painting, watercolor

#

painting

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

botanical drawing

#

botanical art

#

watercolor

#

realism

Dimensions: height 462 mm, width 338 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

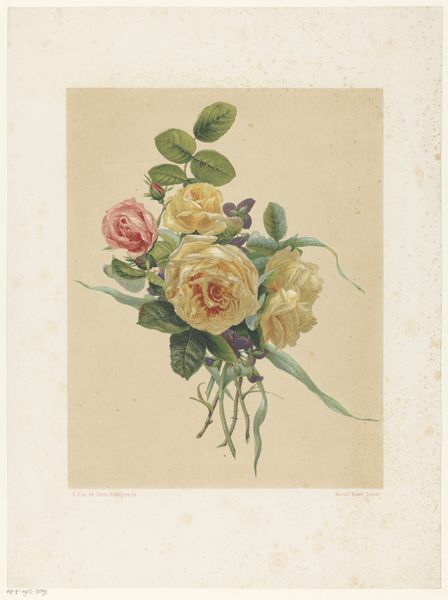

Curator: Henriëtte Geertruida Knip, around 1820, created this piece titled "A Bouquet" using watercolor. Editor: My initial feeling is of restrained elegance. The color palette is muted, but the composition has a lovely, almost accidental grace. Curator: Knip worked during a period of social upheaval in the Netherlands, experiencing French occupation and the establishment of the Kingdom. How might the meticulous rendering of botanicals be interpreted as a subtle form of expression? Did this represent any implicit defiance in a time when explicitly political statements could be dangerous? Editor: The roses at the painting’s center—symbols of love, of course, but also often of secrecy—along with the fleeting beauty of the other flowers feels almost like an elegy. Perhaps she intended them as coded messages of resistance or silent memorials to fallen comrades? Or possibly a longing for the "simpler times" of nature during unrest? Curator: It's worth considering her position as a woman artist during that time. Did the artistic conventions regarding what women "should" paint – flowers, domestic scenes – actually provide a subversive opportunity for her? She could be commenting on feminine passivity. The lilies could, in the context of Christian Iconography, take on specific significances. The bouquet becomes less about surface aesthetics and more about depth. Editor: Precisely! Beyond their apparent fragility, flowers are power. They hold potent meanings, capable of expressing complex emotions and ideas that resonate across time. Looking closely, those blue morning glories often symbolized brevity or unrequited love in the Victorian language of flowers – another layer of potential unspoken meaning here, don't you think? Curator: It reframes our understanding, placing it within an understanding of historical frameworks to consider its role in culture. The act of selecting and arranging these specific flowers transcends mere aesthetics; it signifies something about gender, status, and historical perspective. Editor: Yes, it transforms the painting into something greater than just a still life. It embodies cultural memory, doesn't it? Curator: Exactly. Thanks for the dialogue. It is amazing how one piece of work has so much history. Editor: I agree. It helps when all perspectives can weigh in, including history.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

The taste for overcrowded flower and fruit still lifes became outmoded at the end of the 18th century. Henriëtte Geertruida Knip responded to this change, painting watercolours like this one with only a few kinds of blossoms and, moreover, omitting the vase. Her elegant flower pieces were extremely popular. One of her watercolours even won a silver medal in Paris in 1819.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.