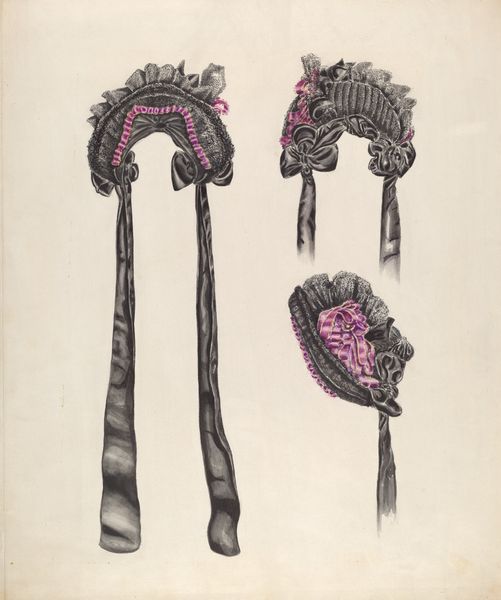

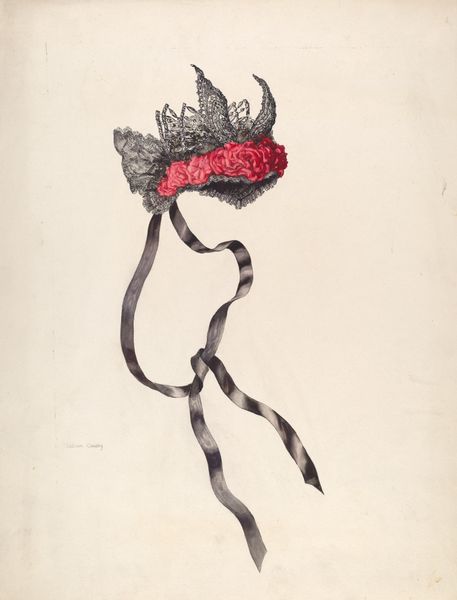

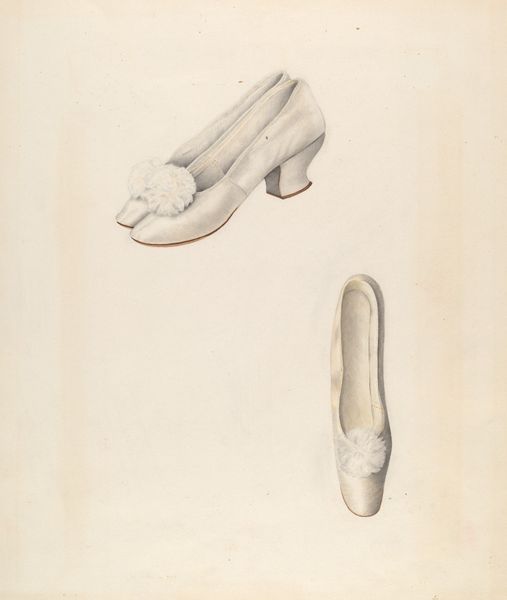

drawing, watercolor, ink

#

drawing

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

watercolour illustration

#

decorative-art

#

realism

Dimensions: overall: 39.8 x 36.7 cm (15 11/16 x 14 7/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Looking at Arelia Arbo's "White Satin Bonnet" from around 1936, the immediate impression is delicate fragility. The multiple perspectives, rendered in ink, watercolor, and drawing, offer an intimate glimpse. Editor: Yes, it's incredibly refined. The materials appear lightweight, suggesting a bygone era when crafting such pieces demanded significant resources and skill. Do you get a sense of labor embedded within it? Curator: Absolutely. Bonnets, like this one, often symbolized respectability and, to some degree, confinement for women. The lace, painstakingly crafted, both adorns and potentially obscures. It invites us to think about social expectations versus individual expression. Editor: Right. It would be very difficult to mass produce these designs at that time, as hand labor dictated how elaborate or complex each could be. And satin represents a real social-economic signifier during that time period, especially contrasted against cottons and other typical working fabrics. Curator: Considering its function, this bonnet whispers about ritualized social performances – who wore it, where, and to what purpose? Perhaps this speaks to aspirations of upward mobility during that time. How would its wearer negotiate restricted movement in these beautiful yet physically restrictive textiles? Editor: Precisely. But thinking about process, do you see an act of rebellion or assertion in the artist selecting such an everyday domestic object and rendering it as fine art? Its inclusion here speaks of valuing women's often-overlooked labor and aesthetic sensibilities. It would be a celebration, perhaps? Curator: I concur! Moreover, the technique itself—ink and watercolor drawing—demonstrates a deep understanding of rendering textures and form. It almost romanticizes an article that may have stood as a gender symbol during its era, as well as signaling privilege. Editor: We have the ability now, looking back at our social constructs then, and see how labor divisions and social roles are now seen in our past in ways they weren't viewed back then. It seems these everyday crafts elevated within our modern sensibilities, as something historical, also becomes highly revolutionary through the benefit of social retrospection. Curator: What a fascinating lens to view this from. Thank you! Editor: My pleasure, it all gives pause and an intriguing angle from which to see art, old and new.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.