print, photography

#

kinetic-art

# print

#

photography

#

geometric

#

academic-art

#

nude

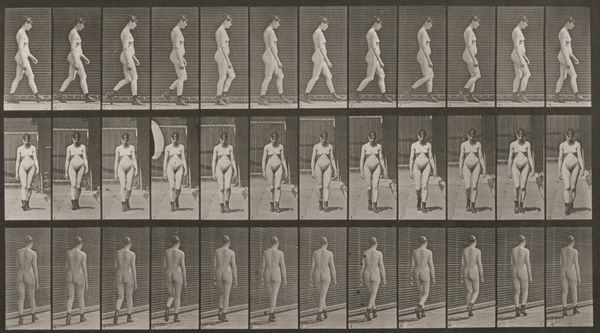

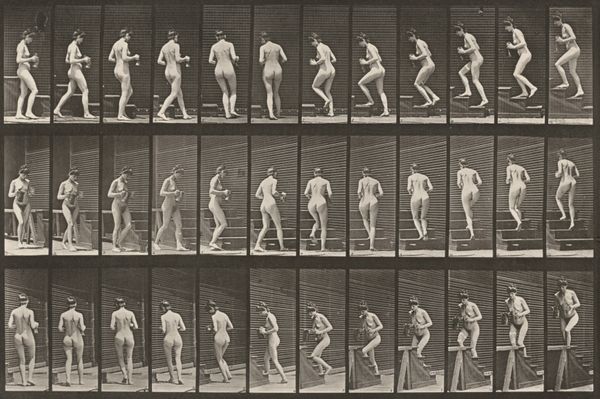

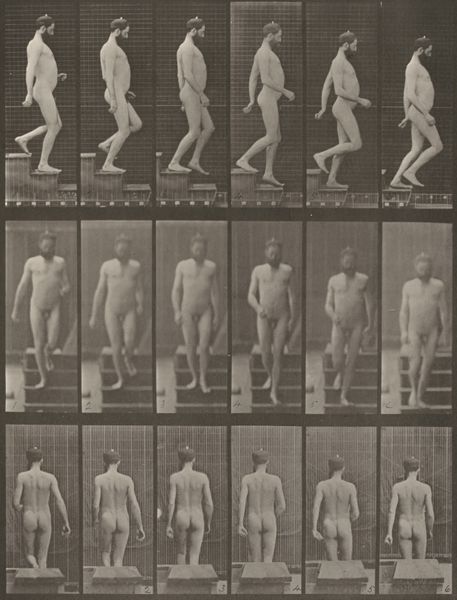

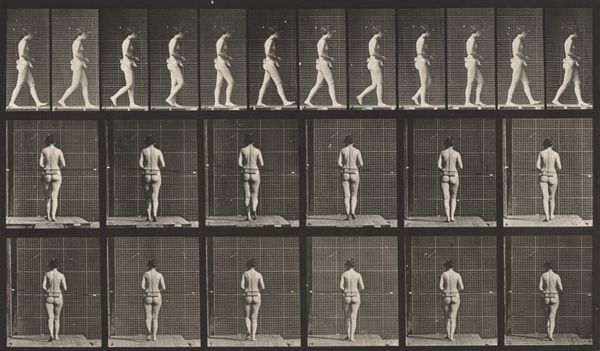

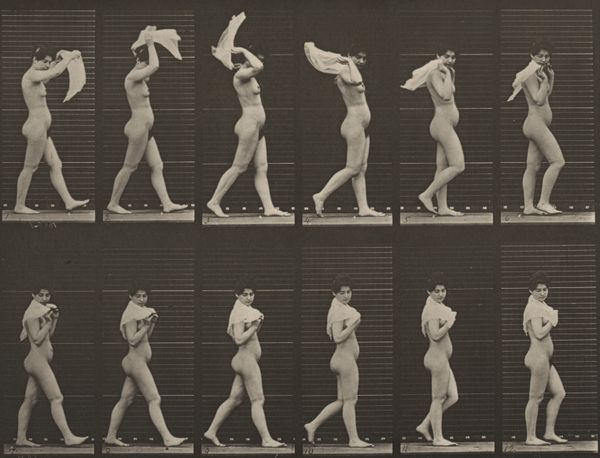

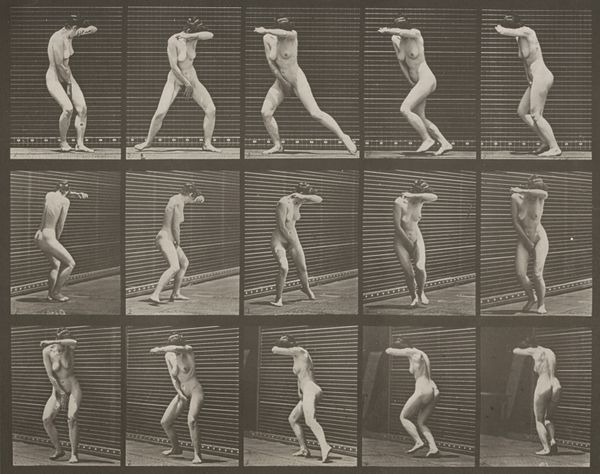

