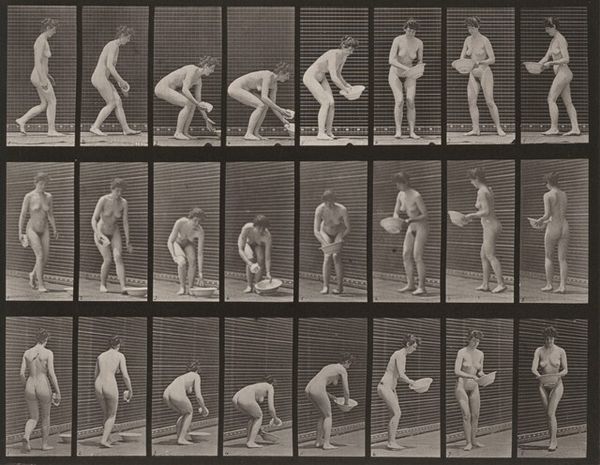

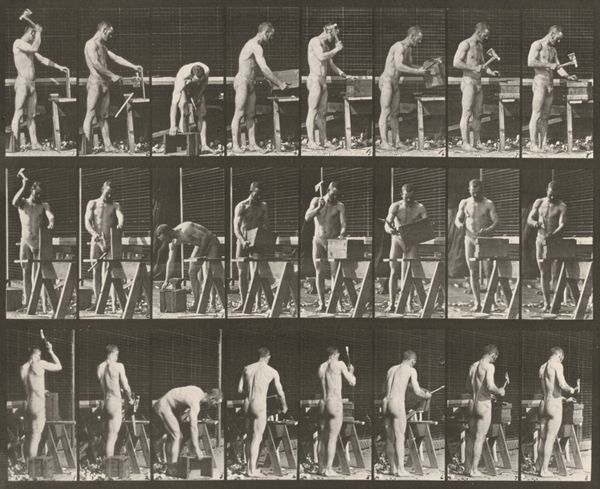

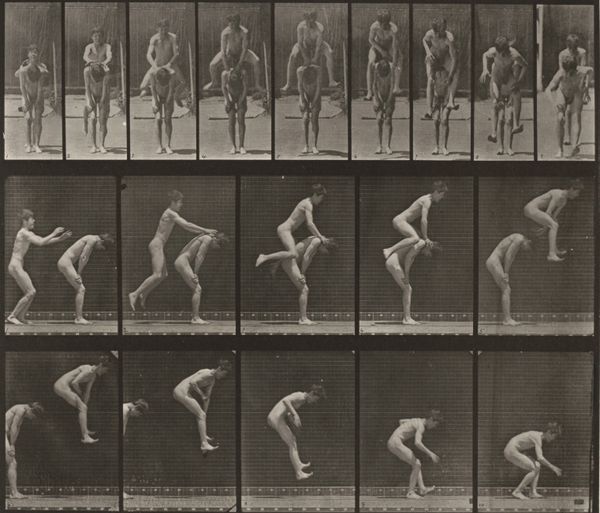

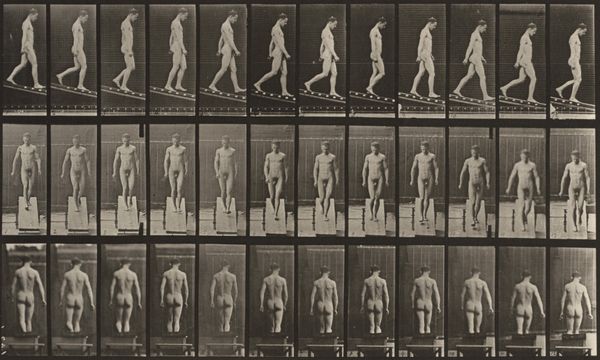

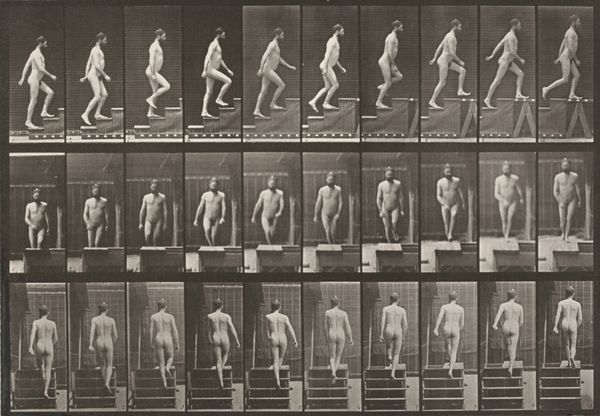

Plate Number 218. Stooping and lifting a full demijohn to shoulder 1887

0:00

0:00

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

film photography

#

pictorialism

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

film

#

nude

#

brown colour palette

Dimensions: image: 17.1 × 43.8 cm (6 3/4 × 17 1/4 in.) sheet: 47.6 × 60.3 cm (18 3/4 × 23 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

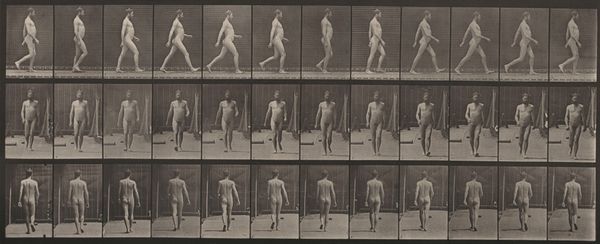

Curator: Here we have Eadweard Muybridge's "Plate Number 218. Stooping and lifting a full demijohn to shoulder," a gelatin-silver print from 1887. What’s your initial read? Editor: It’s evocative of early scientific observation. Stark and analytical, yet the fragmented movement creates an odd sort of visual poetry. Curator: Precisely. Muybridge uses the grid to dissect human motion. Notice the composition: Two rows, each containing a sequence of images capturing incremental changes in the subject's posture. The light, uniform throughout, renders form with clarity, devoid of expressive shadows. Editor: The absence of setting intensifies focus on the body itself. It almost dehumanizes the subject, reducing him to a set of coordinates. Is he a volunteer or paid subject? His socio-economic context remains unseen, lost amidst the grid's demand for clinical detachment. One also wonders about the implied labour. Curator: The formal qualities support your observation. The repetition of the body emphasizes mechanical movement. Each frame documents a precise phase—the stooping, lifting, the shifting weight. Editor: This reduction speaks to broader societal structures. Muybridge’s work emerged during a period when scientific rationalism sought to dissect and categorize everything, including the human body, potentially aligning with theories concerning labour, efficiency, and even control. How are these movements perceived? Dignified or demeaning? Curator: An astute observation. While the study ostensibly serves scientific goals, the aesthetic decisions — the stark presentation and isolation of the figure — are critical to understanding its overall effect. Stripped down as a mere component. Editor: It makes me question how technological advancement shaped perception of the body during that time. How did these fragmented portrayals influence notions of personhood, labor, and physicality at the beginning of this scientific age? It certainly prompts reflections on vulnerability and control. Curator: Indeed, we’ve observed the intersections of form, intention, and historical context to better see how deeply science and society influence perception. Editor: Agreed. It leaves one pondering not only the mechanics of movement, but the implications of that movement within larger systems of power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.