tempera, painting

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

figuration

#

orientalism

#

miniature

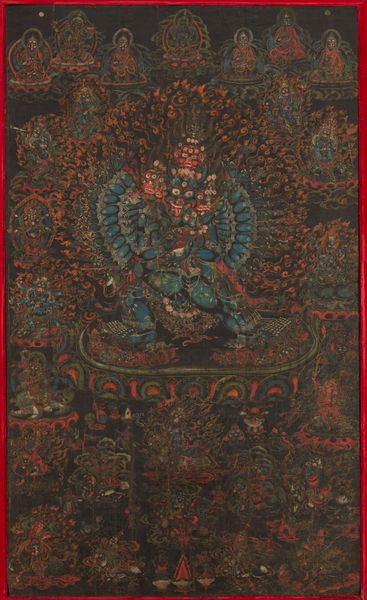

Dimensions: 33 3/8 x 20 7/16 in. (84.77 x 51.91 cm) (image)

Copyright: Public Domain

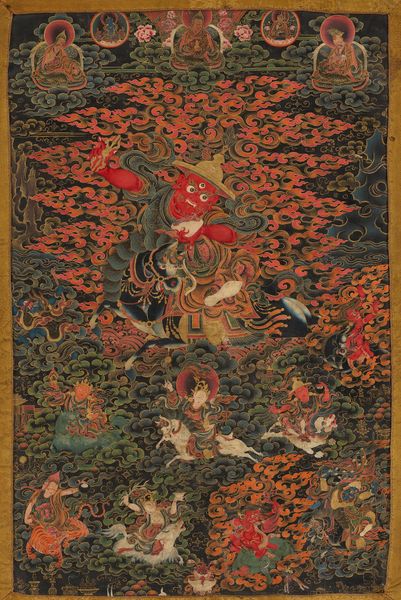

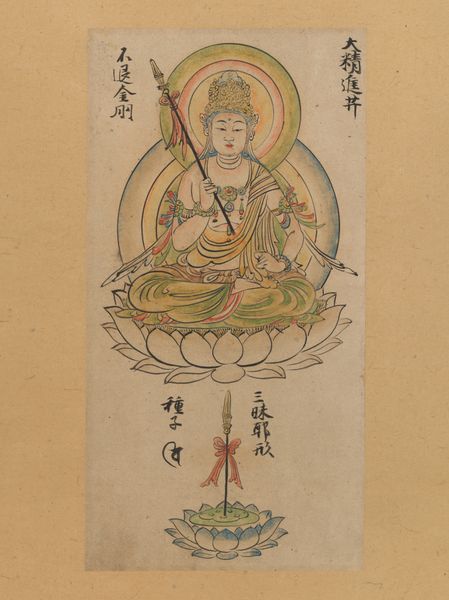

Curator: Woah, chaos. I mean, potent chaos. What grabs me first about this Thangka, this late 19th-century Tibetan painting called "Thangka of Vajrakila and Diptachakra," is its explosive energy. All those arms, faces, wings… it's almost overwhelming. Editor: Overwhelming, yes. And yet, meticulously rendered. I am interested in the surface itself. Look at how finely the tempera is layered, creating a smoothness that belies the complexity of the iconography. The handling of materials points to highly skilled artisan traditions and probably workshops. Curator: Definitely! Each figure is so precisely painted, even in the surrounding mandalas, radiating out from the central deity. I wonder what it felt like to make such a thing—to enter that meditative, detailed state. Do you think there were prescribed color palettes and standard patterns at play? Editor: Almost certainly. This wasn’t freeform expression in the modern sense. There would be codified practices that the artist/artisan had to follow in deploying their medium, which here seems grounded with, say, azurite blue, for these celestial figures. It reflects both available pigments, and a socialized demand for specific symbolic presentation. Curator: So, within the rigid structure, it’s an articulation of devotion? An opening to something beyond ourselves. Editor: Perhaps, but consider, too, the function. These thangkas were used in rituals, teaching aids, devotional objects and portable! Materially embedded within systems of power. And possibly trade... Were the artisans of Tibet sourcing pigments from other empires? Curator: Interesting. I am left thinking about these painted scenes which, to me, convey a sense of controlled ferocity. Is it more about material acquisition, the sourcing of rare minerals? Editor: I see the whole process, including the material resources, artistic labor, and cultural roles of the object. How all those different forms of production were deeply connected in the late 19th century. It gives us an interesting point to assess what this means to our lives in the present day, from the context that produced it.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

In Tibetan Buddhist practice, buddhas and bodhisattvas can express both benevolent and wrathful sides. Vajrakila is a wrathful form of the Cosmic Buddha Vajrasattva, a purifying force who valiantly tramples obstacles on the path to enlightenment. Vajrakila is shown in the center, in union with the female deity Diptachakra, who represents wisdom. The focal meditational deity is surrounded by 10 miniature Vajrakila images, their lower bodies in the form of a triangular ritual dagger to peg down evil forces. Vajrakila’s garments further heighten the graphic vision, with distended eyeballs representing the conquest over human afflictions, such as desire, illusion, and ignorance. Below are guardian deities of the four directions, and above is Padmasambava, a Buddhist monk to whom Vajrakila is said to have appeared in a mystic revelation.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.