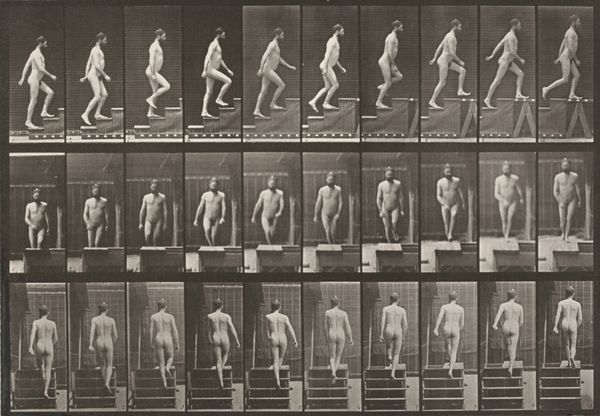

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

action-painting

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

modernism

#

realism

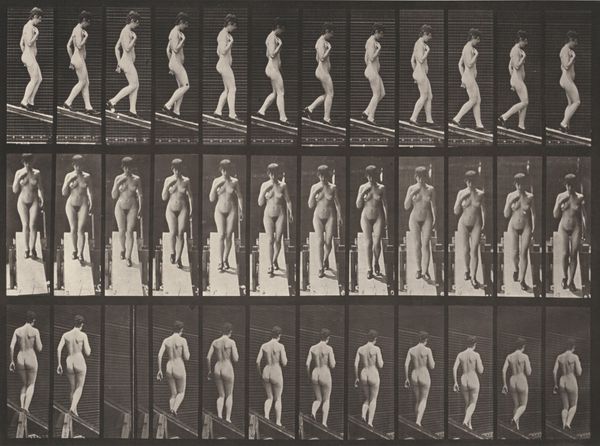

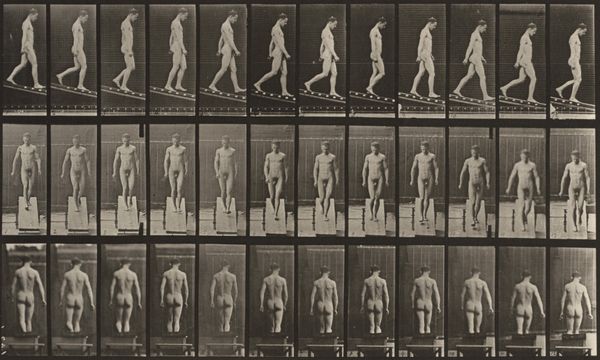

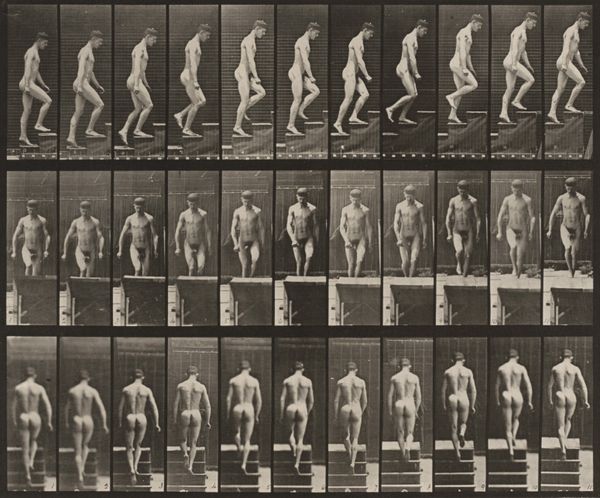

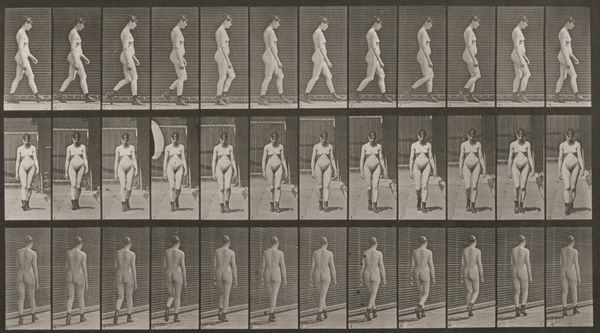

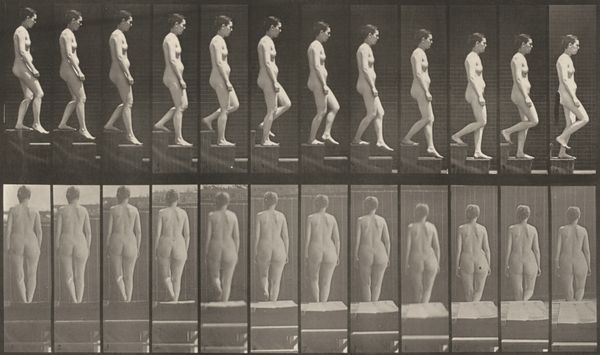

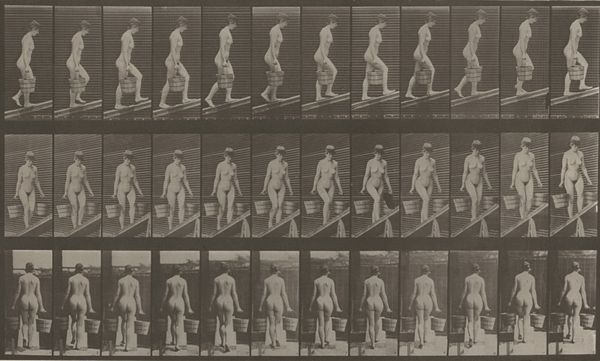

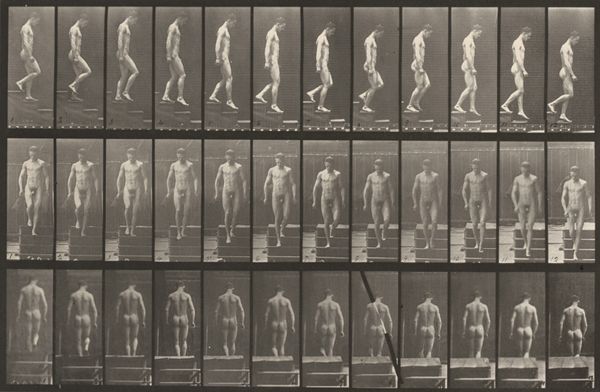

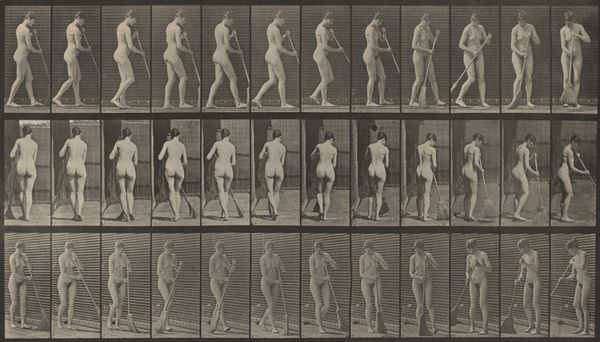

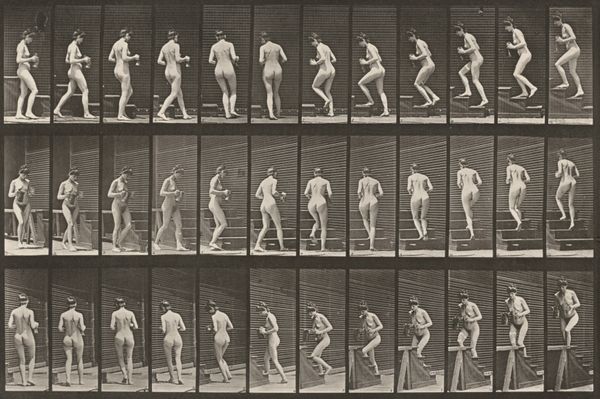

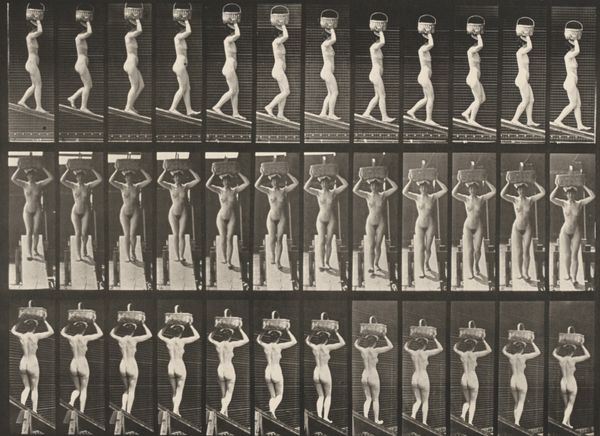

Dimensions: image: 21.25 × 35 cm (8 3/8 × 13 3/4 in.) sheet: 47.6 × 60.2 cm (18 3/4 × 23 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: Okay, so we’re looking at Eadweard Muybridge’s "Plate Number 74. Ascending an incline," a gelatin-silver print from 1887. It's a sequence of images showing a nude man walking up a slope. It feels almost clinical in its depiction, like a scientific study. How do you interpret the significance of Muybridge’s work in its time? Curator: Precisely! You’ve touched upon the core tension of Muybridge’s practice. These images weren’t purely about artistic expression; they were deeply embedded in scientific inquiry and social reform. Remember, this was an era obsessed with scientific positivism, believing that empirical observation could unlock all truths. Muybridge provided "objective" evidence of human movement, initially to settle a bet about whether all four hooves of a horse leave the ground at once during a gallop. What does that initial purpose tell us? Editor: That the artistic value, in this case, wasn't necessarily the point? Curator: Exactly. It became foundational for motion studies in science, yes, but it was shown at art exhibitions! His work played a vital role in shaping visual culture, particularly our understanding of the body, movement, and the power of the photographic image itself. The nudity is also very calculated, not provocative but serving a perceived scientific objectivity, though, of course, never truly neutral. How does the arrangement – the grid – influence your reading? Editor: I see how the grid format emphasizes the analytical nature, breaking down the movement into discrete units and underscoring the scientific intention. It seems Muybridge’s work sits right at the intersection of art, science, and cultural observation, which makes it incredibly compelling. Curator: Precisely, its impact lies in revealing not only how we see but how we understand, categorize, and ultimately, control and disseminate knowledge. It makes you think about the social function of art. Editor: I’ll definitely view Muybridge's work with a much broader historical perspective from now on. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.