#

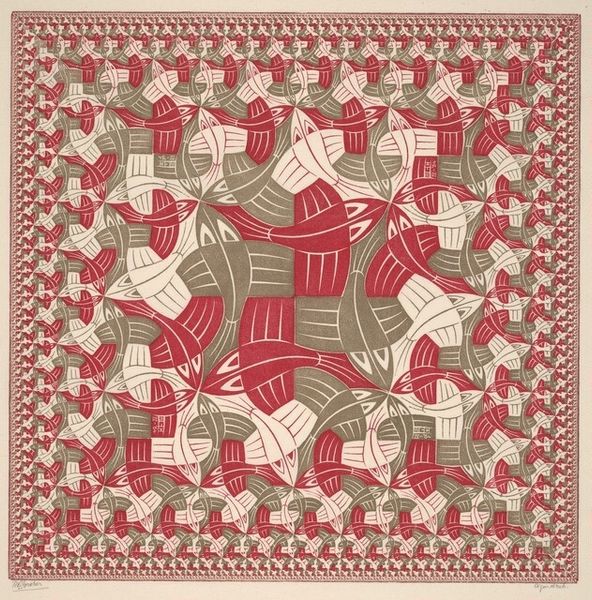

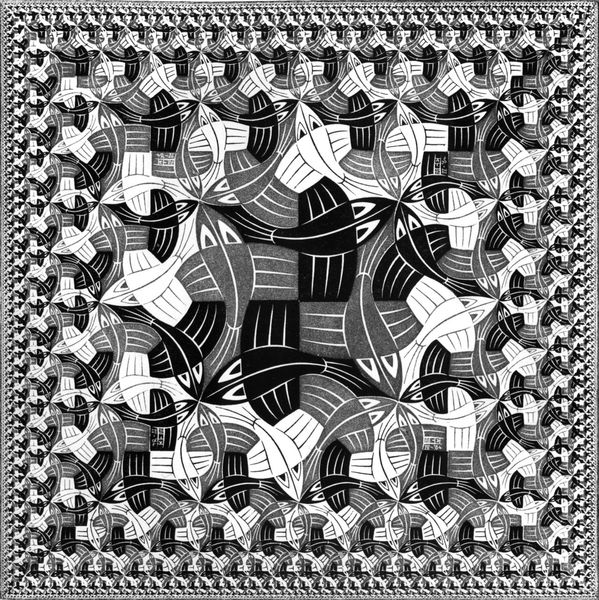

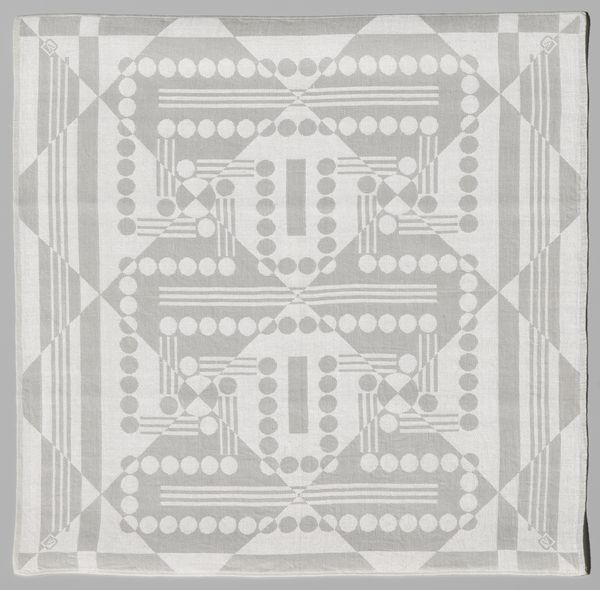

op-art

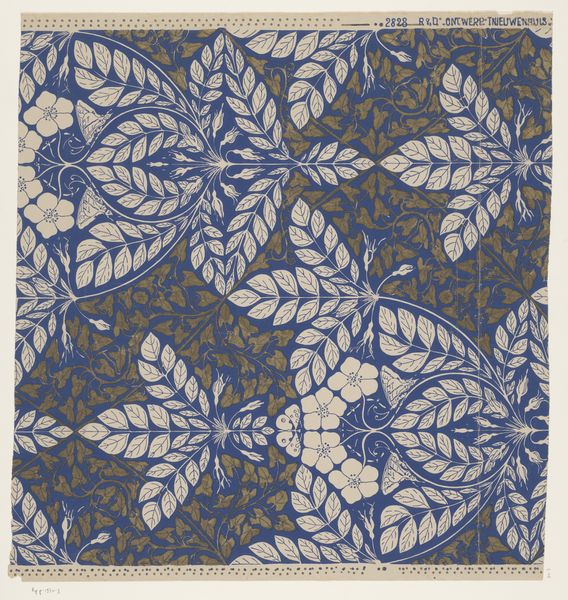

# print

#

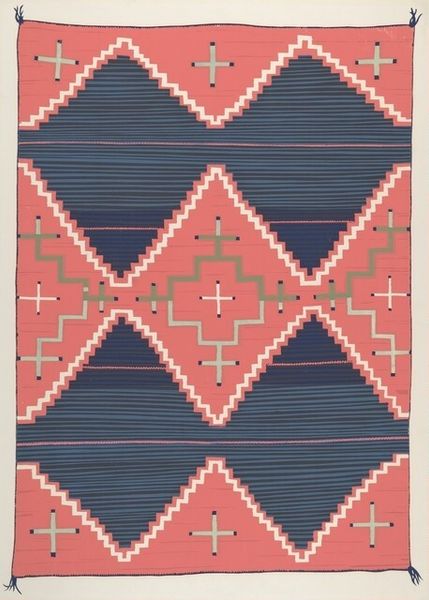

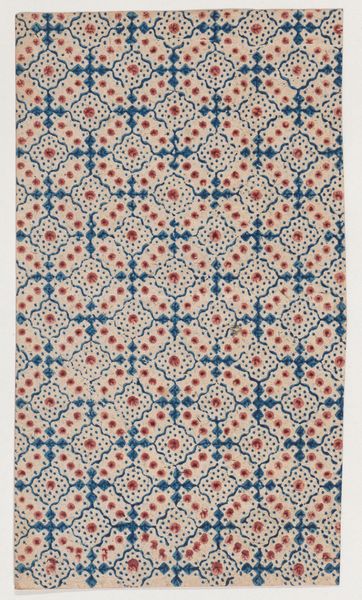

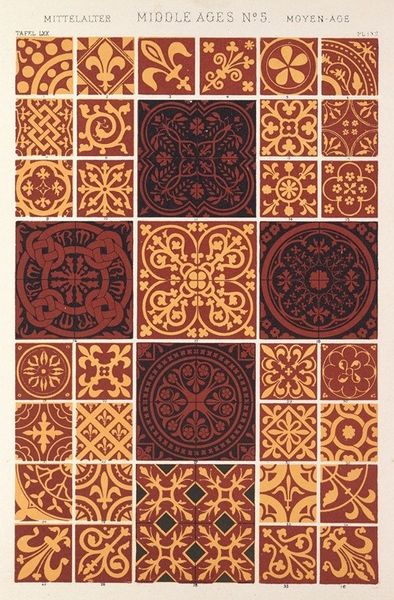

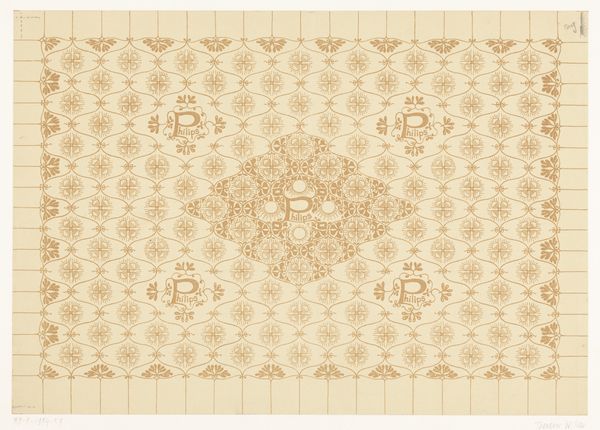

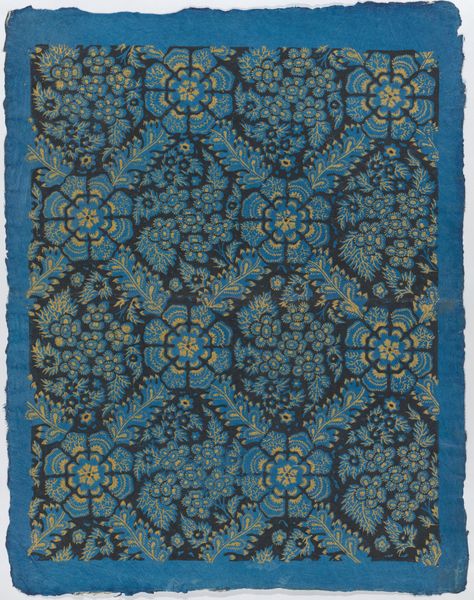

pattern design

#

repetitive shape and pattern

#

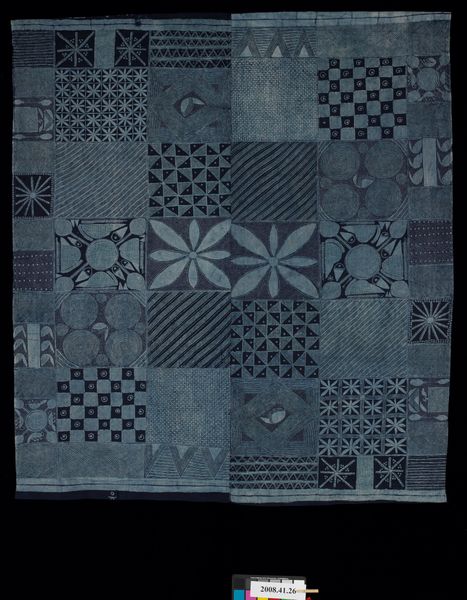

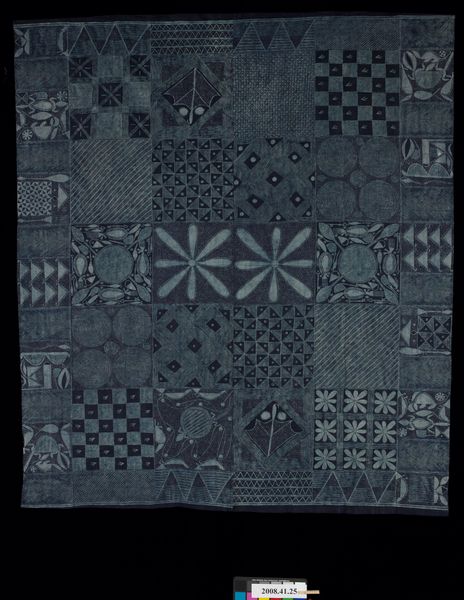

ethnic pattern

#

geometric

#

repetition of pattern

#

vertical pattern

#

abstraction

#

regular pattern

#

pattern repetition

#

layered pattern

#

funky pattern

#

combined pattern

#

modernism

Dimensions: block: 33.7 x 34 cm (13 1/4 x 13 3/8 in.) sheet: 42.9 x 43.5 cm (16 7/8 x 17 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: M.C. Escher’s "Square Limit," a 1964 print, really challenges our perceptions. What do you make of it at first glance? Editor: Visually, it’s captivating yet dizzying. A vortex of repeating figures shrinking into what feels like infinity. There’s a strange comfort in the order and a subtle unease