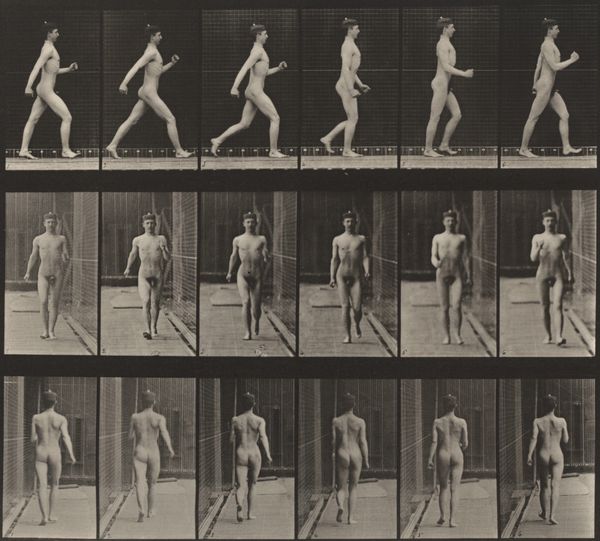

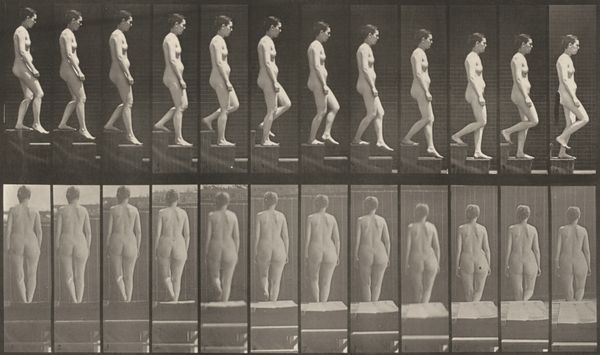

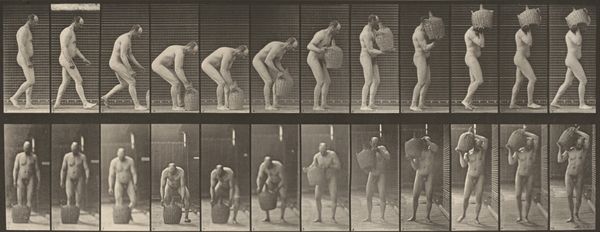

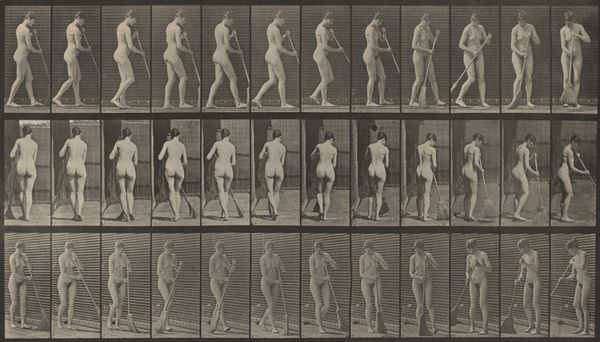

Dimensions: image: 21.8 × 34 cm (8 9/16 × 13 3/8 in.) sheet: 47.6 × 60.2 cm (18 3/4 × 23 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

