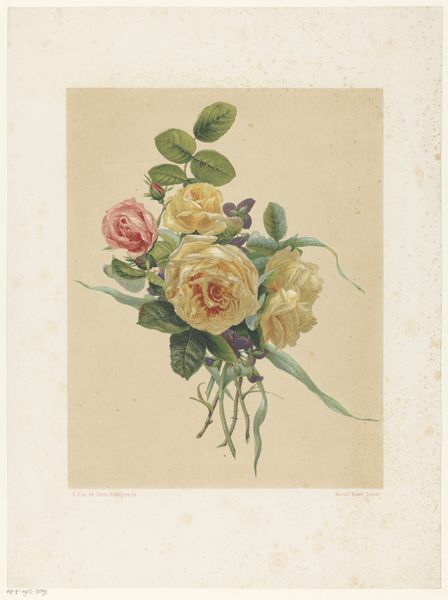

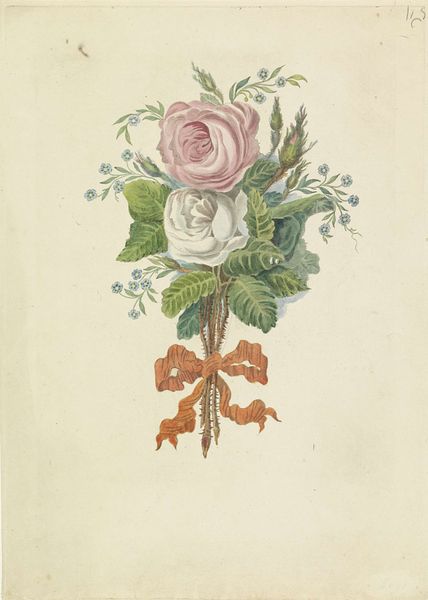

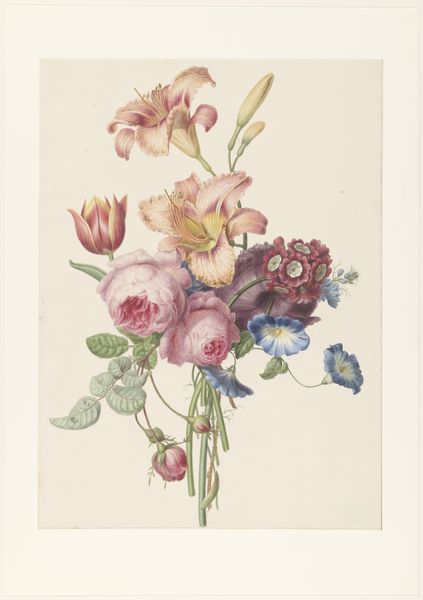

painting, watercolor

#

dutch-golden-age

#

painting

#

watercolor

#

botanical drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 380 mm, width 252 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Before us hangs "Bloemenvaas met onder andere een zonnebloem," or "Flower vase with, among other things, a sunflower," created between 1688 and 1698. It's unsigned and rendered in watercolor. What's your initial reaction to its composition? Editor: It feels... delicate, almost hesitant. The watercolor medium contributes to this lightness, but also the central placement of the floral arrangement against a mostly blank field. There’s an asymmetry, yet the composition remains very stable. Curator: Exactly. The careful layering of washes builds volume within the vase. The artist uses subtle color variations—observe the blues, pinks, and yellows to depict each petal's unique form—to create an impressive illusion of depth on this flat surface. Consider the implications of choosing watercolor over oil for botanical studies during the Dutch Golden Age. Editor: Absolutely, watercolor lends itself to a particular type of scientific observation. Think about the period in which this artwork was conceived. What's presented isn’t simply beauty, but possibly an inventory of resources, too—evoking a deep history of botany as a colonial practice and Dutch interest in mercantilism during the 17th century. What narratives do you see emerging between the delicate handling of materials and their ties to power? Curator: Interesting point. I see a controlled freedom—the structured formality of the urn gives way to a looser, more organic arrangement above. The sunflower, centrally located, acts as an anchor while the surrounding blooms offer gentle tonal harmonies, a common hallmark of the period. I am not sure of making too wide of a stretch connecting botany and Dutch interests in mercantilism when looking at the materiality and design in the frame of early modern still-life traditions in Netherlands and elsewhere, however. Editor: Well, I still find it impossible to overlook that tension in period objects when considering how flowers—often symbols of luxury and wealth—were cultivated within imperialistic projects. It prompts us to engage with art history more broadly, asking who is served or erased by an artist's choices. Curator: Perhaps that interplay between aesthetic observation and a critical re-examination is precisely what makes these works so compelling. It opens possibilities for many interpretations, as we are now doing, after all! Editor: Indeed. By embracing dialogue between aesthetics, material histories, and social contexts, we keep the artwork and its era relevant, continuously posing questions about its meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.