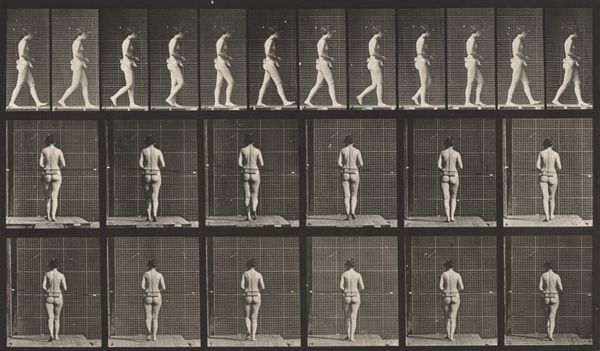

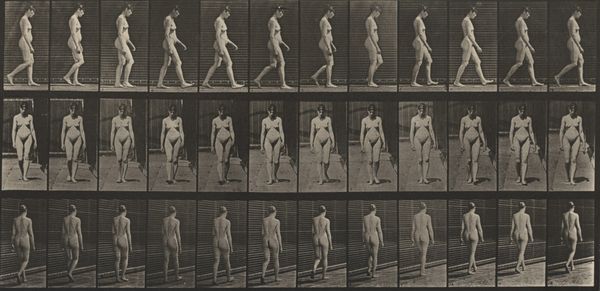

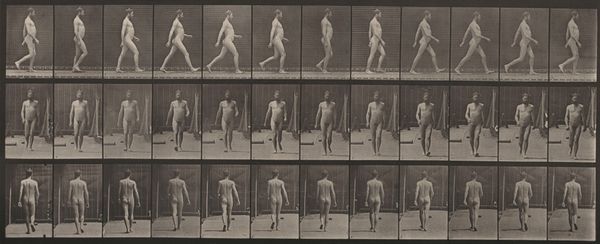

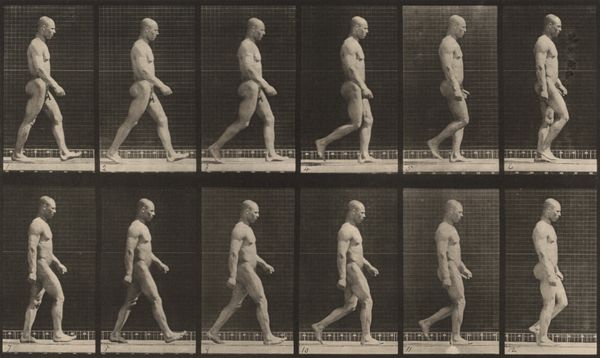

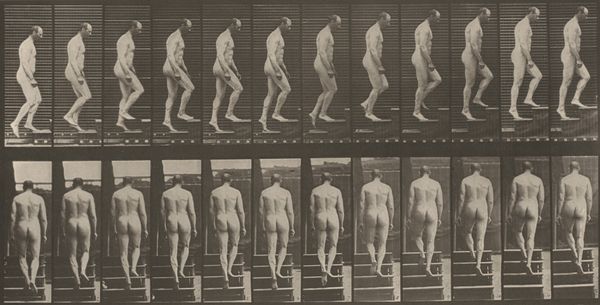

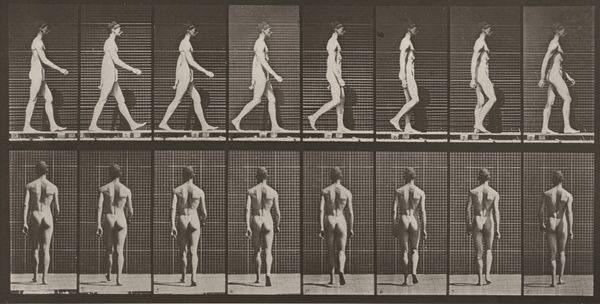

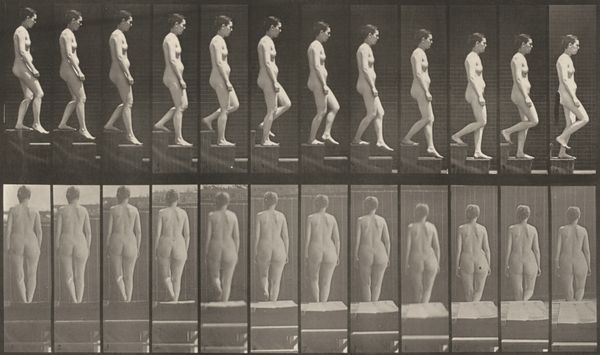

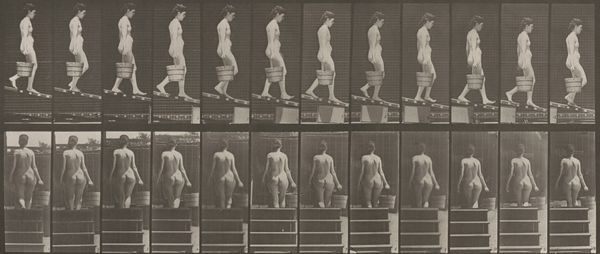

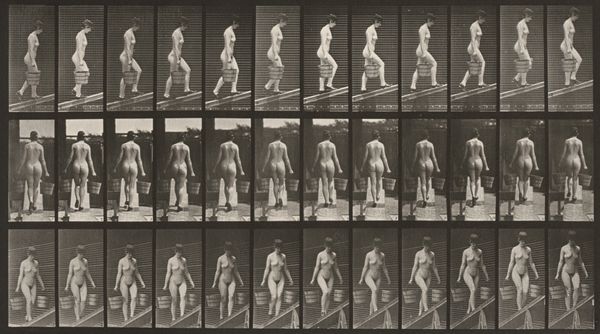

