleviate material suffering for others? Curator: It invites such necessary lines of questioning! Overall, looking at this today prompts us to confront the legacy of 16th-century thought, both in terms of its visual techniques, the material process, and what these elements meant, or mean now. Editor: Exactly, this is really such a complex rendering, not just pretty animals, and thinking about art’s production encourages us to re-evaluate so much about our relation to material, to labour, to capital, and really everything surrounding this plate.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.