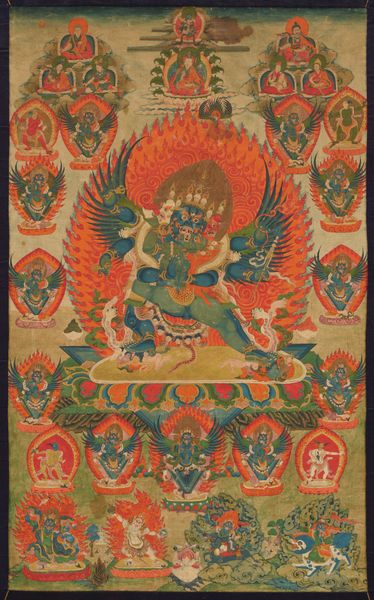

painting, ink

#

portrait

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

ink

#

china

Dimensions: 60 1/2 x 31 15/16 in. (153.67 x 81.12 cm) (image)

Copyright: Public Domain

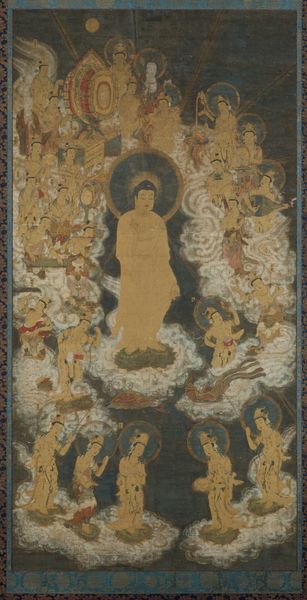

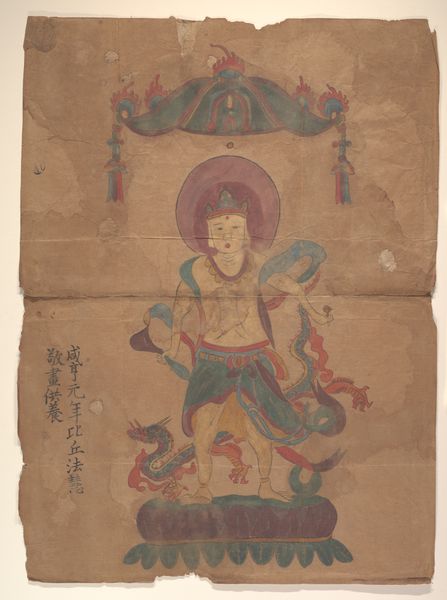

Editor: Here we have Ding Guanpeng's "Two versions of Bodhisattva Guanyin," an ink painting dating back to about 1750. There's an ethereal quality to the rendering of the figures, especially with the heavy use of gold leaf. How do you interpret this work, especially given its cultural and historical context? Curator: What strikes me is the portrayal of Guanyin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, in two distinct forms within a single composition. Ding Guanpeng was a court painter; do you see how this image reflects the syncretism common in Qing Dynasty China, the merging of different belief systems and the negotiation of identity, class and gender within a rigid court structure? Editor: I do see that, especially in the details of their clothing. How does the act of portraying a divine figure relate to the politics of representation? Curator: Consider this painting as a site where religious devotion intersects with imperial power. The act of commissioning and displaying such artwork reinforced the emperor's legitimacy and connection to spiritual authority. Moreover, Guanyin embodies compassion, a crucial virtue in Buddhist teachings. However, within the Qing court, the portrayal of compassion also served to legitimize imperial rule, presenting the emperor as a benevolent ruler concerned with the well-being of his subjects. It is important to investigate the influence of Tibetan Buddhism with strong ties with the Qing court and its artistic and political representation. Editor: That's fascinating; I never considered how carefully these religious portrayals had to be managed in that context. I wonder, could we interpret these 'versions' of Guanyin as speaking to the multiplicity of identity even within the spiritual realm? Curator: Precisely! The multiplicity inherent in Guanyin’s portrayal can be interpreted as reflecting broader societal negotiations around gender, identity, and power during the Qing dynasty, inviting discourse about contemporary representation and its ties with historic visual grammars. What have you found most insightful? Editor: Definitely the connection between religious iconography, courtly life, and political power!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

The court painter Ding Guanpeng was prominent during the Qianlong reign (1736–95) as a painter of Buddhist and Daoist subject matter. In this exquisitely painted hanging scroll, subtle shades of blue and gold combine with fluid drawing and fine details to give the composition a courtly elegance. The scene depicts two versions of Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion, each sumptuously attired in silk and jewelry and holding sutras (Buddhist scriptures) while seated in the position of “royal ease” atop elaborate pedestals. In the foreground are an arhat (one who has attained enlightenment) carrying a walking staff, the child prodigy Sudhana seeking spiritual council, and a six-tusk white elephant, all paying homage to Buddhist thought.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.