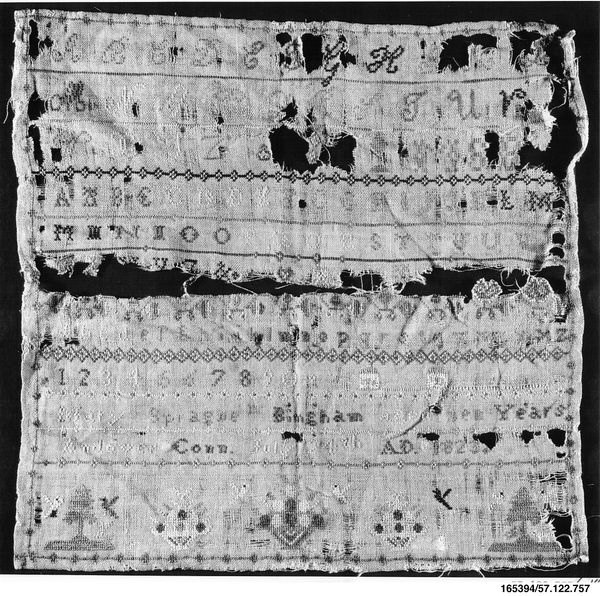

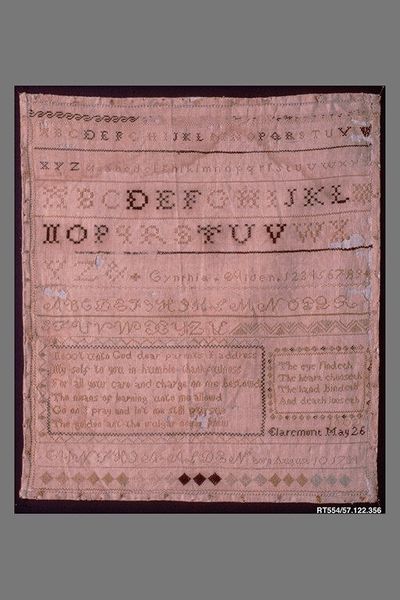

drawing, fibre-art, weaving, textile

#

drawing

#

fibre-art

#

carving

#

weaving

#

textile

#

figuration

#

geometric

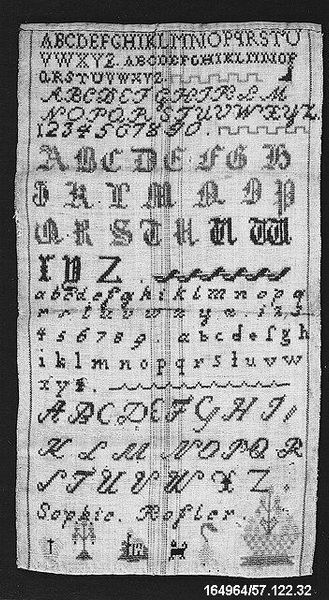

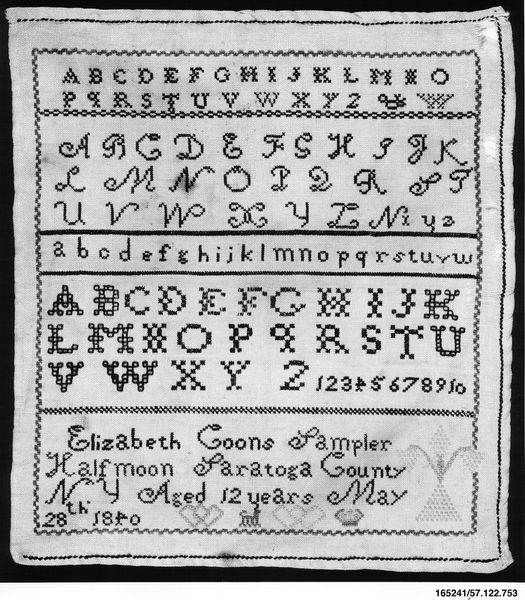

Dimensions: 7 1/2 x 8 3/8 in. (19.1 x 21.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have an embroidered sampler from 1812, made by Mary A. Cheever. It’s comprised of textiles, fibre art, and possibly some drawing. It’s quite simple – a grid filled with alphabets and numbers. What's your interpretation of such an apparently ordinary, domestic object? Curator: "Ordinary" is a deceptive word, isn't it? These samplers, often made by young girls, weren't simply exercises in needlework. They represented a carefully coded entry into a world of social expectations, skill acquisition and moral instruction. We can see them as material testaments to the limited scope of women’s education at the time, and consider how their identities were constructed within very narrow parameters. Look at the regimented lines of letters and numbers, the act of "carving" order on to a fragile material: Doesn't that echo a broader attempt to discipline and contain women’s agency? Editor: That’s a compelling point. I hadn’t considered the limitations imposed by those skills, the hidden social commentary woven, literally, into the fabric. Curator: Precisely! Consider the politics of the domestic sphere, often trivialized and deemed unimportant. Objects like this sampler are the silent witnesses of labour, power, and resistance. How might we re-evaluate this work through a contemporary feminist lens? What are the conversations about identity this piece begins? Editor: So, it’s less about the pretty stitching and more about unpacking the historical and social forces at play? I guess this domestic object isn’t so “ordinary” after all. Curator: Absolutely. It allows us to reflect on how historical constraints, gender roles, and power structures were manifested in everyday practices. Examining what seemingly “simple” works can tell us about power dynamics, shifts our understanding of art and society in a profound way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.