drawing

#

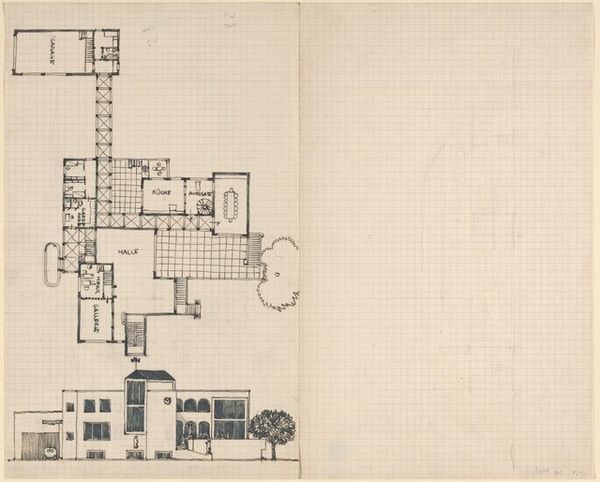

drawing

#

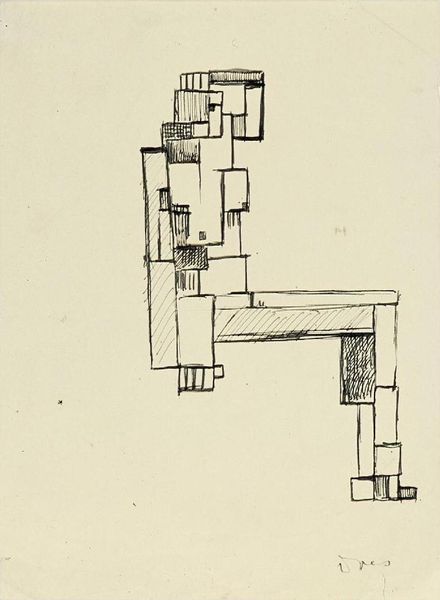

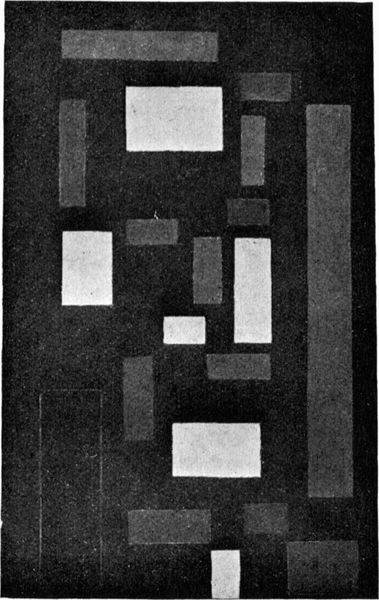

de-stijl

#

dutch-golden-age

#

geometric

#

abstraction

#

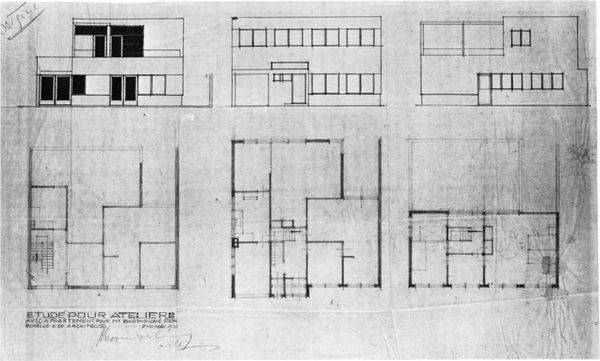

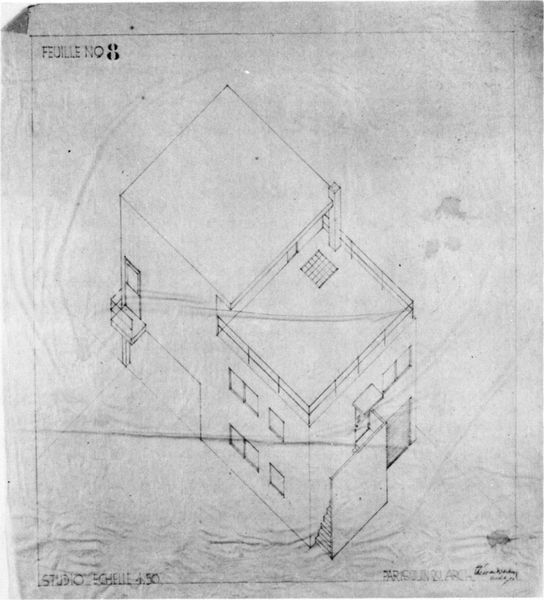

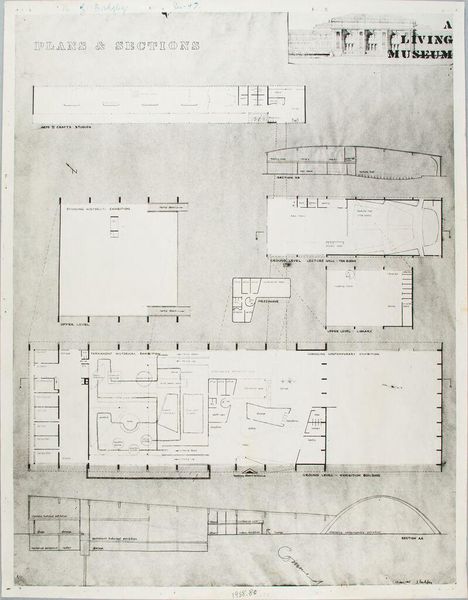

architectural drawing

#

line

#

modernism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: 16 x 10.5 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Here we have Theo van Doesburg's "Study for Rhythm of a Russian Dance," a drawing created in 1918. Editor: Immediately I'm struck by its fragmented yet somehow ordered appearance. It looks almost like an architectural sketch, stark and monochrome. What were van Doesburg's intentions, do you think? Curator: Well, this piece directly relates to the social and political currents of the time. Van Doesburg, like many of his contemporaries, sought to create a universal visual language, one divorced from specific cultural contexts. He felt that geometrical abstraction could transcend barriers. Editor: Ah, that makes sense considering the context. Thinking materially, you see the precise lines against what seems like graph paper – the very fabric speaks to a controlled process, the measured execution. Curator: Precisely! This aligns with De Stijl’s utopian aspirations for social reform, imagining a world remade according to harmonious geometric principles, gender-neutral and politically aligned towards progress. Think about it within the devastation of WWI; art offering hope, perhaps. Editor: So, this almost industrial aesthetic represents a deeper longing? Is the medium then, the pencil and graph paper, a conscious choice? Are those choices an embrace of a modernist utopian vision? Curator: Absolutely. His turn away from explicit figurative representation—what many perceived as the old way of thinking—can be seen as his own attempt to make artworks representative of revolutionary potentiality. How might this relate to modern experiences of alienation, fragmentation and the gendered dimension of it? Editor: You see a yearning towards something different here – I see a tension between control and chaos embodied in materials like a common pencil creating images over rigidly aligned lines of graph paper. Almost like a map. I think understanding his labor illuminates this tension. Curator: Exactly. It becomes more complex when situated with post-structuralist critique and the questions about agency. The drawing pushes and challenges rigid boundaries through geometric forms, what we perceive as fixed can also symbolize resistance against structures and hierarchies in broader social dynamics. Editor: And, of course, each stroke itself is a record of labor – and his intention – transforming something as commonplace as a pencil line into a beacon of artistic, maybe social, transformation. This act itself has an undeniable potency. Curator: So, viewing it now, years later, is important as it provides a point of intersection between art history, theory, politics, and social discourse. Editor: Absolutely. The tension itself underscores a new and deeper appreciation for process and making as acts of transformation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.