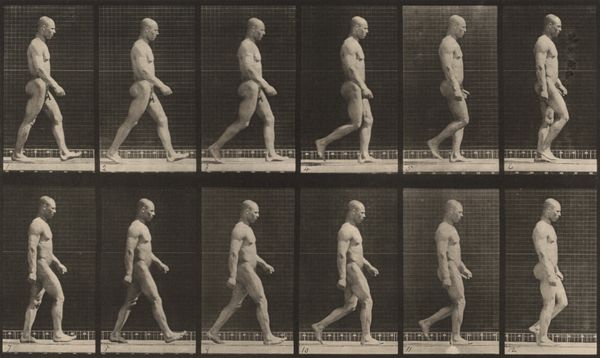

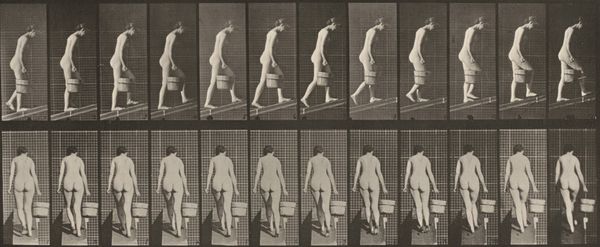

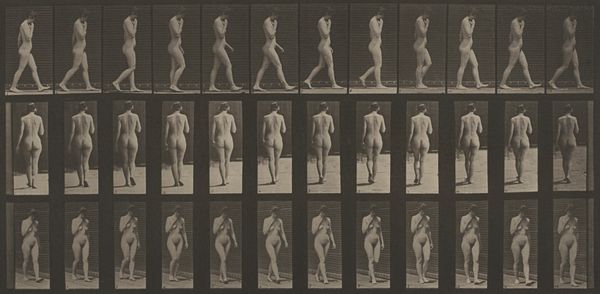

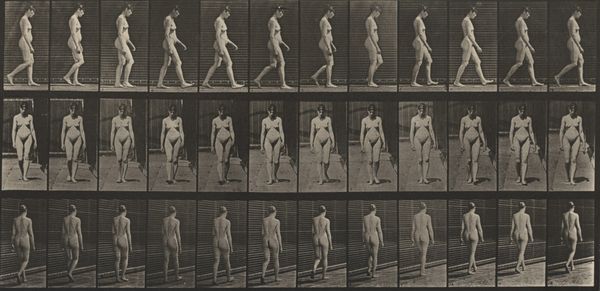

Curator: I find this set of images quite fascinating. This is "Plate Number 126. Descending stairs" by Eadweard Muybridge, created in 1887. It's a photographic print that explores human locomotion. Editor: It's so methodical, almost clinical. The stark grid behind the figure emphasizes this. There’s something both beautiful and a little unsettling about seeing movement dissected like this. Curator: Exactly! Muybridge was deeply interested in the science of motion, influenced by contemporary thinkers in scientific fields and those concerning social theories. He meticulously captured these sequences to analyze how humans and animals move. Think about its impact in fields from art to prosthetics! Editor: Absolutely. You can see the prefiguration of cinema. But it also strikes me – who had access to the 'truth' revealed here? Was this for artists to 'correct' their renderings, for doctors to understand movement pathology, or for the consumption of a wider, curious public, titillated perhaps by the scientific display of the nude body? Curator: Well, initially it was commissioned to settle a bet about whether all four hooves of a horse left the ground at the same time during a gallop! Then it expanded into something more ambitious. It points to a fascinating tension between scientific inquiry, art, and the objectification inherent in image-making itself, doesn’t it? Editor: Indeed. The figure here isn't just a body in motion; it’s also subject to the gaze, both scientific and potentially exploitative, recalling long histories of scientific racism which attempted to codify physical attributes. We need to reckon with that as we engage with images such as these. Curator: That’s a very important point. Situating it within the context of the late 19th century really underscores these issues – a time when ideas about race and gender were being rigorously 'scientifically' investigated, often to uphold existing power structures. Editor: Thinking critically about why and how we look becomes all the more imperative with historical material like this. What questions are we bringing to the image, and how do those intersect with its own historical biases? Curator: This is what makes an apparently simple photograph such a potent object of study, isn’t it? It's not just about freezing motion; it's about interrogating the act of seeing itself, as well as how scientific knowledge is generated and used within specific cultural and power structures. Editor: Precisely, an archive of objectification made visible. The legacies of such acts continue to influence power structures today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.