with its implausibility. Curator: Right, Escher was fascinated with tessellations and mathematical concepts, transforming them into these meticulous prints. Considering that tessellations appear across cultures in textile production or bricklaying for example, how do you read this specific take on repeating design elements? Editor: Well, his treatment raises interesting questions. On one level, it’s almost clinical in its precision—recalling the regimentation and rationalization that dominated much of 20th-century thought. Yet, it also reflects this period of geometric abstraction being embraced in mainstream media as modern, or the "new esthetic." It walks this line between critiquing power structures while simultaneously illustrating this visual vocabulary. Curator: Precisely. You see this tension reflected in his choice of materials, the precision needed to create a wood engraving really demonstrates how industrial materials became a new status of modern labor practices that challenged what constitutes high art. The design would’ve been labor-intensive, meticulously planned, and executed. Each line, each repetition demanded a certain conformity. Editor: I can't help but see these interlocking shapes as symbols—fish, maybe, but their ambiguity invites broader interpretations. They mirror our own society’s interconnectedness and the subtle, or sometimes not so subtle, ways we impose structures on ourselves and others, perhaps even unintentionally creating hierarchies and diminishing agency. Curator: Very astute observation about agency within order! Considering the social context of the 1960s, with all its rapid changes and challenging power structures, there’s a layer here that is both subversive and seductive. He’s demonstrating that even in absolute order, illusion and deception can thrive. Editor: It seems Escher isn't merely playing with geometric shapes; he’s reflecting the paradox of modernity itself, which can appear rational on the surface but masks all kinds of societal tensions and contradictions, making his prints of their time and timeless. Curator: Absolutely. This reminds us that engaging with process gives context and opens more perspectives. Editor: Yes, and it shows us that abstraction, like any visual language, always carries its own cultural weight and meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.