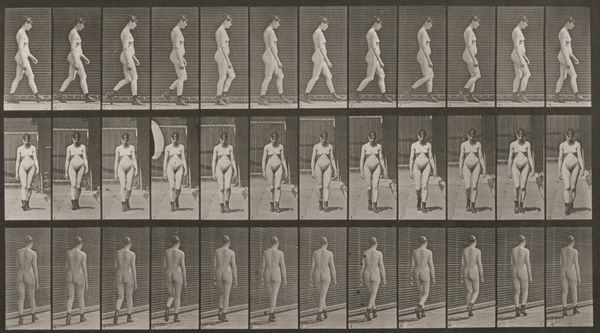

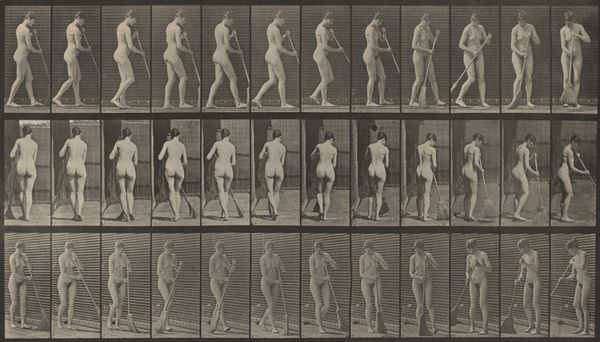

Plate Number 84. Ascending an incline with a bucket of water in right hand 1887

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

realism

Dimensions: image: 17.3 × 41.5 cm (6 13/16 × 16 5/16 in.) sheet: 47.85 × 60.4 cm (18 13/16 × 23 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

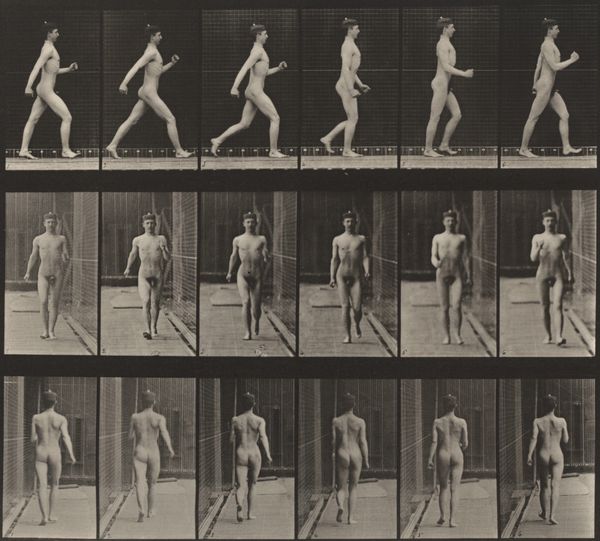

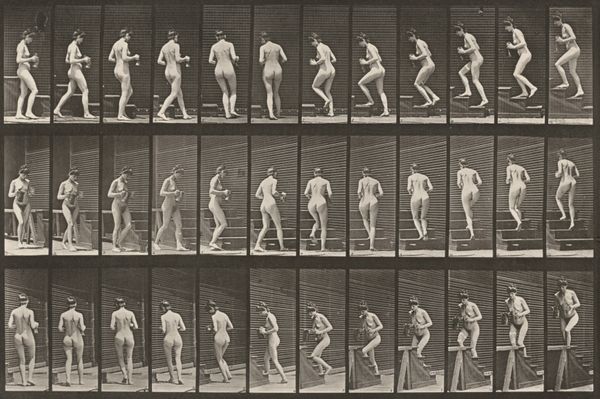

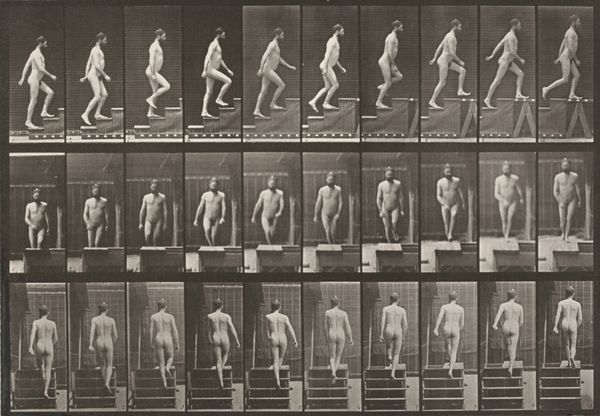

Curator: Here we have Eadweard Muybridge’s "Plate Number 84. Ascending an incline with a bucket of water in right hand," a gelatin silver print from 1887. The series presents a figure in motion, segmented across a grid. My first impression is how systematically Muybridge captured the individual stages, making the image look almost clinical. Editor: It strikes me, too, how this is ostensibly about science, movement, but carries strong undertones of the Victorian obsession with controlling the female body. The female nude subjected to rigorous observation and categorization feels distinctly… surveilled. Curator: Exactly. Muybridge employed a battery of cameras triggered sequentially to freeze these moments. The resulting images provided valuable data for scientific study, and were groundbreaking for motion picture development, of course, but looking through a material lens we have to consider that Muybridge pioneered his methods using both animal and human subjects from varied class and ethnic backgrounds in the Philadelphia and San Francisco areas, with labor and objectification very close to one another here. Editor: Right, we can’t ignore that the power dynamic inherent in the male gaze here. She is reduced to a set of data points in a very limited story arc in service of scientific and artistic "progress." Her agency, her own narrative, is entirely absent from this. What labor was involved and for whose progress? Curator: Think, too, about the labor involved in preparing each print, handling the chemicals, and precisely aligning each image to construct that final grid and what it says about late 19th-century technology and reproducibility. The grid organizes time and action as quantifiable units of labor itself. Editor: I find myself wondering about the sitter’s life beyond these frames. What were her motivations, what were her days like? The lack of contextual information feels like an erasure, reinforcing the detached, objectified reading of this work and speaks to the art-historical treatment of similar women since antiquity. Curator: It is precisely that tension, between objective study and the subjective lived experience, that makes this image so compelling still. And that labor invested from both sides—camera to subject. Editor: Ultimately, looking at the social conditions under which these types of works were developed highlights how identity is constructed and perceived, but also about the ethics of representation then and now, pushing for more nuanced dialogues that go far beyond pure anatomical observation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.